Tyler Hammond and Dr. Jeffrey Edwards, Department of Physiology and Developmental Biology

Introduction

Both exercise and stress have an impact on learning and memory. Exercise appears to have positive effects on learning and memory while stress appears to have negative effects on learning and memory. Previous work in our lab has demonstrated that exercise enhances long-term potentiation mediated by electrical stimulus in the hippocampus and that stress decreases longterm potentiation mediated by electrical stimulus in the hippocampus. Long-term potentiation is a measure of the strengthening of the synapses following an electrical stimulus intended to model learning and memory. The hippocampus is the area of the brain commonly deemed responsible for long-term declarative memories.

In addition to long-term potentiation, long-term depression is likely a good measure of learning and memory. Long-term depression is a weakening of the synapses and has been implicated in learning enhancement by “pruning” away unimportant information. Long-term depression can be induced electrically using a low frequency stimulus or chemically using dihydroxyphenylglycine (DHPG), a group 1 metabotropic glutamate receptor agonist.

In the present experiment we measure the effects of exercise and stress on long-term depression in the hippocampus. We use field electrophysiology on the brain slices of mice and measure the field excitatory post synaptic potentials that occur as a result of DHPG-induced long-term depression.

Methods

We used standard C57BL/6 male mice. They were randomly separated into four different treatment groups (exercise with stress, exercise without stress, sedentary with stress, and sedentary without stress). The mice assigned to an exercise group were given free access to a running wheel (mice ran approximately 5 kilometers per day). The mice assigned to a sedentary group were not given access to a running wheel. The mice assigned to a stress group underwent one stressor per day for each of their final three days (5-minute cold water swim, 25-minute stand on elevated platform, 60-minute tail shock in restraining tube).

All mice were sacrificed between days 60 and 100. The brains were extracted, sliced 400 micrometers thick, and placed in oxygenated artificial cerebrospinal fluid. Field electrophysiology experiments were conducted with the stimulating and recording electrodes located in the schaffer collaterals of the hippocampus. Following a 15-minute baseline reading, DHPG was added for a period of 10 minutes. The DHPG was removed and the slices were recorded for an additional 60 minutes. The slopes of the glutamate responses throughout the recordings were calculated using statistical software. The amount of long term depression experienced was compared amongst the treatment groups. Statistical analysis was conducted by one-way ANOVA using the means and standard errors of the treatment groups at time=52 minutes.

Results

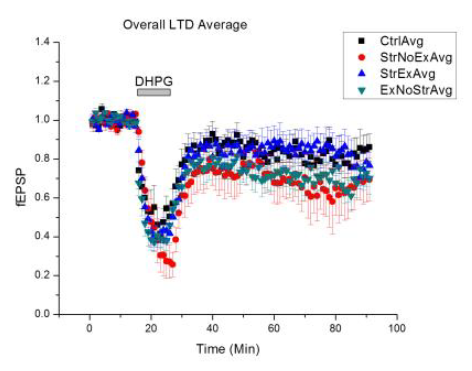

A total of 11 slices were measured from the sedentary without stress group with a mean of 0.87887 of baseline and a standard error of 0.03692. A total of 6 slices were measured from the sedentary with stress group with a mean of 0.77879 of baseline and a standard deviation of 0.06275. A total of 8 slices were measured from the exercise with stress group with a mean of 0.85591 of baseline and a standard error of 0.09357. A total of 14 slices were measured from the exercise without stress group with a mean of 0.77262 of baseline and a standard error of 0.0676. There was not a statistically significant difference between groups as determined by one-way ANOVA (F(3,35) = 0.6607, p = 0.5818).

Discussion

In this experiment, we compared the effects of exercise and stress on DHPG-induced long-term depression in mice. We did not observe a significant difference between the groups. Each group experienced a similar amount of long-term depression following application of DHPG.

These results were surprising to us. We had expected to see a difference between the groups because of previous work which indicated that both exercise and stress have an effect on longterm potentiation. Because long-term potentiation and long-term depression are physiologically related processes, we postulated that exercise and stress would also have an effect on long-term depression. It is possible that stress and exercise could influence long-term depression that is not mediated by metabotropic glutamate receptors. More research should be conducted to determine whether stress and exercise influence other forms of long-term depression, including NMDAreceptor mediated long-term depression.

Conclusion

We conclude that DHPG-induced long-term depression is not directly influenced by levels of physical activity or stress in mice. We acknowledge that there were limitations in this experiment which may have brought us to this conclusion. It is possible that a higher concentration of DHPG would yield different results or that a different exercise or stress protocol could influence longterm depression differently.

Figure 1 – This graph shows the average long-term depression that was experienced by the slices in each of the different treatment groups as a result of DHPG application. DHPG was applied for 10 minutes at time=15 minutes. Experiments were normalized to baseline and field excitatory post synaptic potentials were measured as a proportion of baseline. Error bars represent the standard error.

Figure 1 – This graph shows the average long-term depression that was experienced by the slices in each of the different treatment groups as a result of DHPG application. DHPG was applied for 10 minutes at time=15 minutes. Experiments were normalized to baseline and field excitatory post synaptic potentials were measured as a proportion of baseline. Error bars represent the standard error.