Charles Thomas Sones and Dr. Chantel P. Thompson, French and Italian

Before arriving in Africa, our contact had arranged for us to work in a village outside of Saint-Louis, Senegal, within walking distance of where we would be studying. We were told that a group of twenty adults and twenty children were already selected who needed literacy skills. Although we were not sure of their specific levels, we were told that most had no literacy skills and many would have no French language skills.

In looking for teaching helps to use in our project, I found very little specific to our needs. I knew that UNESCO had operated similar long term progrmans, but most of their Second language (French or English)literacy programs have been replaced by native language literacy programs. I also contacted UNESCO directly and asked for information concerning programs in West Africa. Unfortunately, two days before our departure, the package arrived from Paris, and had been slit open and all contents were lost. Other sources such as first and second language texts provided small tips and techniques.

We created a series of worksheets for beginning skills. The first was just groups of shapes and symbols to be matched designed to help someone whom had never used a written alphabet to recognize similarities and differences between symbols and letters. One was shapes to be traced and duplicates designed for someone whom had never had any experience with writing tools. Other worksheets were for learning to write the alphabet and numerals. All of these worksheets, instead of lines, were designed with one square inch grey boxes, useful in learning to conform writing to a specific size. There was also a worksheet of blank boxes.

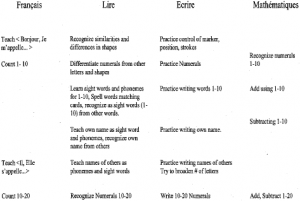

We developed a general lesson plan based on four skills: language, reading, writing, and mathematics. Writing skills involve the motor skills to physically write, not grammatical or literary writing skills. The general lesson plan was designed separating the four skills. While reading was dependent on language, and writing on reading, they were designed so that language skills were not hindered by difficulty in reading or writing skills. It was also designed as an outline of successive subject matter noting specific skills, but not specific activities, leaving each of us to teach however each wished.

In developing the outline for language skills we followed simple contextual plan similar to modern second language program starting with names and numbers, expecting that alone to give us enough context to work on the other skill. As linguistic skills advanced, so could the other skills, including mathematics.

In group meetings before departing, we discussed the conditions of our project, the materials developed, and some general teaching techniques such as Total Physical Response, overcoming language barriers, and culturally transparent classroom activities.

Although we were told that the village was expecting and prepared for us, cultural definitions or those two terms proved to be a major problem. Each time we arrived in the village, we were overwhelmed by masses of children, as many as eight or nine to each one of us. Even though only certain children were supposed to need our help, there was no one who could separate them from the mass of children engulfing us. It was impossible to work outside with these children and if we went into the one room school house, the rest of them crowded windows and the door trying to get in and making far too much noise to work. There was no one to control them and no way to send them away. Village adults avoided us when surrounded by children. and there was no village authority help us with the children. Much to our dismay, many of the children were currently going to school and did not really need our help.

As for the adults, we could not get them to leave the direct vicinity of their huts to come to the school house so we had to break into small groups and work at each individual hut. When we could get them away from cooking, cleaning, napping and tending to children, which was usually about twenty minutes after arriving, if at all, we were able to sit down and work with them. Even then, we were still overcome with children. Eventually, half of the study abroad group would draw the children away from the huts to play games while others worked with the adults. However, the children caught on fast, and it was always a struggle to get any quality time with the adults.

We made several attempts communicate our organizational needs to our contact who made the arrangements with the village. Even though many in our group were unhappy with the program, in their cultural setting, we could not impose our organizational demands.

Overall we did see a great need and an equal desire. Success was limited by time and cultural restraints. If our organizational needs had been better met, or if we had better adapted to the village culture, we could have seen greater results. All said, the entire study abroad group benefitted from the experience, as did the village.