John M. Collins and Dr. Macleans A. Geo-JaJa, Educational Leadership and Foundations

The 1980s saw an increase in youth violence, teenage alcohol, and drug abuse. The media is continually bombarding homes with news stories on teenage gang wars, drive by shootings, and school violence. The Department of Justice (DOJ) in its 2001 Report stated that there were 2.5 million students between the ages of twelve and eighteen that were victims of a crime committed on school property in 1999. This same year, the DOJ indicated that of these victims about 186,000 were of serious violent crimes, including rape, sexual assault, robbery, and aggravated assault. In 1999, 2.5 million juveniles were arrested. This accounts for 17% of all arrests made in the United States and 16% of all violent crimes. However, according to the DOJ, juvenile crime has been steadily declining since 1994. Regardless of the decline in trends, recent violent acts on school campuses have become front-page headlines and sound bites on the nightly news. This media attention has changed the public’s perception of youth violence.

My original hypothesis was that students from rural regions, where youth violence has a minimal daily impact on the students’ lives, will reflect the attitudes of the media, and public opinion given to the students by teachers and civic leaders. I believed that students from rural areas will identify with the breakdown of the family, violent media such as video games, the WWF, and students picking on other students as the causes of youth violence. I further believed that the students’ perceptions from rural areas would be different from the perceptions of students from urban areas. I believed that the urban students’ perceptions would be formed from their close proximity to high crime rates, large gang populations, and widespread poverty. The exposure to violence and personal experience were expected to influence the urban students’ perceptions of youth violence. In contrast it was believed that the rural students’ perceptions would be more a reflection of the media than personal experience.

Methodology

The Do the Write Thing Challenge program invites students to submit essays on the causes and solutions of youth violence. The National Campaign to Stop Violence sponsors the program and receives hundreds of essays per city each year. Thirty essays were randomly selected from the essays submitted for the cities of Washington D.C., Houston, Miami, and Chicago for the 2002- 2003 school year. These cities were selected as they were the only cities that had submitted all of the essays to the Washington D.C. office by the day the data was collected. All names of students and schools were removed from the essays as to ensure anonymity before the essays were read.

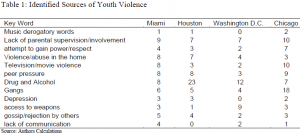

All students were middle school or junior high school students ranging from seventh through ninth grade. Participation in the program was voluntary and was administered by the student’s classroom teachers. A content analysis of the essays was conducted where key words were identified and tracked to evaluate the student’s perceptions to the causes of youth violence. The key words represented trends in the essays that portrayed students’ perceptions of youth violence and were then clustered according to common ideas, beliefs, or stated causes of youth violence. These numbers were then aggregated to indicate city totals for each key word and then used to compare against the totals of the other three cities. As this was an observational study which relied on voluntary response from participants, the essays only reflect the views of a small segment of the youth population and can not be seen as representative of all the youth in the cities or even from the same school. Regardless of the limitations of this approach, the approach does provide insight into the perceptions of those youth that voluntarily participated.

Data analysis

The key words from the essays demonstrated many common themes seen in all four cities. However, the way the essay was framed by the teacher or the local program heavily influenced the students’ responses. It was evident by the titles and themes of many of the students’ essays in Houston that the students were encouraged to write on drug abuse and youth violence. This created a major focus of the writing on the connection between drug and alcohol abuse and youth violence rather than the students’ ideas of the causes of youth violence. Even with the skewed Houston data, overall, family influence, drugs and alcohol abuse, gangs, and peer pressure appear to be the most common causes of youth violence according to the students’ perceptions. The following table includes the main causes of youth violence identified by the students of each city.

Since all four cities can be considered urban, I was unable to compare perceptions between rural and urban youth. However, there was variation in the students’ responses identifying regional differences. Furthermore, how the students identified youth violence was different between the four cities. The students of Washington D.C. and Chicago identified with personal exposure to gangs and drug abuse in their neighborhoods. The students of Houston were mixed between personal experiences and references to media exposure to violence, while the Miami students did not cite as many personal experiences as the students from the other three cities. Although this does not provide scientific evidence to the causes of youth violence, it does provide insight into the problems that students in these cities are facing and ideas of how people can address the issue of youth violence.