Stephen Piccolo and Dr. Robert Crawford, Marriott School of Management

Everyone who invests his or her resources in the stock market wishes to have definitive answers to the following questions:

1) In which stocks should I invest?

2) When should I buy these stocks?

3) When should I sell them?

4) Should I buy and hold my stocks? Or should I actively trade them?

Many financial analysts claim to have solid answers to these common questions. Billions of dollars are spent each year on disseminating financial advice through television, newspaper, trade magazines, and the Internet.

Contrarily, university professors and other theorists have been declaring for decades that reliable answers to these questions do not exist, because the stock market is subject to the “rational markets” theory. This theory states that all available information about a stock is instantly figured into its price, thus eliminating any opportunities for abnormally high returns on investment. Thus, they imply that answers to the above questions are highly elusive.

Countering the credibility of the rational markets theory is the fact that satisfactory answers to other compelling questions, including the following, have not been reached:

1) Why have some investors’ stock portfolios consistently outperformed the market?

2) Does stock-market volatility truly reflect the information available? If so, why are stock prices so volatile?

3) Is there a reliable way to predict future stock-price movements by interpreting historical data?

4) When the Federal Reserve Board reduces interest rates, why don’t stock prices instantly surge?

For this research project, I worked with Dr. Robert Crawford, Managerial Economics professor in the Marriott School of Management, to search for answers to these difficult questions. We studied investment philosophies, technical-analysis methods, and statistical techniques. To do the technical analysis, we obtained historical stock prices for twelve corporations (which have varying longevities as publicly traded entities) and used various techniques to analyze this data.

I have come to believe stock-price volatility is caused not only by information available to investors but also by their psychological reactions to that data and to outside interpretations of it. According to Dr. Crawford, information equals data plus interpretation (i = d + n). Data can be interpreted in numberless ways, and the resulting “information” can also be interpreted in numberless ways. One end result is that investors sometimes have abnormally high amounts of optimism or pessimism, depending on their interpretations. Accordingly, I believe it would be possible for other investors to earn abnormally high returns on investment if they could understand patterns of optimism and pessimism and how these affect market volatility.

The main idea of my technical analysis was to investigate what would happen if investors based their buy/sell decisions on a threshold value that would be triggered as the current stock price deviated significantly from its historical moving average. The idea behind this analysis was that as a stock price deviates unexpectedly from the average, it might be the effect of investors’ overoptimism (signaled by an unexpectedly high price) or over-pessimism (signaled by an unexpectedly low price). Understanding these trends, an investor could make buy/sell decisions and earn abnormally high returns, thus countering the “rational markets” idea.

My hope is that this project will, in some way, serve as a springboard for future analysis, with the eventual result being a better understanding of the psychological phenomena that cause greater-than-expected stock-market volatility and resulting investment opportunities.

Some of the roadblocks I encountered while doing this research were 1) my lack of understanding and experience with terminology and ideas in the financial and statistics sectors, 2) my lack of experience with Microsoft® Excel, and 3) living away from BYU for much of the research time. We had to narrow the scope of the analysis in an effort to keep the research focused. I came to understand the meaning of Thomas Edison’s pronouncement, “I know millions of things that won’t work. I’ve certainly learned a lot.” It was an intriguing experience to let ideas flow, to think freely, and to aim to disprove existing theories.

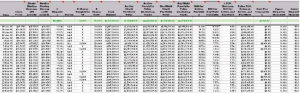

The raw data and calculations are contained in a series of Microsoft® Excel files. I would be pleased to provide a copy of these files to anyone who is interested (email me at pic@byu.net). Thanks to Brigham Young University for giving me an opportunity to have this great learning experience. (Below is a sample of my technical analysis. The print is extremely small, so you will likely need to zoom in to view it well.)