Scott Zogg and Dr. Kay Smith, Psychology

With the help of the BYU ORCA scholarship provided, professors in the Psychology, Statistics, and Sociology departments, and the use of a 13 console CATI-system tele-lab on campus, behavioral science and statistics students completed a representative survey of Provo adults for the Provo Police Department. The survey, which interviewed 449 respondents at a 62% response rate, was designed with many interests in mind. The following is an adaptation about crime victimization questions from the final report.

Crime victimization is a difficult occurrence to measure. It requires the trust, memory, and honesty of the respondent. Additionally, it requires the ability of victims to recognize their victimization and classify themselves accordingly. To probe the validity of victimization rates as commonly measured, this survey contained a second victimization component which contained 5 behavior-specific questions. These questions were designed to overlap manifestations of vandalism, assault, or sexual assault. It was not supposed that they would be comprehensive. Rather, their purpose was to uncover incidents of crime which the official classifications did not reveal. The official crime category questions were asked in the following manner:

I will now read a list of crimes. After each crime, please answer “Yes” if you have been a victim of that crime in the last three months or “No ” if you have not. Vandalism? (Response), Motor Vehicle Theft? (Response), Burglary? (Response), Robbery? (Response), Any other stolen property? (Response), Assault? (Response), Sexual assault, rape, or attempted rape? (response). Respondents who answered “Yes” to any of the victimizations were then asked about the number of times, whether they knew the person who had committed the crime(s) and whether they reported the crime(s).

The five behavior-specific questions proceeded immediately after the official category questions in the following manner: I will now read a list of more specific events which may have happened to you. Please answer ‘Yes’ after each event which has happened to you in the past three months or ‘No’ if it has not. Someone has spray-painted graffiti on something you own. (Response) Someone has broken a window in your car or home. (Response) Someone has physically attacked you. (Response) Someone has forced sexual contact with you without your consent. (Response) Someone has punched or slapped you. (Response) If a respondent answered yes to any of the above questions, they were then asked whether they considered the event to have been a crime at that time and if they considered it to be a crime now.

The results have been analyzed such that it is possible to demonstrate a number of victimizations having occurred which the first series of official victimization questions did not reveal. Because it is possible that the specific-behavior questions overlapped with other than the intended categories, controlled estimates are also listed. For example, someone who reported having had a window in their car or home broken, may have done so in conjunction with reporting burglary or motor-vehicle theft rather than vandalism. The controlled estimates exclude all “new” crimes revealed which may reasonably have occurred as the result of a victimization reported in another category. Victimizations in which persons reported that the specific-behavior item happened to them but that they do not now consider it to have been a crime were also excluded.

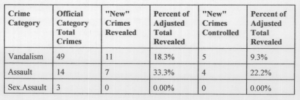

The following table summarizes the effect of adding this second series of behavior-specific questions for victimization: The percent of adjusted total is the percent of victimizations which only the behavior-specific questions revealed, assuming the total number of victimizations includes those “new” crimes. In

other words, the most conservative estimate shows that 9.3% of vandalism behaviors which are considered to be crimes by the respondent were not detected by the official crime category question. 22.2% of such assault behaviors were not detected by official crime category questions. Additionally, two respondents who hadn’t reported being victim of sexual assault, rape, or attempted rape answered ‘yes’ when asked if someone had forced sexual contact with them without their consent (the behavior-specific version). These were not included as newly revealed crimes however because both respondents answered that they did not now consider it to have been a crime.

The behavior-specific series indicates the difficulty in accurately measuring crime victimization. As typically and most easily done, official category victimization questions make unrealistic assumptions about the nature of victims. It would be difficult in any interviewing format to so quickly gain the confidence of victims of personal crimes to be able to assume that a serious evasive response bias does not exist. In addition, official crime category questions assume that the victim can readily classify him/herself as “a victim of __.”

In spite of these measurement difficulties, it is not the researchers’ recommendation that following years’ surveys make whole sale changes in the official category style of victimization questions. It is impossible to measure the real incidence of crime. Any self-report measurement of personal, difficult, or complicated issues are subject to error of human memory, motivation and other factors. The behavior-specific series is useful in indicating the nature of that error. However, in order to usefully compare estimates of crime incidence from year to year, it is important that the measuring instrument remains constant. The researchers recommend improving the victimization battery only in ways that would afford measurements of the change such that year to year comparison will be valid.