David N. Hanton and Dr. Ray T. Matheny, Anthropology

In the 1880’s the Texas cattle barons brought thousands of sheep and cattle to Utah to exploit its grasslands.1 Some of them made their way to Montezuma’s Canyon. The purpose of my research in Montezuma’s Canyon was to determine if there is a correlation between the commencement of farming and herding and the acceleration of erosion in the past 120 years.

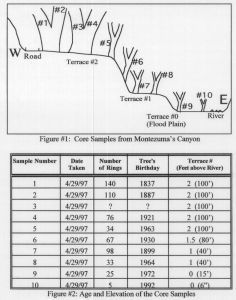

A study by Womack reported that the introduction of large numbers of livestock can start the process of canyon cutting in which a river erodes through a floodplain leaving terraces.2 Cottonwood trees, which always begin their growth cycle on the current floodplain, can be used to date the terraces.3 Any given terrace is at least as old as the oldest cottonwood growing on it. It is possible to determine the age of a tree by driving a hollow coring tool into the tree, extracting a cylinder of wood, and counting the growth rings. By taking extensive tree samples at various elevations in the canyon, I created a contour map containing the age of each terrace.4

The results of my study show that there has been substantial erosion since the arrival of the cattle barons in 1880. Since then, the river has cut canyons of various depths through the floodplains on which the cattle first grazed: 30 feet deep near the mouth of the canyon, 50 feet deep 10 miles further into the canyon, and 100 feet deep 20 miles into the canyon. From these statistics, I estimate that the canyon cutting has taken place at an average rate of 4 inches per year (30ft./117 yrs.) near the mouth of the canyon and 1 foot per year (100ft./117yrs.) 20 miles into the canyon. This high rate of erosion is caused in part by the clearing of land which was documented by comparisons of aerial photographs from the early 1960’s and recent photographs. The effects of erosion caused by land clearing are obvious farther downstream, where, in a slow-moving meander, massive amounts of eroded soil are accumulating. The 1960’s aerial photos show that there was a deep gorge in this section of the canyon before the land upriver was cleared. Recent photos show that accumulated sediment has filled in the gorge and widened the floodplain.

The stone and log buildings of the Anasazi suggest that southeast Utah once grew trees and was not always a desert. Dr. Ray T. Matheny explains this apparent enigma by proposing that the overutilization of resources caused desertification and the collapse of the Anasazi culture. This should be a powerful warning to those who live among the empty granaries of the Anasazi. A comparison of erosion rates during the Anasazi period, the non-occupation period, and the Anglo-period could be instrumental in proving his theory. Unfortunately, most of the trees sampled were not old enough to provide data on the pre-1880 enviromnent. I probably could have shown that four of the trees sampled were from the 1700’s had I been able to use a longer coring tool. More extensive research should be done on this exciting cultural comparison between the Anasazi Indians and the Angloherders and their impact on the environment.

References

- Peterson, Charles S. “Grazing in Utah: A Historical Perspective.” Utah Historical Quarterly 57.4 (Fall 1989): 300-19 94

- Womack, W. R. “Terraces of Douglas Creek, Northwestem Colorado: An Example of Episodic Erosion.” Geology. 5.2 (February 1977): 72-76

- Everitt, Benjamin L. “The Cutting of Bull Creek Arroyo” Utah Geology. 6.1 (Spring 1979):39-44

- Everitt, Ben L. Use of the Cottonwood in an Investigation of the Recent History of a Flood Plain. American Journal of Science. June 1968: 417-439