Lori Rasmussen and Dr. Mary Stovall Richards, History

The rhetoric of the Mexican-American War, and indeed, the entire expansionist era, claimed that the United States had a God-given responsibility to spread their white, Protestant, capitalistic, and democratic civilization to the heathen of the world. Though sometimes implied, and sometimes explicit, the notion included the idea of educating the barbarians who held a tenuous grasp on the land. Education in this sense meant indoctrination into American culture, including the English language, high literacy rates, gender roles, and a multitude of other facets.1 During the middle part of the nineteenth century, Northern states moved rapidly toward a truly literate society, while other areas of the country, the education of the masses remained far less hopeful. In the newly acquired territories from Mexico, the populace struggled with a transition to American ways of life, government, and language. Statistics on women’s literacy rates under the Mexican rule are extremely nebulous, but had the United States fulfilled the culturally imperialist promises made in the theory of Manifest Destiny, the women of an up and coming city like Albuquerque, New Mexico, could have expected a significant, if not rapid, improvement in their educational level. Like many of the other promises implicit in American ideals, however, the level of women’s education floundered in the face of economic upheaval and Anglo-Saxon disregard.

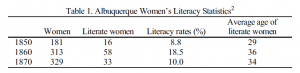

The accuracy of the literacy statistics from the census is doubtful for a number of reasons, including the dual language confusion and the uncertain level of ability implied by the term “literate.” However, the census remains the best extant source for calculation the level of women’s literacy. Statistics for women’s literacy under the Mexican regime are unfortunately not available, but as the area was not organized into a territory until the Compromise of 1850 it is presumable that literacy rates in that year reflect the Mexican system of education.

As can be seen in the previous graph, women’s literacy rates did rise in the first decade of the American regime by almost ten percent, but contrary to expectation, in the 1860’s education did not just stagnate, but actually took a step backwards. It is important to note that the racial and birthplace data indicate that the changes are only partially due to an influx of American women educated in the East. Even the early progress, however, the percentages were sadly below those given in other parts of the country. One study found that in Northern states in 1860, ninety-four percent of white married women were literate. Estimates of the Southern states are lower, hovering in the mid-eighties, but still are substantially higher than those of New Mexico.3

Other methods of determining literacy rates include a study of the use of signatures (as opposed to signing with X’s or having someone else sign in lieu of the person contracting the agreement). Unfortunately for studies in nineteenth century women’s history, most women were not involved in the activities that produce extant documents with signatures. In the Twitchell Archives, what little information on women exists was written by their male counterparts. The presence of books and newspapers also indicates a certain level of literacy among the populace. A study of wills, American accounts, and Mexican government documents reveals that books were extremely rare prior to the American influx of both trade and immigration. The Rio Abajo Weekly Press of Albuquerque generally conveys the impression that no women existed in the area. When by chance they are mentioned, it usually takes the form of a man writing an editorial on the myriad of virtues he expects in a wife or advice. A random selection of advertisements found them to appeal primarily to men. The final method used to determine literacy was another study of the census which indicated which children had attended school within the previous year. Again, the numbers were sadly behind the rest of the country, both at the beginning and the end of the period under study. In 1850 only 1.3% of the girls between four and twenty years were in school. In 1860, that number rose only to 6.4%, and in 1870, it dropped to an absolute zero percent. For boys, the numbers involved are higher, but the trends remain the same.4 Perhaps even more telling is the fact that many prominent Americans sent their children out of the territory for their education.

Wealth, of course, has a profound effect on literacy. Further analysis of the census indicated that literacy did not necessarily change a woman’s ability to own her own property, but that the wealth of the household did greatly increased the likelihood of the daughters to learn to read.

The reasons for the failure of the ideals of Manifest Destiny are difficult to pin down. Certainly part of the problem stemmed from American unwillingness to invest in their new acquisition when Texas and California seemed so much more promising. In the 1860’s New Mexico not only shared in the nation-wide tragedy of the Civil War and its aftermath, but also a series of economic strains from heavy frosts, torrential rain and hail, spring floods, grasshoppers, and cornworms. In addition, they continued to lose livestock and security to the ongoing struggles with several tribes of Native Americans. Whatever role each of these factors played, however, it is clear that American dedication to their own educational ideals did not survive in New Mexico’s climate.

___________________________________

1 Ray Allen Billington, The Far Western Frontier, 1830-1860 (New York: Harper & Brothers, Publishers, 1956), 148-150.

2 The United States Federal Census, 1850, 1860, 1870.

3 The United States Federal Census, 1850, 1860, 1870; Lee Soltow & Edward Stevens, The Rise of Literacy & the Common School in the United States: A Socioeconomic Analysis to 1870 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1981), 158. The Northern and Southern women’s statistics are based on white married women.

4 The United States Federal Census, 1850, 1860, 1870.