Michael Packer and Dr. Mary Stovall Richards, History

During the Civil War disease was a major problem. Many different diseases combined to cause immense problems for civilians and army personnel alike. More soldiers died from disease than from battle. While medical knowledge was growing, physicians had neither the knowledge nor the understanding to combat most diseases. Doctors both North and South had little success against many illnesses.

Early in the war the Union occupied two major Confederate cities: New Orleans, Louisiana, and Nashville, Tennessee. In these two occupied cities, specific diseases became significant threats to the Union’s soldiers. In Nashville a growing problem with venereal disease was inundating army physicians. This was the result of the large number of prostitutes that saw the large numbers of soldiers stationed there as an excellent source of income. In New Orleans yellow fever had been a problem for decades. Southerners predicted that it would wipe out the Union army stationed there, since they were unaccustomed to the climate and diseases of the South. Northern leaders tended to agree with this prediction. Both yellow fever and venereal disease also affected other parts of the country, but they were perceived as a more concentrated and significant threat in the cities in question.

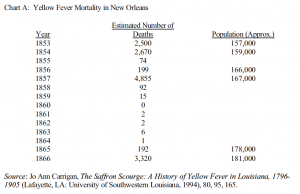

Despite the problems and predictions, history records that both diseases had minimal impact on the Union army during the occupation of the fore-mentioned cities. Chart A illustrates how yellow fever was essentially non-existent during the wartime occupation. These were greatly unexpected results. They were magnified by the fact that the diseases returned to the respective cities after the war, as can also be seen in Chart A.

The purpose of my research was to investigate these unusual results, determine their causes, and identify the reasons that the diseases were not controlled after the war. I did this by researching primary documents such as diaries, memoirs, statistical reports, and where possible, newspapers. I also searched secondary sources; however these specific events have received minimal attention in most Civil War records.

I discovered that because the threat in these cities was so clear, Union leaders took control of some of the cities’ sanitary programs. In Nashville the army initiated a licensing system for the prostitutes. They were required to register with the army and have weekly physicals. Only prostitutes free of venereal disease were given a license. The program was a success and greatly reduced the number of cases of venereal disease among the soldiers. In New Orleans the army took control of the entire sanitary system. There was a debate as to the exact source of yellow fever, and because of this multiple measures were taken. The Union cleaned the city extensively and established a strict quarantine for ships entering the city. To most people’s surprise, yellow fever did not threaten the city for the entire war, but returned soon after the war was over.

My conclusion to the research was that only the rigid authoritarian power of the occupying army was strong enough to implement the measures necessary to curb the diseases. While democracy is a preferable form of government, a more rigid and powerful leadership can result in very positive outcomes, as illustrated here. In Nashville and New Orleans the military commanders were successful because they saw the biological threat as a high priority and imminent threat, and had the power to immediately act upon that threat. The local municipalities and citizens did not perceive the diseases to be as significant as the Union Army had, and they lacked the resources to maintain the rigorous programs. The specific measures that obtained results were discontinued soon after the war for those reasons, leading to the diseases’ return. Furthermore, the successes of the military in New Orleans were not the result of their understanding of the disease. Even after the war, little if anything was learned about the nature and sources of yellow fever. Venereal disease was familiar to the physicians of the time, and the army acted accordingly, but yellow fever was something of a mystery. Despite the remarkable results during the war, doctors record virtually no advancements in their understanding of the disease, and it continued to plague the South until the turn of the century.

The only significant problem in my research was a scheduling problem that prevented me from traveling to the areas in question to access newspaper archives that would have greatly improved my information. Because of the internet and digital archives, this did not entirely hamper my ability to access pertinent primary sources. This research project was successfully defended and was the culmination of my graduation with university honors.