Lonnie Ikaika Bullock and Dr. Kristie Seawright, Business Management

Introduction

The purpose of this project was (1) to conduct exploratory research on the flows of money within supply chains, including aid chains that exist in poverty environments, and (2) to identify the potential of money flows to mask inefficiencies in the supply chain that can threaten enterprise viability.

Though the flow of goods and information are widely discussed in the Supply Chain literature, only a few have contributed to the academic research on the flow of money associated with supply chains. This continuing exploratory research studied the economic flows of money in supply chains. Particularly, the correlation between economic subsides in the supply chain and their effects on a supply chain’s sustainability. The following research questions were addressed:

RQ1: What are the characteristics of the flow of money in the supply chain?

RQ2: What are the effects of subsidies on the supply chain?

RQ3: Do subsidies mask inefficiencies and promote unsustainable practices?

Methodology

Originally the project was going to map out the supply chains of small enterprises gathered in pervious research. From discussion with my mentor and other researchers it became apparent that nothing was known about any research that has been done on the flow of money. With out a foundation analysis of the supply chain maps would prove difficult. Through analysis of academic journals formal economy examples were found. The themes and trending topics found through the accumulation of relevant works were then analyzed. These analyses then lead to new areas and topics to research. To find answers to the research questions journal articles that gave specific industry examples were primarily sought after to see if the hypotheses in research question three was supported.

Results

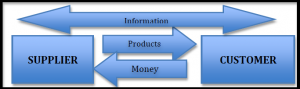

The direction of the three main flows in the supply chain was supported from the research findings. The flow of products move from supplier to customer, the flow of information flows is bilateral between supplier and customer and new research has shown that the flow of money goes from customer to supplier in exchange for goods and services.

Discussion

The researched centered on two industry examples of subsidies being used. The first being production of Bio fuels with specific examples from the production of bio diesel in Brazil. The second looked at the global fertilizer supply chain, focused on distribution in Africa.

Case 1:

Bio Fuels Bio fuels are an emerging solution for the present-‐day concerns about rising oil prices and depletion of crude oil resources the world over. Biodiesel is produced from combining vegetable oils, animal fats and other renewable resources with methanol or ethanol. The results are similar to petroleum-‐based diesel fuel. The application of biodiesel is similar to traditional diesel though chemically a much more sustainable source of fuel for commercial application. The supply chain has three main processes: supply, production, and distribution.

In this case it was found that the government provides subsidies that cover over 20% of the costs of production and distribution. The current bio fuel supply chain is not sustainable because they are 20% more expensive then traditional petroleum fuels and with out the government subsidies would not be able to compete in the market. The subsidies also support local education in R&D projects and local farmers of the raw materials. To make this a sustainable product are the subsidies in fact masking inefficiencies through out the supply chain because they are able to compete with out further development at this time?

Case 2:

Global fertilizer industry For the global supply chain of fertilizer suppliers 50-‐60% of them are concentrated in 5 countries. This places a majority of the market power with them and creates prices that are too high for developing areas that need the fertilizer to support their agricultural capabilities. This study found that a 10% increase in competition could increase fertilizer use by 13–19% and rural incomes by 1–2% in regions like sub-‐Saharan Africa. Overall, the results highlight the need to further examine the pricing behavior and potential market power exertion of major global producers, which can help to better understand the industry supply chain in developing countries and provide additional insights into the design of policies, including input subsidy programs, intended to promote long-‐term fertilizer adoption.

The use of subsidies would allow new suppliers to enter the market and compete with the large global manufactures and increase the economic sustainability of those in the agricultural supply chain. But will these new manufactures be able to gain production levels of a global standard with the subsidies continuing into the future?

Conclusion

This research established the foundation to now analyze the small enterprise database and map the flow of money. With these formal economy examples we now have a bases to compare to. This research has shown that subsides have indeed enabled inefficient practices that impact the sustainability of the supply chains. These findings will support professor Seawright’s continuing research and will be a part of the paper submitted for peer review and publication summer 2014.