Adam Jorgensen and Jonathan J. Wisco, Department of Physiology and Developmental Biology

Introduction

Arrhythmia is a serious heart condition that affects 14 million people in the United Statesi, and is characterized by irregular frequency of atrial and ventricular beats.ii The most serious effects of arrhythmia include sudden cardiac arrest and stroke.iii About 383,000 cases of cardiac arrest are recorded annually in the United States alone.iv In a report complied in 2011 by the World Health Organization, stroke has the second highest death rate of any disease worldwide, ending the lives of 6.1 million people annually.v Recent developments in cardiac ablation have helped in the treatment of arrhythmia by inducing scarring of regions of the heart believed to be propagating the arrhythmic electrical impulses from the cardiac conduction system. By proper use of cardiac ablation, arrhythmia can be corrected.vi Although cardiac ablation has been effective for ameliorating arrhythmia in regions of the heart that are commonly affected, the method could be improved, especially for non-commonly affected regions of the heart, by providing a data-driven, statistical map of cardiac plexus innervation of the myocardium. We propose to produce a three-dimensional map that will greatly improve targeted ablation, and therefore, clinical outcomes. Until now, only rudimentary drawings have been the source of study for cardiologists specializing in this procedure. By properly articulating the intricate nerve branching of the heart, surgeons will be able to better target the specific cardiac plexus fiber territories thus allowing a less invasive procedure.

Methodology

Methodology

We acquired two, pathology-free human cadaveric heart specimens from the from West Virginia University School of Medicine (WVUSOM) Human Gift Registry, and performed high-resolution T2 TSE images (T2 TSE, 0.5×0.6×0.9 mm, TE 73, TR 13290, FOV 320×320) (Figure 1) of the heart specimens. The MRI data was then used to reconstruct a 3D model of the heart using the program Amira.

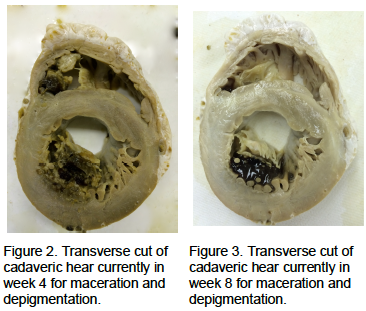

We then started the Sihler’s stain (Figure 2 and Figure 3) to visualize cardiac plexus nerve fibers coursing through the myocardium and completed the first two steps of the staining process.vii

Step 1) Fixation – The harvested specimen is washed with running tap water, then fixed in 10% un- neutralized formalin. The duration of this step depends on the specimen size. Adult human larynx, pharynx, and tongue must be fixed for at least four weeks. The formalin fixing solution may be changed once a week or when it becomes cloudy.

Step 2) Maceration and depigmentation – The fixed specimen is washed under running tap water for about 1 h, then immersed in 3% aqueous potassium hydroxide (KOH) solution adding three drops of 3% v/v hydrogen peroxide to 100 ml 3% w/v KOH solution for depigmentation. The duration of this step varies from several days to several weeks depending on the sample size. For adult human larynx and pharynx, it requires three weeks. The solution should be changed twice a week or whenever it becomes cloudy or dark brown. During this period, the specimen is gradually whitened. The end point of this step is when the specimen becomes translucent and the nerves, especially the small nerve branches, can be seen clearly as white fibers.

Results

The depigmentation stage allowed for more detailed visualization of the cardiac conduction system and depigmentation of the myocardium. In hopes of completing the entire stain and achieving total depigmentation of the myocardium, the structure of the heart began to deteriorate at month 3.

Discussion

This project and the ORCA Grant I received were extremely valuable in enhancing my scientific career. During the past year I was responsible primarily for performing the Sihler’s stain, and working with our colleagues in Engineering to reconstruct the nerve fibers. I worked with other members of my lab for the acquisition of MR images and their reconstructions. I also organized my own team of peers to complete this project. The project grant was used primarily to fund expenses associated with presenting the data we obtained on this and other projects I authored. I presented my findings at the American Association of Anatomists in Boston, MA as well as at the American Association of Clinical Anatomists in Las Vegas, NV. These research conferences helped me develop further plans and develop connections with professors that will prove invaluable in my efforts to become a physician scientist. I have since moved forward in my education and am working on an MD/PhD in Molecular Medicine and Translational Science at Wake Forrest University School of Medicine. Receiving this grant was invaluable in my acceptance and confidence going forward as a scientist.

Conclusion

Sihler’s Stain is an effective methodology for visualizing intramuscular nerve branches. During the depigmentation stage, there is a close line between total translucency and obliteration of the specimen. It is best to move on to the next steps using the Sihler’s solution before total translucency is obtained. We will implement our findings in the next stain attempt.

i Hulen, Tara. “Keeping the Beat.” UAB – UAB Magazine – Keeping the Beat. University of Alabama Birmingham, Dec. 2010. Web. 18 Oct. 2013

ii “Anatomy and Function of the Heart’s Electrical System.” Stanford Hospitals and Clinics. Stanford University, n.d. Web. 21 Oct. 2013.

iii Engstom, Gunnar, MD, PhD, Bo Hedblad, MD, PhD, Steen Juul-Moller, MD,PhD, Patrik Tyden, MD, PhD, and Lars Janzon, MD, PhD. “Cardiac Arrhythmias and Stroke.”Cardiac Arrhythmias and Stroke. Malmo University Hospital, n.d. Web. 18 Oct. 2013.

iv “Why Arrhythmia Matters.” Why Arrhythmia Matters. American Heart Association, 5 Oct. 2012. Web. 21 Oct. 2013. <http://www.heart.org/HEARTORG/Conditions/Arrhythmia/WhyArrhythmiaMatters/Why-Arrhythmia- Matters_UCM_002023_Article.jsp>.

v “The Top 10 Causes of Death.” World Health Organization. World Health Organization, July 2013. Web. 21 Oct. 2013. <http://who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs310/en/>.

vi “Cardiac Ablation.” Mayo Clinic. Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research, 22 June 2011. Web. 21 Oct. 2013. <http://www.mayoclinic.com/health/cardiac-ablation/my00706>.

vii Mu, L., and I. Sanders. “Sihler’s Whole Mount Nerve Staining Technique: A Review.” Biotechnic & Histochemistry 85.1 (2010): 19-42. Print.