Joseph B. Hill and Dr. Michael D. Phillips, Humanities, Classics and Comparative Literature

In much of West Africa, the griot is the central figure in the performing arts. Traditionally, only those born into the griot caste perform publicly in any capacity, be it in music, dance, historical recitation, public speaking, or jesting. Although other castes look down on such work, griots embrace it and carefully guard their monopoly. Immune to most social sanctions, griots speak good and bad with impunity, and nobles pay dearly to ensure that griots say only good (1).

I spent the first half of 1998 in Senegal and other West African countries seeking to answer several questions. First, how are griots’ current artistic activities consistent or inconsistent with their traditional ones? How much monopoly do griots maintain in performance? What has perpetuated this monopoly and what has challenged it? Although Senegal will probably always have its griots, several factors are threatening their prominence. I found modern education and economic situations to be the most significant challenges to the griot monopoly.

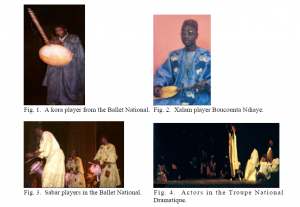

The first four months of my research centered in Dakar, Senegal’s most non-traditional setting and home to its highest concentration of modern artistic activity. There, I learned three griot instruments: the kora (21-stringed harp, Fig. 1), the xalam (five-stringed lute, Fig. 2), and the sabar (Wolof drum, Fig. 3). Concerts, plays, and dance performances showed me how urban griots adapt traditions. After my stay in Dakar, a rural griot family hosted me and showed me a more traditional lifestyle. Classes and discussions at the national arts schools in Dakar and Bamako showed me how instructors institute and teach the griots’ art to non-griots.

Modern economic institutions have largely eroded Senegal’s patron/client caste system. Before colonialism, an entourage of slaves and artisans provided noble landowners with their wealth in exchange for food and housing. While the artisan castes have developed trades to replace symbiotic gift-giving, griots cannot set up word and song in workshops. Consequently, griots continue more than the others to solicit gifts from patrons, even if they no longer practice the griot’s art. Their reputation of incessant begging has worsened.

Although modern-minded Senegalese insist that caste no longer matters, griots still dominate all major performance occupations in Senegal. They most conspicuously dominate music. Griot singers monopolize the music-video spots on national television and radio. Of the dozens of musicians I encountered who played traditional instruments professionally, only one was a non-griot, and his instrument functions more as a Western instrument in his bebop group.

Why does liberal thinking not make musicianship a common possession? Lack of effective artistic education is largely responsible. Griots are immersed in their instruments from infancy, whereas students in a modern classroom have short lessons that require a concentrated and structured method. Senegalese music schools have no such methods to pass traditional music on to nontraditional players. Almost all traditional music teachers at the Conservatoire National are griots, and almost all their students are non-griots. Yet I never knew of a student there who had mastered an instrument. Unable to buy instruments, students must share the few battered ones the school can afford. After four years of irrelevant sight-reading courses and weekly instrumental classes in which they rarely touch an instrument, students leap into the music market to compete with born musicians. Access is more equal to Western instruments, which are prohibitively expensive to griots and non-griots alike. The conservatory may someday challenge griots’ monopoly in singing: its traditional vocal ensemble trains some talented singer-composers. Singing does not require expensive instruments or individual lessons.

Lack of education has endangered Senegalese “classical” music, or the music of royal court griots. Griot school children miss the constant musical exposure their parents had. Great masters such as xalam player Samba Diabaré Samb and kora player Lalo Kéba Dramé have no successors, and young griot instrumentalists often have a superficial knowledge of their instruments. Modern schools fail to pick up where tradition left off.

Senegal has no long-standing tradition of stage theater, but when the colonial French hosted theater competitions and independent Senegal established its national theater, griots naturally rose to the occasion. Only they had experience speaking before groups, telling stories, and role-playing. Griots still dominate the national dramatic troupe and many other troupes around the country (Fig. 4). But non-griots are infiltrating the dramatic world much more than they are music. Like singing, drama can be taught in groups and without materials. Several well known troupes in Dakar, such as “Les Sept Kouss” and “Les Gueules Tapées,” are made up of conservatory alumni. Some alumni have replaced griots in the national troupe, the most notoriously griot-dominated troupe of all.

Griot orators and historians also dominate Senegalese broadcasting. Of the four principal television announcers, only one is a non-griot. These four (El Hadj Mansour Mbaye, Moustapha Ndiaye, Abdoulaye Mbaye Pekh, and non-griot Oumar Dia) announce the news, commentate traditional wrestling, and frequently speak at community events. El Hadj Mada Seck, drum major of former President Léopold Senghor, is now a prominent evening radio announcer. As in music and drama, education is possibly the greatest agent of change in broadcasting. The Centre d’Etudes, des Sciences, et des Techniques de l’Information, a branch of the University of Senegal, trains young announcers to replace the aging griots. Whereas the older griot announcers dress in traditional robes and speak Wolof in all their programs, the younger non-griots wear European fashions, speak French, and work separate programs. Wherever non-griots replace griots in broadcasting and the arts, they tend to bring a more modern style.

Although changes in economics and education are diminishing the griot’s importance in many areas, griots alone still exercise many traditional functions. Every important celebration, political rally, or other large gathering requires a group of griots to entertain, speak for the family, act as intermediaries, and flatter and beg from all present. Even modernized city dwellers have their griots, although their griots almost always come from the village of their patrons’ history and not from Dakar. The traditional art of the griot will never again be intact, but griots as an important part of Senegalese culture are far from dying out.

References

- Sory Camara. 1992. Gens de la parole: Essai sur la condition et le rôle des griots dans la société malinké. Karthala, Paris