Cynthia Lee Killian Young and Dr. Marti L. Allen, Department of Anthropology

The adventure of planning and creating a museum exhibition began September 2003. While other museums may take a year or more to install a series of exhibits, we at the Museum of Peoples and Cultures (MPC) were able to create a professional exhibition in eight months. My whole project centers on a collection of Virgin or Western Anasazi artifacts that Mr. Lanny Talbot retrieved from his lands. The Talbot collection is one of the largest collections of Western Anasazi pottery allegedly found from one site.

Unfortunately, this precious collection will not always remain in the hands of the MPC. The collection will be returned to its owner. Thus, my goal in this project was to preserve as much information about every artifact, research the lifeways of the Virgin Anasazi, and share that information. Even though the collection will disappear from the public, its beauty and secrets will be preserved for future research.

In my first semester of research (Fall 2003), I studied a number of bowls that are painted on the interior and corrugated or rippled on the exterior. Corrugated wares are the most common pots that were used for cooking and storage (see figure 1). Pots with painted designs are rarer and were used for serving, decoration, and ceremony. The rarest types of pots are those that combine the common corrugations with painted patterns.

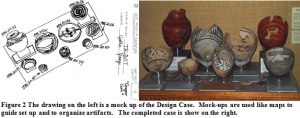

After I completed my paper on painted and corrugated wares, I decided to shift my focus to another topic in January 2004. Anasazi painted designs are generally black geometrical shapes painted on a white, gray, or red background. By observing the design layout on painted ceramics, my mentor, Dr. Marti L. Allen, noticed that the shapes left in the empty white space—also known as reserve or negative—were just as intentional as the painted black designs. My research shows the different techniques craftswomen used to capture reserve shapes and explores possible motives such as ideological expression (e.g. releasing spirits, seeing the unseen, communicating abstract concepts, etc.) or representation of nature. While engaged in this last paper, I worked many hours to design an exhibition that would communicate these complex ideas. Each display case was meticulously designed or “mocked up” (see figure 2, below). Museum learning is heavily based on visual aesthetics, so I made sure that each piece would be aesthetically inviting so that every visitor could appreciate the beauty and significance of these artifacts.

Anther large task in making an exhibition is to write labels. At first it may seem simple, but a label must be more than just a tag telling the viewer what an object is. I compiled some labels that just contain the essentials such as origin, date, and style. I also wrote text labels. A good text label is one that translates very technical, academic terms into something that most people can understand and appreciate. All together, labels guide the visitor through the lifeways of an ancient people.

We also labored to design rock art paintings and interactive stations. Then, on the week before the grand opening of the exhibition, my colleges and I worked late into the night to install all the artifacts and interactives. On the opening day, we held a street fair in conjunction with Utah’s Prehistory Week, which brought about 200 attendants to the MPC. The exhibition will be on display for the benefit of BYU and the public until April 2007. In addition to having the exhibition open to the public, we have had speakers share their findings on the significance of the Talbot collection, and we have had open houses were people could come ask researchers questions about these artifacts. The Museum is also expecting to publish a catalog of the Talbot collection that I helped to write.