David Boren and Professor Paul F. Cook, Teacher Education

Educators are constantly striving to improve and increase student motivation. The less time a teacher spends on motivation and management, the more time can be spent on teaching the subject matter. Behaviorism and constructivism are two theoretical positions on human motivation which can help explain student motivation in the classroom. Greatly simplified, Behaviorism takes the position that people naturally act and will continue to act in a certain way if their actions are followed by an external event that is reinforcing to them. Similarly, a behavior is less likely to occur if it is not reinforced by an external event or is followed by a negative consequence. The focus of motivation is, therefore, on external events. Another important idea in Behaviorism is that once a behavior is learned because of an extrinsic reward, the behavior will continue if there is something in the environment (a natural consequence of the behavior) that is rewarding. This allows the original reinforcement to be faded out. In the school setting, the teacher can evoke desirable behavior through offering students extrinsic rewards; once this is done, the teacher can maintain the desired behavior by presenting interesting lessons without the need of the original incentive. On the other hand, Constructivists believe that students are inherently curious and motivated to learn. Some Constructivist theorists have been very critical of extrinsically rewarding students for something for which they are already intrinsically motivated, claiming that doing so reduces their motivation when the extrinsic reward is removed. The lesson content should be the primary motivation.

During my student teaching experience in Mainland China, I wanted to study whether American student teachers found constructivist or behaviorist methods to be more effective in the Chinese classroom. There were nine teachers, 2 males and 7 females. Before coming to China, each student teacher had two semesters of pre-service teaching experience in an elementary school classroom. The prior two semesters of practical experience were coupled with university methods courses, some of which spent time focusing on theories of classroom management.

In order to analyze and understand their experiences and opinions about constructivist and behaviorist behaviors, a survey was completed by each student teacher at the beginning of their student teaching. I then observed each student teacher, tracking the use of constructivist and behaviorist methods used in their lessons. I categorized specific student-teacher interventions as constructivist or behaviorist, according to important teacher behaviors identified by educational philosophers from both theories. Upon completing their student teaching, the student teachers were asked to complete a post survey. In this survey I asked them to review the first survey that they had completed, indicating any changes of opinion. Upon completing their student teaching, the student teachers were asked to complete a post survey. In this survey, I asked them to review the first survey that they had completed and indicate any changes in opinion. My primary tasks were to evaluate these pre and post surveys to determine the student teachers’ theoretical position, observe the use of their actual methods in the classroom, and finally, assess which method was found to be most effective.

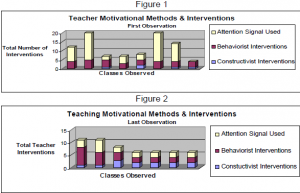

After evaluating the results from the first survey, I concluded that most of the student teachers would primarily use behaviorist motivational methods in their teaching. In completing the observations, I found that for the most part my conclusion was supported by actual teacher behavior in the classroom. Figure 1 shows a comparison of constructivist and behaviorist methods observed in the first observation. It also indicates that those student teachers that used both constructivist and behaviorist methods did not interrupt class as often by using attention signals. Figure 2 shows the same comparison for the final observation. We see in the last observation that constructivist methods increased; those student teachers using an equal balance between each method did not use as many attention signal during the class period.

Another observation was also made. When the student teacher realized that many of the students were off-task, he or she used an attention signal to recapture student attention to get them back on task. Of course, each time a student teacher had to use an attention signal, valuable time was taken from instruction time in the subject matter. Although more instructional time in the subject matter does not necessarily mean that students are engaged in the lesson, they are more engaged when the teacher’s time is spent teaching, rather than disciplining or recapturing student attention. The student teachers that primarily implemented behaviorist methods found that they were using attention signals more frequently than the other student teachers. There was a linear relationship indicating that as the teachers’ constructivist interventions increased in a lesson, their use of attention signals decreased (r= -.90 and r= -.85 for the first and second observations, respectively).

My original question was, is it more effective for teachers to use constructivist or behaviorist methods to increase student motivation with Chinese students? Through this study, I have learned that although students are often intrinsically motivated, such was not the case with every student in every subject. Perhaps a balance between both constructivist and behaviorist methods of student motivation may be the best approach to classroom management and student motivation in China and elsewhere. I am extremely excited as full-time third grade teacher to see effective results stemming from this research project as I attempt to carefully balance both constructivist and behaviorist methods of student motivation in my own classroom.