Matthew Butler and Professor Brian Capt, School of Technology

Perhaps the greatest challenge to this project was determining which materials to use in the construction of the modules. There are a multitude of materials that could have been used for the project, many of which might have worked well for the designated use. The shelters have a specific set of criteria that required several different properties that the material had to fill, including: (a) price—it needed to be fairly inexpensive to purchase and ship to a shipping container assembly area, (b) durability—the panels that make up the module must be made from a material that can support itself, the roof members, and resist severe wind loads from potential hurricanes or cyclones, and (c) easy of assembly—conventional hand tools must allow for the assembly of the units without the need of auxiliary power or significant training, also the panels should be light enough for one or two people to fairly easily move them.

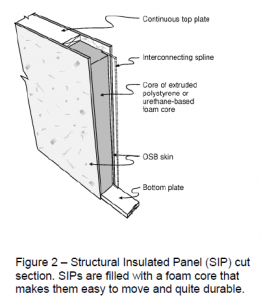

Choosing what material system even proved to be a significant challenge. My professor recommended working with Structural Insulated Panels (SIPs) and that became a good starting point. Through networking with SIP manufacturers I was able to discover other methods of panelized construction that might be suitable for the project. Discussion also ensued over whether or not a panelized system was even the best solution for the problem, as a graduate student friend worked with concrete domes and another solution with a steel framework was also a good possibility.

Through my research among construction product manufacturers I discovered that at least one other group had already designed and manufactured shelters to fill the need that my project attempted to fill. The manufacturing group, a for-profit corporation based in Idaho, built prefabricated 500 square foot structures complete with solar panels, kitchens, and a multitude of other amenities. Because of the significant provision for amenities, each unit cost approximately $40,000 to produce and build, which is a very significant cost for shelters that are designed to be temporary. This directed my research to create a very basic structure without amenities other than basic shelter to reduce costs and focus on the core need: basic shelter.

Since our design is a modular approach, additional modules can be designed to fill different needs. For now the design has been focused on the bare need for shelter; providing a place for victims of disaster to sleep and live away from the elements. Future additions for this project would include additional designs for a kitchen module, a bathroom module, and a laundry module that would be used communally. Some of our design process included discussion of how to enable the transformation of a temporary dwelling into a permanent one if needed. Further future designs could determine an effective master plan for dozens of modules, including locations for the specialized modules.

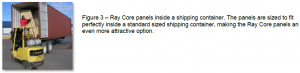

After much deliberation and research, the decision was made to go with a specialized panel approach, but to not use traditional SIPs. SIPs are a great product but have exposed wood panels that would require several layers of additional weather protection for places that experience frequent precipitation. To minimize specialized labor and to ship as close to a finished product as possible, Ray Core brand panels were chosen as the specified panel technology.

Ray Core panels feature a 2×4 premade panel that comes in large 4’ sections but already have moisture barriers attached to the panels, meaning that very little needed to be done for additional weather protection. Additionally, the Ray Core factory is capable of attaching other materials to the panels as needed to customize as needed, further reducing labor costs and extra assembly on site. Reducing on site assembly was an enormous factor in choosing a product for the modules, so Ray Core’s factory capacity was a major consideration.

Thanks to labor saving materials, minimalist design, wall sharing between modules, and other factors, we estimate that a per unit cost for a 144 square foot temporary dwelling should be around $5500. This is a mere fraction of the cost for the larger units that the Idaho company had built in Japan after the tsunami.

However, while the design is done, there are some finishing touches that will be completed January 2012. Two engineering details need to be approved and a few peripheral items to be included in the module need to be finalized for the final costing summary. Once completed, there will be enough done to start new design for master planning a community layout and determining the best way to convert the modules to a permanent dwelling.