John R Dayton and Dr. Donovan E Fleming, Neuroscience Center

A unique aspect of soccer is the use of the player’s head to direct the ball. Participants can “head” the ball to score a goal, pass to a teammate or gain control of possession. Studies performed on soccer players at the international2,5,7,10,12 and Olympic1 levels have shown memory2,3,4,6,8,9,10,12, attention3,6,11,12, concentration2,3,6,11,12, and judgment24 deficits. Is such damage due to practice schedule and necessitated drills, or is it the cumulative result of lifelong soccer participation? If due to lifelong participation, are high school participants at risk?

The purpose of this study was to determine if evidence of cognitive damage exists among high school soccer participants. Since memory is the most diagnosed form of cognitive damage among professional soccer athletes, I elected to administer memory tests to high school soccer participants. My control group consisted of 32 male and 32 female students from Mountain View High School (ages 15-18), and my experimental group was made up of 38 males from the Mountain View and Orem High School varsity soccer teams, and 26 females from two competition soccer teams (ages 14-18).

To test visual and verbal memory, the Rey Complex Figure (RCFT) and Rey Verbal Learning (RVLT) tests were used. First, the subjects were shown a complex figure and asked to copy it onto their paper. As a distraction, a survey was then administered to obtain relevant demographic information. After this five-minute delay, the participants were asked to draw the complex figure from memory, thus exhibiting immediate visual memory. Verbal memory was next tested using the RVLT. For this test, a list of the same 15 words was presented in five consecutive trials and the participants wrote, after each trial, as many words as they could remember. A second 15- word list, acting as an interference, was then administered. Next, delayed visual memory was tested as the participants were asked to draw the complex figure from memory after a 30-minute delay. The participants were then asked to recall the original set of fifteen words. Finally, the participants were given a paragraph and asked to circle words they recognized from the first list.

Several aspects concerning the construction of this study must be addressed: One concern about the test administration was that it was administered to large groups with a co-facilitator, as opposed to being administered in the standardized and normed one-on-one procedure. To compensate for this non-standard administration, participants sat separately and placed each individual trial in an envelope as it was completed. In recruiting athletes, several coaches would not allow their athletes to participate in the study, one citing that he didn’t want to ‘make soccer look bad.’ Another concern was a grade point average (GPA) disparity, because both male and female soccer players had higher averages than the non-soccer participants. The male’s average was .38 higher and the female’s average was .3 higher.

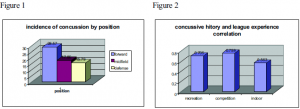

The soccer participants performed better on the battery than the non-soccer participants; however this may be a result of the GPA difference. Among soccer players, there was a significant correlation between field position and concussive history (r = .841) (see figure 1). It is hypothesized that Forwards are more at risk for damage because they compete with Defenders and Goalkeepers to head the ball. There is also a correlation between the number of seasons played and the number of concussions received; more participation leads to more risk for injury. It is hypothesized the incidence of concussions is lower in indoor soccer (r = .563) than recreation (r = .705) and competition (.759) soccer because indoor goals are smaller and lower to the ground, making scoring by heading less frequent. Indoor soccer also concentrates less on heading skill and more on foot pass and possession skill. This study reinforced two previous findings: the first being that male participants are more likely to suffer concussions than female participants (r =.968). Additionally, female participants performed better than their male counterparts on the verbal tests.

This study was constructed as a pilot study analyzing only a sample of the population. It is this author’s recommendation that a longitudinal study be conducted looking at large populations of soccer participants and the change in their memory from ages 12 to 25. Because of time constraints, I was only able to perform a sample test of the local high school soccer population.

References:

- Asken MJ, Schwartz RC: Heading the Ball in Soccer: What’s the Risk of Brain Injury? Phys Sportsmed 1998;26(11):37-44.

- Baroff GS: Is Heading a Soccer Ball Injurious to Brain Function? Journal of Head Trauma Rehabilitation 1998;13(2):45-52.

- Bruzzone E, Cocito L, Pisani R: Intracranial Delayed Epidural Hematoma in a Soccer Player. American Journal of Sports Medicine (Am J Sports Med) 2000;28(6): 901-903.

- Christensen D: Heading for Injury. Science News 1999;156(22):348-349.

- Grote C, Donders J: Brain Injury in Amateur Soccer Players. JAMA 1992;112(10):1268-1271.

- Injuries in Youth Soccer: A Subject Review. Pediatrics 2000;105(3):659-661.

- Jordan SE, Green GA: Acute and Chronic Brain Injury in United States National Team Soccer Players. Am J Sports Med 1996;24(2):205-210.

- Kent H: Ball Rolling on Research into Heading Injuries. Canadian Medical Association Journal 1999;161(11):1434.

- Matser EJ: Neuropsychological Impairment in Amateur Soccer Players. JAMA 1999;282(10):989-991.

- Matser JT. Chronic Traumatic Brain Injury in Professional Soccer Players. Neurology 1998;51(3):791-796.

- The Harm of Heading in Soccer. Phys Sportsmed 1995:23(11):16.

- Tysvaer AT, Lochen EA. Soccer Injuries to the Brain. A Neuropsychologic Study of Former Soccer Players. Am J Sports Med 1991;19(1):56-60. 28.57 17.86 15.79 0 5 10 15 20 25 30 1 position incidence of concussion by position forward midfield defense