Brandon Dean and Dr. Macleans Geo-Jaja, Educational Leadership and Foundations

Public health educational campaigns are an important part of the health care systems of the world. From public service announcements pleading with us to not “Drink & Drive,” to large outdoor billboards advertising the “Fight the Bite” campaign against West Nile Virus, public health education plays a key role in the health and well being of our own and many other societies.

In the tropical country of Brazil, a country with a landmass nearly equal to that of the United States, and with a population of slightly more than 184 million, there are many public health concerns that need to be addressed. One of the chief concerns revolves around a tiny mosquito, Aedes aegypti, the Egyptian mosquito that carries and spreads a debilitating disease known as dengue fever throughout the Brazilian population with alarming success.

The Problem

Known as “break bone fever” here in the U.S., dengue fever, a pervasive viral disease, annually afflicts 50-100 million people each year, killing slightly more than 5% of its victims. The virus causes severe fever, head and body aches (myalgias) and hemorrhaging . A vector disease, it is directly carried and spread via bites by the Aedes aegypti mosquito, which unlike other mosquitoes primarily feeds during daytime hours. There is no effective medicine available to treat the illness. A preventable vaccine against dengue does not exist. The best preventive tools remain public awareness and education.

Dengue was first reported in the Asian and African continents during the 18th century. Following another century of a relatively isolated existence, dengue fever began to spread, particularly aided by increased global travel in the post WW II era. The disease burden soon was prevalent throughout the American continents. Among the countries hardest hit was the nation of Brazil; where ideal climate conditions, a struggling health care infrastructure, population size and demographic location have combined to form a dynamic opportunity for the spread of dengue.

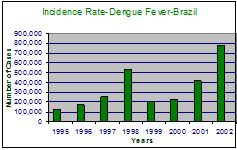

While dengue epidemics in Brazil have historically varied in strength and concentration, recent epidemics, particularly in the past 10 years have been particularly strong and destructive. In 1998, the number of dengue cases spiked at 535,388, a 110% increase over the previous year. With a continually growing urban population and a stressed health care system, there was significant alarm concerning dengue fever. In response, the government started an externally driven public health campaign aimed at chemically destroying the breeding process of the tiny mosquito. The monetary costs of this program were extremely high, over 448 million US dollars. Unfortunately the program was largely ineffective. After some initial success in 1999, the incidence rate continued to climb the following years; reaching 413,067 cases in 2001 and soaring to 780,644 in 2002, a 45% increase over 1998. The government’s efforts and programs were ineffective and misdirected.

Better Solutions?

The ineffective anti-dengue program consisted of a chemical treatment applied to the sinks and drains in millions of Brazilian homes. While some resources were directed to public education regarding dengue, the efforts were too little, too late; the incidence rate of dengue has continued to climb. The solution to the dengue problem lies not in misdirected operational strategies, but in health education and community participation.

Worldwide health organizations such as the CDC and PAHO have for several years continually stressed the need for “community based health education and participation.” What about the Brazilian voice concerning dengue fever? What are the peoples’ concerns? Are the current anti-dengue programs making them safer? What, if any feedback do they have to share? This research project was designed to provide answers to those questions from a very small sample of the Brazilian population.

Designing my research and methodology around participatory-based guidelines, I prepared a simple interview and survey to conduct with the population in the city of Rio de Janeiro Brazil. With its climate, topography and dense urban population, Rio de Janeiro continually struggles in its fight against dengue fever. At several locations throughout the city, I randomly selected and conducted interviews with 20 individuals. The two-part interview consisted of a simple questionnaire designed to encourage discussion and feedback responses. Each individual’s responses and feedback were recorded and analyzed.

Results

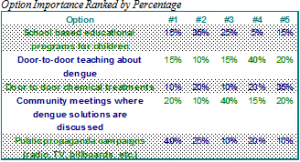

Part A: Individuals where asked the following question: Which of the following 5 options do you consider the most important in the fight against dengue (rank each one according to importance).

Conclusion

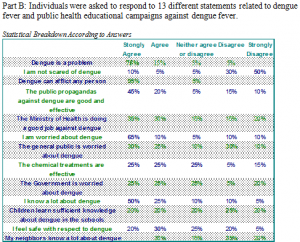

Dengue is a problem for the Brazilian nation; the results of this study echoed that sentiment: 75% of the people interviewed strongly agreed that dengue is a problem, another 65% replied that they are worried about the disease. While the effects of dengue are easily quantifiable, the direction and effectiveness of governmental responses to the threat are less clear and more debatable. The results show that there is no clear consensus that the government is or is not meeting their needs: Some individuals felt the public health campaigns were effective, others did not.

The discrepancy is primarily due to the unequal distribution of health care resources throughout Rio de Janeiro. Individuals who felt “safe” against dengue generally lived in more affluent communities; communities, where according to some, schools receive federal funding to perform plays aimed at teaching the children about dengue prevention. Individuals from less affluent communities noted that such programs did not occur in the schools of their children. Some individuals noted that they had received in home teaching concerning dengue, others had not seen a dengue official in their neighborhood in years.

For Brazil to have any real hope of controlling dengue fever, improved health care delivery systems, rooted in community based participation and free from inequalities must be not only be designed, but effectively implemented in all communities, regardless of geographic location or socio-economic status.