Danielle Peterson and Dr. David Kooyman, Physiology and Developmental Biology

Our bodies are dynamic structures that do not operate as individual compartments, but as a whole. When something goes awry in one specific tissue or organ, specific signals from that diseased area are released affect other tissues. I received an ORCA grant last year to study my hypothesis that degradation of Osteoarthritis (OA) is primarily associated with a systemic immune response to trauma of articular cartilage. In order to verify this hypothesis, a treatment that creates OA in one localized area while other tissues remained undamaged was needed. The OA genetic mutant mice that researchers normally turn to couldn’t be used for this project because they result in defects in cartilage in all regions of the body, making it difficult to see if defect is a result of immune response or defective building materials for cartilage.

The destabilization of the medial meniscus (DMM) is a surgical technique performed on mice that allows an individual to induce a traumatic response in one localized area leaving other areas, initially, unaffected. Performed on the right knee, the medial mensicotibial ligament is cut, causing the medial meniscus to slip out from between the tibia and femur, causing the two bones to articulate with one another and develop OA at an accelerated rate. I predicted that as a result of the trauma induced in the knee, OA would develop in the temporomadibular joint of the jaw, an area completely isolated from the knee, as the mice aged, indicating a systemic immune response tied to the development of Osteoarthritis systemically.

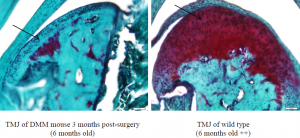

Mice were euthanized at 4, 6, 8 weeks post-surgery.Tissues were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde, processed to paraffin sections, stained with Hemotoxylin, Safranin O and Fast Green. The tissues were sectioned into 6 micrometers thick and analyzed using light microscopy using Mankin Scoring, a technique used to score the degree of Osteoarthritis based on visual indications in the Safrin O, Fast Green staining. Mice that underwent the DMM procedure demonstrated signs of Osteoarthritis in both knee and temporomandibular joints.

The table below is an example of Safrin O and Fast Green staining of a section of a temporomandibular joint. The image on the left is of a mouse that underwent knee surgery. Note the decreased size of the articular joint and lack of proteoglycan staining (depicted in red). On the right is a healthy, wild type mouse of the same age. The vibrant red indicates a higher level of proteoglycans (proteins that allow cartilage to withstand compression forces). Another interesting observation is the morphology of chondrocyte within the cartilage (The chondrocyte indicated by an arrow on the left lacks a pericellular matrix and is decreased in size with fewer chondrocytes. However, the chondrocyte in the healthy tissue has a noticeable pericelluar matrix (lighter red region surround the cell) and there is a general abundance of cells in the tissue. The mice that underwent the surgical procedure demonstrated signs of Osteoarthritis in the knee and temporomandibular joint.

While we have identified that inducing OA in the knee results in its development in unrelated tissues, the mechanism behind this response is still unknown. Further research is being done on my part to study the effects of cellular receptors involved with the development of OA.

Result of this study and other procedures were presented in a poster at the Osteoarthritis Research Society International (OARSI) Conference in San Diego, California, September 14-17, 2001 and published in Osteoarthritis and Cartilage Vol 19 (Suppl 1): S62.