John Harris and Dr. Wade Jacoby, Department of Political Science

The magnitude of Chinese outward foreign direct investment (FDI) flows has skyrocketed in the past decade. In the wake of the Chinese “Going Out” policy, many high profile Chinese firms are buying up companies in all regions of the world. It is curious that Chinese firms are poised to allocate large amounts of capital abroad so early on in their development. But what is more puzzling is the destination of outward FDI from China. Typically, a country’s FDI is determined by economic, cost-cutting motives. Chinese firms, however, tend to focus on areas that do not maximize their economic returns. This is especially the case in the European auto industry. To explain this business behavior, this paper looks at the interaction between high profile auto firms and the Chinese government and how that relationship determines FDI decisions in Europe. Through some aggregate data but then, more importantly, a qualitative look at the Chinese presence in the European auto industry, I conclude that Chinese FDI is less a traditional economic strategy than it is a geopolitical advance to regions that possess valuable long-term assets, including natural resources, key technologies, brands/prestige, and advanced management structures.

Introduction and Background

Giorgetto Giugiaro, an Italian car designer, said, “It took Japan 40 years to become a great automotive nation. It took South Korea 20 years. I think it will take China as little as 10 to 15 years” (Shaker 2010, 1). In the 1970s China underwent a set of economic reforms that completely restructured the country’s way of doing business. China began to allow entrepreneurs the opportunity to start their own enterprises. Additionally, many international barriers came down, allowing multi-national corporations (MNCs) to set up operations within China. Not only did China offer a massive workforce for low-skilled jobs, the country’s lax legal environment facilitated foreign investment (Fung 2002, 14). China took off, growing at an average of 9.8% per year since 1978 (Kuijs 2005, 2).

Two decades later, China would implement another round of development reforms. In 1999, the People’s Republic of China (PRC) initiated the “Going Out Policy” aimed at turning Chinese development efforts towards the global economic arena. The Going Out Policy was enacted with the purpose of finding a place for the massive amount of foreign reserves the Chinese government had accumulated. The government bolstered state-run councils for foreign investment and allowed state-owned enterprises (SOEs) access to favorable financial conditions for foreign investments. The China that was once only a prime location for FDI began moving into all parts of the globe, investing in a diverse array of sectors and regions (UN 2004).

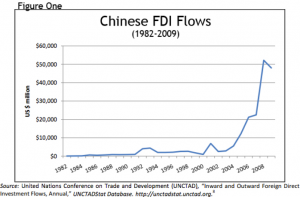

Suddenly, a nation with a per capita GDP of under $9,000 was investing large amounts of capital overseas. In 1980, Chinese outward FDI flows reached a mere $100 million. By 2009 flows were up to $57 billion. Most of this growth occurred after the implementation of the Going Out Policy in 2000. Flows jumped from $26 billion in 2007 to $56 billion in 2008—a 110% increase (Salidjanova 2011). This type of growth in foreign investment is rare among countries and completely unheard of among developing countries like China [See figure one].

Why does a country like China—relatively poor and underdeveloped—find it in its interest to invest in developed regions like Europe? This is puzzling on several levels. In fact, the scale of the influx of high-profile firms into Europe in the past decade has been an unprecedented anomaly because of the location decisions and unorthodox behavior of Chinese firms in Europe. To explain why this happened, my paper draws data from a wide range of different sources. Because Chinese FDI in developed countries is a fairly new trend, there is a shortage of comprehensive data. The data presented here are pulled together from disparate sources, such as the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) investment records, publicly available balance sheet information from an array of MNCs, and the Ministry of Commerce for the PRC, among others. No single source provides comprehensive data, but when viewed as a whole, the data provide a useful mosaic that indicates certain trends.

Chinese outward FDI in developing regions such as Africa has received much more attention than has Chinese activity in developed regions like Europe. Through an extensive effort to locate and aggregate such information, my paper provides a reasonable basis for understanding the geopolitical motives of Chinese business activity. I am confident this paper represents a reliable, if still preliminary step towards revealing China’s strategy in Europe, and more broadly, the entire global economy.

FDI Motives

The Auto Sector and Traditional FDI

This study uses the European auto sector as a case study because this particular sector is a prominent part of the European economy. The many aspects of research and development (R&D), production, and sales make the auto industry observable from many different angles, including green field investment, mergers and acquisitions (M&A), component manufacturing, distribution, administration and assembly. For this reason, Chinese firms have found ample opportunity to become integrated into one of Europe’s key industries. China’s move into Europe’s auto sector demonstrates anomalous behavior by transnational investors because Chinese investment does not always go to places where China has a comparative advantage. Instead investment trends display unconventional motives—based more on the acquisition of reputation-building assets instead of profits.

This section will explore the previously explored theories of FDI motivation, focusing on European FDI trends in the auto sector. With the advent of advanced transportation and communication technologies, global business strategy has become increasingly lucrative, often overshadowing domestic endeavors. But every willing investor must make the decision about where they will invest. After the fall of the Soviet Empire, Central and Eastern Europe (CEE) became a real life laboratory for measuring FDI motivations. The flood of western investors into the newly capitalist East displays a very concentrated sample of FDI operations and allows for a somewhat controlled analysis of FDI motives. After 1990, traditional FDI motivations in CEE initially were seen as a typical ‘profit-maximizing’ endeavor, no different than other fundamental economic motivations that are based on profit-seeking assumptions. For example, one theory suggests post-1990 investments in CEE went to regions where infrastructure was developed, legal environments were lax, and new markets were available (Kalotay 2000). This perspective was later challenged, and a second major theory became popular. Nina Bandlj argued that FDI in CEE was influenced more by relational and ethnic ties to host countries than purely profit maximizing incentives (2008). Using in-depth case studies, as well as aggregate data, Bandelj concluded that MNCs were not just profit maximizing machines looking for the most lucrative investment opportunity. Instead, she found that firms are fueled by a combination of economic and relational motives such as common cultural and ethnic values. Thus, according to Banelj, FDI decisions have a much richer set of motivational nuances at play than just profit maximization.

Chinese FDI’s Place in the Theories: An Alternative Perspective

How do China’s FDI patterns fit these two widely accepted theories? As we will see in the next section, Chinese FDI trends do not easily fit either. Instead, I will suggest Chinese firms—often backed by state-run financial entities—go abroad with motives that are not immediately apparent but are designed to strengthen national economic interests (rather than firms’ profits alone). Chinese investment behavior in the European auto sector exemplifies a number of important trends. First, Chinese firms are looking for technology. Through M&As, Chinese auto firms are investing not only in Europe’s large market, but also in technology licenses and production practices not readily available in China’s domestic auto sector. Second, China is looking to boost their reputation through the acquisition of reputable brands. This search for prestige is a clear example of geopolitical investment and unconventional FDI motives because it motivates firms to invest in economically unpromising corporations and locations with the main return being renowned brands and an increase in reputation. And finally, China is looking to invest in areas where firms can integrate with the quality control/management capabilities of western producers. China is not known for making quality autos; Europe is. As a result, China’s move into the European auto industry has much to do with the desire to improve their reputation for quality. A Rhodium Group study on Chinese OFDI to Europe states “the acquisition of rich world brand or a technological edge is the key element for breaking away from a fiercely competitive pack back home”(Hanneman 2012). These three main motives (technology, brands, and quality), represent a theory of FDI motivation not previously an important part of the debate in Europe. The next section will look at each motivation in depth through aggregate data as well as case study evidence.

Data, Tests, and Analysis

Revealed Comparative Advantage

Before looking at specific motives of Chinese outbound FDI, it is important to demonstrate that China is indeed investing in regions and sectors where it has no obvious comparative advantage. To test whether or not China invests in profitable areas, I used the Revealed Comparative Advantage (RCA) approach originally developed by Hungarian economist Béla Balassa (1965). Bijun and Yiping’s 2011 study on Chinese RCA uses export data from different countries in a specific year and industry. If the model produces a value greater than one, the country is said to have a comparative advantage in that specific industry. The study runs data through an RCA model and shows that China has a strong comparative advantage in the goods industries relative to most other countries. This is no surprise. The surprise is which sectors Chinese FDI flows are going to. Sectors where China has the strongest comparative advantage (construction, goods, and computer and information) only account for 8% of outbound FDI flow (2009). On the other hand, FDI sectors where China has the weakest RCA (services) account for 71% of flows. These trends show something different from traditional investment patterns where firms invest in regions where their country has a relative advantage and hence a higher chance for profits. This paper does not explore extensively the quantitative data pertaining to FDI flows. Instead, I will use the Balassa model evidence as a foundation to explain a more specific case, namely, Chinese business activity in the European auto industry and the motives behind it.

Chinese Auto Firms in Europe

The Chinese auto sector is an example where China has no comparative advantage. Moreover, China is known throughout the world as a producer of low quality cars that do not comply with international safety and emissions standards. Domestic demand for cars within China is enough to sustain a massive market for many Chinese auto firms. By contrast, Europe is a world leader in auto production. Unlike China, Europe is known for producing high quality cars. Yet China has shown a strong interest in European auto companies, even when those companies face higher costs and a more stringent legal environment.

China’s largest international auto firm is Chery Automobile Co. LTD. For over a decade, Chery has been expanding its production operations in Italy. Not surprisingly, Chery is a state owned enterprise (SOE) that is known for its aggressive business growth strategy. While every other Chery location is in a developing country (i.e. Venezuela and Myanmar), Chery continues its large-scale production in Europe, teaming up with western-style carmakers like Israel Corp and DR Motor (Motoren 2011) to increase sales in Europe. Chery bought out a Fiat production plant in Termini Sicily last year, further integrating the company into the European market. Chery’s decision to set up large-scale undertakings in Europe contradicts the company’s broader specialization in producing cheap, low-quality autos for developing countries that do not require strict safety standards. Instead, Chery seems to be searching for something more than just immediate profits. As the largest Chinese auto firm, Chery is seeking better management resources that a much more auto-experienced region like Europe can offer. Chery General Manager Lu Jianhui stated last year that Chery would be focusing in on developing countries in Asia and South America, but that the company was looking to expand its production in Europe as well. This expansion is odd because Chery specializes in cheap autos, selling to primarily developing nations. Through joint ventures with western firms, Chery is learning the ways of European car production. This process is emblematic of many Chinese firms in Europe seeking better management capabilities to send home to domestic operations.

Another reason many analysts say China’s move into the European auto market is puzzling is because the European auto industry is a saturated market in decline for several years (ST Motoring 2012). An important trend that provides insight into China’s unique FDI motives has to do with the types of auto firms Chinese investors buy. For example, Youngman—a Chinese auto assembly firm—was interested in buying GM-owned Saab in early 2011. GM refused, not wanting to give up technology licenses to Youngman.

Yet, even when Saab filed for bankruptcy, the Chinese firm was still intent on purchasing it even in spite of Saab’s financially weak state. In January 2012, Youngman teamed up with an unidentified Chinese state-owned bank to wage another bid, this time offering over 1 billion Euros to acquire the Saab (Ramsey 2012). GM continues to resist the deal. Independent automotive analyst Zhong Shi has noted, “it’s rare for a state-owned bank to directly purchase shares in a foreign car maker” (De Feyter 2011). Youngman is after reputable brands like Saab, apparently regardless of the poor financial state of the company. This is because, up until lately, China has had no prominent brand in the western auto industry. With the potentially imminent takeover of Saab by Youngman, China would inevitably become a more noticeable actor in the global auto sector.

In 2010, the high-profile Chinese firm Geely Automobile Holdings Ltd bought Volvo. That year, Volvo sales were down 11% from the year before and 27% from its peak (Welch 2010). Again, buying European firms in decline is a trend with Chinese auto firms. Even so, Geely paid $1.8 billion for the brand. A Geely spokesperson suggested, “The leaps and bounds made in manufacturing mean that China’s car makers are rapidly closing the gap with Europe’s establishment. We will be aiming to widen our range just as quickly as possible, probably at least a new model range every year for the next four to five years.” It is clear that in spite of Volvo’s decline, Geely is ambitions about turning the company around in order to ‘close the gap’ between European and Chinese autos. Geely is not deeply integrated with the PRC and thus not as subject to government influence as some other auto firms; however, the firm is still subject to state approval and influence (Welch 2010). According to analysts, “…while it might be considered surprising that Chinese firms are so determined to get into Europe, a saturated market where car sales are declining, there are benefits for them, especially in terms of branding and prestige (ST Motoring 2012).” Thus, Chinese firms do seem to be searching for high profile brands in Europe, an asset that will give China a more prestigious standing in the world economy. This is another component of Chinese geopolitical investment, using brands and prestige to empower the state.

In February 2012, Chinese firm Great Wall Motor Co erected a greenfield production plant in Bavhovista, Bulgaria—joining forces with the local Litex Motors. The production plant represents a big step for the Chinese auto sector as the Great Wall plant is the first Chinese-built auto facility in Europe. Why is China interested in setting up a plant in Eastern Europe? With the Chinese auto market strong at home, a move so far to the west seems impractical. Like the other stories of auto firms in Europe, Great Wall wants something more than profits. While Great Wall Motors is said to be a privately owned company, most experts agree the firm has ties—whether direct or indirect—to the Chinese government (Dog & Lemon 2011). Great Wall is the second largest exporter in of autos in China. As the firm grows while also complying with the government’s conditions, investing in a place like Eastern Europe seems like a wise strategic move. Hermes analyst Yann Lacroix says, “It is a way for them to make progress in quality levels (AFP 2012)” referring to the advent of low quality Chinese producers in Europe. Great Wall sees this greenfield endeavor as a way to raise the bar for their autos. It can be safely assumed that the Chinese government sees an investment like this as an important step towards integration into the quality auto standard of western producers.

SOEs

Behind each of these stories is a firm connected to the Chinese government. The PRC has connections to most, if not all, prominent business endeavors abroad (Salidjanova 2011). China’s business behavior is puzzling until the role of the state is considered. Considering the nature of state intervention, it is not hard to understand why Chinese firms do not behave like typical capitalistic MNCs. State interests have a large effect on transnational business conduct.

SOEs are a central to this paper since 70% of Chinese outbound FDI flows are from SOEs. Data on SOEs is hard to come by, however, it is undisputed that the Chinese government has a substantial role in the priorities of business activities domestically and international (Economist 2011). State owned banks offer capital loans with lower rates and looser stipulations to SOEs. This advantage fuels the growth of many Chinese SOEs and more recently has been the cause for an explosion of state-backed operations abroad. Additionally, the Chinese government offers generous subsidies to sectors dominated by SOEs, thus facilitating their expansion. Boards and councils are in place to organize this state intervention. One such entity is the Chinese Investment Corporation (CIC), a staterun council that decides where to allocate China’s massive foreign reserves. Because of these state run entities, Chinese FDI is bound to be influenced by the state’s interests. As we’ve seen, this is the case with capital flows to the European auto industry.

Conclusion and Further Questions

While China’s growth path has long been associated with the reception of FDI in manufacturing sectors, recent trends in outbound FDI have substantially complicated the overall picture. China has become a major actor in the outbound FDI arena. It is certain that China’s strategy for outward FDI is does not easily fit into the previously explored theories about FDI motivation. However, a survey of investment trends suggests China is adopting a geopolitically-savvy agenda, using state-owned and state-influenced enterprises to captures assets in all part of the world.

The case of the European auto industry is provides some insight about China’s strategy. Big firms have shown a keen interest in acquiring prestigious auto companies, even when those companies are in decline or bankrupt. Further, Chinese firms have shown that they sometimes value reputation and prestige over profit maximizing alone. In other cases, Chinese firms appear to be searching to revamp their quality control— something the renowned European auto sector offers. Through transnational operations, Chinese auto firms have raised their standards for auto production. This is one of the key motivating factors for China’s presence in Europe. Finally, Chinese firms are after technology that is not readily available in domestic industries or in developing countries. China sees the acquisition of technology licenses as a long-term benefit to economic goals (Huang 2011). It is for this reason that Chinese auto firms have continually pushed to merge with European producers that hold superior technology capacities.

The motives discussed here can be summarized in few words: China wants to bolster its reputation in the world and is influencing transnational business operations to do so. These trends are not always obvious on the surface, however, understanding this new style of FDI becomes important as the Chinese economy grows and the European economy suffers. Geopolitical FDI from China should thus be a relevant topic when discussing the future of Europe. If the trends continue, will China use economic influence to gain more political leverage in the European Union? The idea seems far off at this point, but it is hard to ignore the growing influence that China is gathering in Europe.

References

- AFP. (2012, February 20). Chinese auto firms buy into European markets. Taipei Times.

- Bandelj, N. (2007). From communists to foreign capitalists: The social foundations of foreign direct investment in postsocialist Europe. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Chang, V. (2009). Facilitation of Chinese outbound investments to European countries. Business Management Trai, (32).

- Chery auto and Magna developing cars for Europe . (2011, September 25). Morton

- Chinese automakers buy into European car firms . (2012, February 20). ST Motoring.

- De Feyter, T. (2011, December 6). Saab talking to a Chinese bank, not bank of China . Car News China.

- Fung, K.C., Iizaka, H., Tong, S. (2002). Foreign direct investment in China: policy, trend and impact. China’s Economy in the 21st Century, 2-34.

- Great wall motor. (2011). The Dog & Lemon Guide.

- Hanemann, Thilo, and Daniel Rosen. 2012. China Invests in Europe: Patters, Impacts and Policy Implications. Rhodium Group (June): 20-25

- Kalota, K., & Hunya, G. (2000). Privatization and FDI in Central and Eastern Europe. Transnational Corporations, 9(1), 39-66.

- Kuijs, Louis, Wang Tao. (2005). China’s pattern of growth: moving to sustainability and reducing inequality. World Bank Policy Research Working Paper, 3767, 1-13.

- Kornecki, L. (2008). Foreign direct investment and macroeconomic changes in CEE integrating into the global market. Investment Management and Financial Innovations, 5(4), 124-132.

- Ramsey, J. (2012, January 19). China’s Youngman to wage new bid for Saab. Autoblog.

- Salidjanova, N. (2011). Going out: An overview of China’s outward foreign direct investment. U.S.-China Economic & Security Review Commission, 1-38.

- Shaker, N. (2010). Internationalization strategies of the Chinese automotive industry: Challenges and a plan for going global. Master’s thesis in International Business.

- The long arm of the state. (2011, June 23). The Economist.

- UN Report. (2004). UN report: China becoming major investor abroad. Beijing Times.

- Welch, D. (2010, March 29). Geely buys Volvo. Believe it or not, it could work. Bloomberg Business News.