Tristan McKnight and Dr. C. Riley Nelson, Biology Department

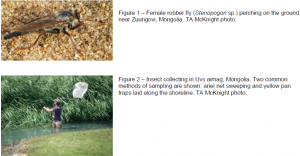

The last few decades have seen an explosion of agricultural expansion and mining in Mongolia. These developments—loosely regulated at best—strain the ecological health of the steppe environment with pollution and overgrazing. Robber flies (Fig. 1) are small predators common in most terrestrial ecosystems that may play an important, yet frequently overlooked role in maintaining balanced insect populations. Unfortunately, very little baseline data exist for evaluating robber fly diversity in Mongolia. Our study set out to provide a comprehensive catalogue of Mongolian robber flies which we hope will assist future efforts to manage and conserve Mongolia’s ecosystems.

My mentor, Dr. Riley Nelson, has already traveled to Mongolia several times to collect insects as a part of the Mongolian Aquatic Insect Survey (MAIS), an NSF-funded inventory of Mongolian insect fauna (grant DEB-0743732). The MAIS expeditions are composed of a diverse collection of researchers from several American and international institutions. Junior scientists-in-training (like me) gain experience from working together in the field with experienced entomologists. This is particularly valuable for the cadre of young Mongolians who work with us to learn the skills they will need to take care of their own country in the coming years.

The 2010 MAIS expedition lasted for one month, from late June to late July. We spent three weeks in the field and one week in the MAIS laboratory in the capital, Ulaanbaatar. Our field operations were conducted in the northwestern corner of Mongolia, around the Kharkhiraa mountains and Uvs lake. Every day we drove from stream to stream in Russian trucks and jeeps, trying to sample two to four different sites and re-pitching our tent camp each night at our last site. I focused on collecting robber flies and other Diptera (true flies) with ariel net sweeping, and was also responsible for running the yellow pan trap biodiversity sampling. (Fig. 2) Specimens were stored either in vials of alcohol or pinned and dried in boxes.

Each year for almost two decades, the MAIS expeditions have returned from the field with thousands upon thousands of specimens. These must all be accurately sorted, labeled, and identified if they are to be useful for analyses of biodiversity health and species distributions. To help us compile and manage these data in concert with the other MAIS sponsor institutions, we maintain a computer database designed by Sarah W. Judson, a former graduate student of Dr. Nelson. Over the last year, Ms. Judson has taught me to manage this database and input the collection information from this year’s expedition. Since then, I have been working with the other students in our lab to label and curate our specimens.

With the basic curation responsibilities taken care of, we have been able to move on to identifying the specimens we collected. To help us know what species to anticipate and which identification keys to obtain, I compiled the first truly comprehensive species list for Mongolian Asilidae. To do this, I had to search out all publications from previous expeditions to Mongolia,

comb through them to learn if they collected any robber flies, and then read through species synonymies to see whether these reported taxa were still valid names. This work all required translating from the original Russian, German and Czech. In the end, there proved to be 105 known species in 38 genera of robber flies indigenous to Mongolia.

I have only identified about a dozen species to date, but this work is currently ongoing and will increase greatly in the coming month. We are already beginning to find noteworthy results, including the first male ever collected for Cyrtopogon rufotarsus, and range expansions of over a thousand miles for certain other species.

While the scientific goals of this project are so far still unfinished, this project has already born significant fruit by training me in my planned career of field entomology. I have learned how to find and collect many different types of insects, and have been able to devote focused study on the habits and distributions of the robber flies. I have learned important curation and identification skills, and have been able to practice creating and executing research plans.