Alisa Paulsen and Dr. Daniel Fairbanks, Botany and Range Sciences

In the Western United States, cheatgrass (Bromus tectorum) is often considered to be an undesirable, invasive weed. When cheatgrass is introduced into an area, it can rapidly establish itself as the dominant species, inhibiting re-establishment of native plants1,2 while competing with important grain crops such as winter wheat.3 Not only does cheatgrass compete vigorously with other vegetation, but because it dies early in the summer, dry sites with high amounts of cheatgrass become susceptible to fires. In addition to threatening ranches, farms, and houses, frequent fires drastically increase mortality of shrubs such as Artemesia tridentata and other important shrub species not accustomed to frequent fire.2 As cheatgrass invades areas, it is accompanied by a fungus (Ustilago sp., a smut) that destroys its seed by harnessing seed production mechanisms and forcing cheatgrass to produce fungal spores instead of seed. This effectively destroys all possible progeny from that individual, as cheatgrass dies after producing seed.

Dr. Susan Meyer and Dr. David Nelson of the Forest Service Shrub Sciences Laboratory are involved in an effort to use the smut as a biological control against cheatgrass. They have found that different inbred lines of cheatgrass are susceptible to different lines of smut (unpublished). This polymorphic susceptibility may explain why whole populations of cheatgrass are not often annihilated by smut epidemics. If one inbred line of cheatgrass dominates a population one year and is wiped out by the corresponding smut, there would be no observable difference in the amount of cheatgrass the following year because the resistant cheatgrass lines would dominate.

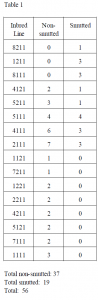

In order to test this theory, we planned to genetically fingerprint individuals collected in 1999 from two populations in the Great Basin (Whiterocks and Hobble Creek) using PCR-based markers developed in 1998-99 (see 1999 ORCA report). We collected 100 smutted plants and 100 non-smutted plants. We fingerprinted 19 smutted and 37 unsmutted individuals from Whiterocks, UT (1999). Unexpected difficulties with PCR delayed completion of the study. We have not completed fingerprinting all the samples from Whiterocks, and no samples from Hobble Creek have been fingerprinted as yet.

The data show a significant difference among smutted and unsmutted plants (see Table 1). We expect to finish fingerprinting the samples from Whiterocks by the end of the year, and we expect the data to support the trend of variation among smutted/unsmutted cheatgrass samples. We may decide to concentrate on further study of Whiterocks alone instead of including Hobble Creek due to the time involved in genetically fingerprinting cheatgrass samples.

References

- Melgoza, G., Nowak, R. S., Tausch, R. J. (1990) Soil water exploitation after fire: competition between Bromus tectorum (cheatgrass) and two native species. Oecologia 83:7-13.

- 2. Young, J. A., Evans, R. A. (1978) Population dynamics after wildfires in sagebrush grasslands. J. Range Mngt. 31:283-289.

- Blackshaw, R. E. (1993) Downy brome (Bromus tectorum) density and relative time of emergence affects interference in winter wheat (Triticum aestivum). Weed Sci. 41:551-556.

Acknowledgments: Dr. Craig Coleman, Department of Botany and Range Sciences, Dr. Susan Meyer, USDA Forest Service Shrub Sciences Laboratory.