Scott Jackson and Dr. Joshua Gubler, Department of Political Science

In 2009, the Pew Internet & American Life Project reported that over the preceding twelve months, 67% of Americans “contributed to a charity or non-profit organization other than their place of worship” (Smith et al., 2009). The study also found that 11% of Internet users had gone online to donate money to a nonprofit or charitable organization in the preceding year. In 2002, the Center on Philanthropy at Indiana University reported that the average amount donated by American donor households was $1,872 (Center, 2006). These studies show that modern nonprofits access a large market of potential donors and wealth when they reach out to average U.S. citizens. How nonprofits engage this population and, more particularly, how this population engages with nonprofits, will have significant influence on the incentives nonprofits face and, thereby, how they tie their need for money with their programs serving people.

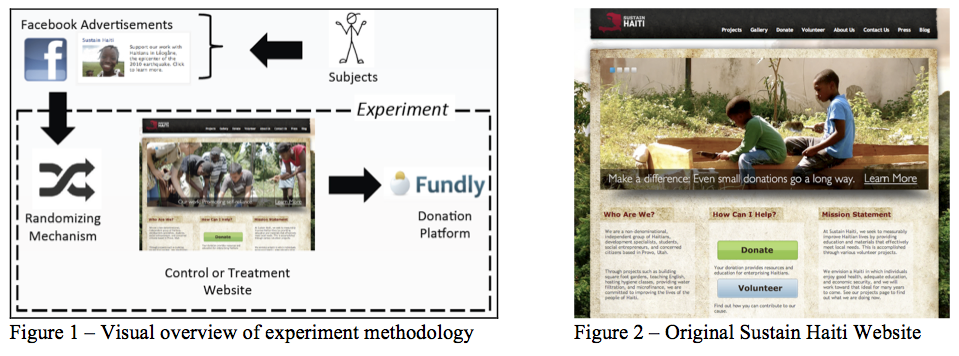

This study investigated three possible means by which Non-Governmental Development Organizations (NGDOs) may entice individuals to give monetary donations other than by proving significant program effectiveness. To determine the influence of 1) development buzzwords, 2) reference to identifiable (as opposed to statistical) victims, and 3) social proof (revealing the support of peers) on an individual’s propensity to donate to a given NGDO, I developed three field experiments. As all three of these persuasive methods are not directly connected to organizational effectiveness, the results of these experiments revealed the degree to which money and mission are divorced (or aligned) in the everyday fundraising efforts of NGDOs. To increase the realistic feel of this experiment, I used an actual NGDO, Sustain Haiti, in these experiments.

This thesis began as a simple class project. However, as it grew and matured into a BYU Honors Thesis, it became something much more than that. Its focus shifted and where once it had concerned itself only with the relationship between buzzwords and donation rates, it soon became an investigation into new methods of experimentation—something with much wider implications. While the primary purpose of this thesis in my mind had, for a long time, been the first of these two focuses, the end result has been to give few if any answers about donation rates, but many new lessons about both what does and does not work in experiment methodology.

For the first of several pilot tests, Rachel Fisher—another student in my PL SC 359R class— and I designed a simple Qualtrics survey to distribute to friends and student organizations at BYU. The survey randomly presented one of two brief descriptions of Sustain Haiti to each subject then allowed them to donate by clicking on a PayPal “Donate” button. However, after a lengthened trial period with almost no response from contacted subjects, we determined this was a less than optimal testing platform.

This proved a useful pivot point for me as I began to redesign the experiment. To overcome the discouraging dearth of donations, I shifted the target audience from a predominantly college- aged population to a more representative population through creating a Facebook Advertising campaign. I also lessened the “cost” of participating in this pilot by testing only whether subjects became interested in learning more about Sustain Haiti. Lastly, I expanded my possible statistical controls by collecting more background information about each subject. Finally, I included a link to Sustain Haiti’s webpage and tracked whether subjects followed the link. This phase, however, also ended in few responses. After seven months of operation, it had recruited only 28 subjects and only seven subjects had responded to my survey’s questions.

While this phase taught me a great deal about the potential of Facebook advertisements as a subject recruitment tool in experiments, it revealed little to nothing about donation behavior. Perplexed but undaunted, I worked with my Adviser and with Rachel Fisher, who was still assisting in the research for Study 1, to develop possible alternate strategies. It was amid these deliberations that an “ORCA Grant Miracle” happened. My Honors Thesis Advisor, Dr. Daniel Nielson recruited a professional website analyst to provide pro bono technical support for our research. With this connection, I set to work designing a website to mock Sustain Haiti’s actual website with the hope that this would attract more responders and enable more advanced data collection. However, we faced disappointment again as we began to realize that the server access and web language skills actually required were far beyond both my and the professional’s abilities.

Thus, I reached a detour. Facing all these challenges, I have chosen to end the research at this stage. Although disappointed that this thesis did not bear the scientific results I had hoped, I feel that it does lend valuable insight into innovative experimental methods, particularly regarding the use of social media and the Internet to administer powerful randomized control trials.

More than anything, this thesis stands as an insight into the scientific process. No discovery is easily earned and the pathway to discovery is anything but direct. Rather, discovery follows a winding trail of trial and error, with each step yielding priceless lessons even if not answering the original question.

References

- The Center on Philanthropy at Indiana University. 2006. Average and median amounts of household giving & volunteering in 2002 from the Center on Philanthropy Panel Study (COPPS) 2003 Wave. Indiana: The Center on Philanthropy at Indiana University. http://www.philanthropy.iupui.edu/ (accessed 18 Nov. 2011).

- Smith, A., K. Schlozman, S. Verba, & H. Brady. 2009. The internet and civic engagement. Pew Internet & American Life Project. Washington, D.C.: Pew Research Center. http://www.pewinternet.org/ (accessed 18 Nov. 2011).