Shaun Odell and Dr. Scott Woodward, Microbiology

In the mid 1980’s archeologists from BYU began excavating a 2000-year-old burial site in Northern Egypt called the Fag-el-Gamous cemetery. This cemetery contains the remains of roughly 350,000 individuals who had been buried there between 200 BC and 400 AD during the Greco-Roman period of Egyptian history. The chemical composition of the desert, as well as the hot, dry climate, naturally mummified not only the individuals of focus, but also numerous textile samples found on the mummies. Excavation of this sight has proceeded from that time, providing unique opportunities for study of ancient Egyptian culture.

This project focuses on the genetic relationships between the members of this ancient community. When analyzed such genetic relationships, compared with specific clothing patterns found at the burial site, would determine to what extent Egyptian textile manufacture was industrialized at this point in its history. More precisely, a large number of the textile samples found on the mummies at the Fag-el-Gamous cemetery bear marked similarities one to another. For instance, several mummies were found buried in clothing that had a distinct star pattern, while others were found wearing clothing with unique color motifs. By studying these individuals genetically, this project set out to determine what insights these textile similarities could provide into ancient-Egyptian life.

Two hypotheses have been suggested to explain these observable textile similarities. The first is that an industrial system existed in which a single or small group of textile manufacturers provided clothing for a significant portion of the community. The second, and more probable explanation is that this was a cottage-based industry in which each family, or group of families, provided for its own textile needs. By amplifying and analyzing individual DNA sequences from the mummies this project proposed to establish familial groupings and find out if textile patterns segregate according to these groups.

This study was performed using tooth, bone and tissue samples that were excavated in 1998 from the aforementioned Fag-el-Gamous cemetery in Northern Egypt. The samples are stored in the Molecular Archeogenetic Research laboratory in the Microbiology Department at BYU. Investigation involved a four-step process: extraction, amplification, sequencing of samples, and analysis of genetic and textile correlation.

The first step was to extract DNA from the mummies. This was accomplished by drilling through the outer layer of excavated tooth or bone samples, in order to retrieve the inner core material that had been naturally preserved within.

After extraction a certain region of the mitochondrial DNA, the D-loop, was amplified by PCR. This method consists of creating an environment in which specific sequences of DNA can be made millions of times in a short time period. The D-loop, or specific region on the mitochondrial DNA that was amplified, was advantageous to this particular study because of a high degree of nucleotide variability, providing a clear means for determining familial relationships.

The final steps were to sequence the DNA fragments, and compare them for similarities and differences. Comparisons between these specific sequences when amplified would reveal whether or not individuals who were found wearing similar textiles were related, or whether they were simply citizens of the same community. If all the individuals that were found wearing a certain type of textile pattern were genetically related, this would indicate a cottage-based industry where each family provided for its own clothing needs. The alternative, that is if the individuals were unrelated, would indicate a community-industrial society in which a single, or limited number of manufacturers provided textile goods for the community.

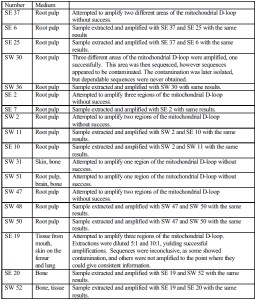

Unfortunately, comparisons between sequenced samples in this study were difficult, as the amplification process often amplified not only the target regions but also unwanted contaminants. On the converse, samples not amplified to a satisfactory level were too weak to allow for dependable comparisons. There were many factors that contributed to these complications. First of all, DNA begins to degrade as soon as an individual dies. In samples as old as the ones used in this project, this degradation leaves a much smaller amount of viable DNA available for amplification. Furthermore, when amplified, normal DNA that hasn’t been degraded is potent enough to drown out minute amounts of contamination that may be present from a variety of sources. In contrast ancient DNA in its degraded state often allows for these miniscule amounts of DNA to be amplified leaving a polluted product. Due to these impediments it was difficult to obtain a clean, viable sequence from these samples. The attached table lists each specific sample studied and the results of work with each.

In conclusion, the answer to the proposed question, whether Egyptians had a cottage- based mercantile system or a community-industrial system, is still unclear. It is evident however that there is DNA locked within these 2000-year-old samples, but a better method is needed for removing and amplifying a clean viable sequence. In April a conference was held and several new methods of extracting DNA from ancient samples were discussed. One possibility discussed is a method of extraction called Isotachophoresis. Isotachophoresis is a process by which DNA can be separated from contaminants and other substances that might inhibit the process of amplification. Work with this possibility has just barely begun, but it is hoped that in the coming months this method, as well as other new procedures, will provide a more conclusive answer to this archaeological unknown.

Table 1: List of Results for each sample studied.

Note-The letters preceding the sample number refer to the quadrant of the burial site from which the sample was excavated (ex. SE 37 means the 37th sample taken from the South- East quadrant of the excavation site).