Peter Sturgeon and Dr. Daniel Nielson, Political Science

This project examines the relationship between increases in human capabilities and growth in GDP per capita. To do so, I utilize two-stage least squares regression analysis of cross-sectional data from over 140 countries. The results show that income and human capabilities have independent effects—with the effects of increases in human capabilities being greater. The role of human capabilities in increasing income is primarily realized through marginal increases in labor productivity. The findings suggest that development efforts focusing directly on education will be the most effective at alleviating poverty and empowering individuals.

Although not mutually exclusive approaches, the division between income and capabilities remains a salient issue in development studies. The income approach emphasizes the importance of economic liberalization, foreign direct investment, national savings rates, and other macroeconomic indicators of stability. Scholars favoring the capability approach, led by Amartya Sen, argue that investment in human capital is a goal in itself because capabilities directly improve quality of life. Sen contends that a country can dramatically improve quality of life “without having to wait for ‘getting rich’ first”. The capabilities approach focuses on individual’s access to health care, education, credit, and political and economic opportunity.

Increased capabilities, especially education, increase a country’s supply of human capital—which increases production efficiency. This is the key causal mechanism in the relationship between education and per capita income. Increasingly skilled labor also allows firms to introduce more advanced technological production methods. In 1956, Robert Solow argued that improvements in technology are the primary cause of long term economic growth. The Solow model uses increases in the marginal product of labor to explain growth in income . Programs that increase human capabilities increase the marginal product of labor and thereby contribute to growth in per capita income.

As a quantitative study, I focused primarily on econometric analysis to determine the relationship between income and capabilities. Because income and capabilities are clearly related, a simultaneous equation model is used to account for this endogeneity problem among the dependent and independent variables. Social loans from international development banks are the key instrumental variable in this simultaneous equation model. Loans work as an instrumental variable because they affect educational outcomes but not income per capita.

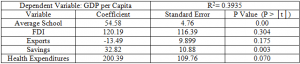

The key independent variable in this study was the average schooling completed—a measure of the percentage of students of a particular age completing a secondary education. I also included several control variables to capture the effects of the key mechanisms employed in the income centered approach to development. These include net inflow of foreign direct investment as a percent of GDP, each country’s exports as a percentage of GNP to indicate a country’s openness to trade, and each country’s savings rate as a percentage of GDP. The results from the main two-stage least squares regression using average school as the key independent variable are summarized in the table below. Because of the endogeneity between income per capita and education levels, the analysis was also performed with the percentage of students completing a secondary education as the dependent variable. The results of this regression are not reproduced here due to formatting restraints.

Schooling clearly has a significantly positive effect upon GDP per capita. An average increase of one percentage of students completing a secondary education increases GDP per capita by $54.58 ceterus peribus. While this result is statistically significant, the practical significance of this relationship will vary across countries. For instance, in India GDP per capita was $470 in 2002 . Educating one percent more the population would increase per capita income by approximately 12 %. Meanwhile, increasing the number of students completing a secondary education in Brazil, a more wealthy country, would only increase per capita income by approximately 2%. Interestingly, while the regression results indicated that increases in per capita GDP also have a statistically significant positive effect on the percentage of students completing a secondary education, GDP per capita would have to increase by approximately $178 for the percentage of students completing a secondary education to increase by one percent.

The research presented in this paper provides support for the human capabilities approach for development—mainly that education has a larger impact than does increasing GDP per capita. Investment in education does significantly increase average incomes while expanding the quality and quantity of choices available to individuals in developing countries. Increases in labor productivity are a convincing causal mechanism in the relationship between capabilities and income. Thus, even without considering the individual benefits of empowerment, this study supports Sen’s claim that “the more inclusive reach of basic education and health care, the more likely it is that even the potentially poor would have a better chance of overcoming penury”.

References

- Sen, Amartya. 1999. Development as freedom. New York: Random House.

- Solow, Robert. 1956. A contribution to the theory of economic growth. Quarterly Journal of Economics 70 (January): 65-94.

- Mankiw, N. Gregory, David Romer, and David N. Weil. 1992. A contribution to the empirics of economic growth. Quarterly Journal of Economics 107 (May): 407-37.

- World Bank. 2003. Country Groups. At <http://www.worldbank.org/data/countryclass/ classgroups.htm>. 3 December 2003.