Daniel M. Cloward and Professor George R. Ryskamp, Family History

I chose to study the conflict between the Catholic Church and the new Spanish government during its reign of 1868 to 1875. In 1870, the government passed a controversial civil marriage bill, requiring each couple who wished to marry, to marry first by the State’s authority and then if they so wished to marry by the Church.1 If they did not follow this law, their marriage would not be legal and hence all offspring would be illegitimate.2 Also, inheritance laws would not be in effect for the couple nor their children and they would lose any inheritance granted by the law at the death of a parent or spouse. The Church responded similarly. The Church would not recognize any civil marriage, since marriage was ordained of God and entrusted to Christ’s church on earth for protection.3 The Spanish people, caught between the two authorities, had to chose which they would follow. Those who chose to marry during the conflict showed their loyalties and true feelings greater than any who protested with words.

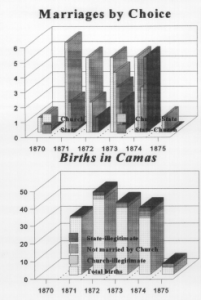

To best measure the choice of the people, I extracted their marriages from both the Civil Register and Church records. In Camas, Civil Registration begins in September 1870 continues through February 1875 when the conflict ends and then continues through today. Both records state the couples’ and parents’ names along with the date, place and time they are being married. The State’s records also list if the couple had previously married by the Church, whereas the Church’s do not acknowledge the previous marriage by the State. Therefore, I needed to consult both records to determine how many marriages had been performed yearly and where those marriages occurred (i.e., civilly and canonically or just civilly).’ These records shed light on which risks each family took or did not take. Forty-eight couples were married in the five year period. Each couple chose which power or powers they wished to follow, as can be seen on the marriage by choice chart. During those years eight couples married exclusively by the State authority, while sixteen married only by the Church. This leaves twenty-four couples who chose to marry by both.

One of the most important factors for each couple was the legitimacy of their children, A problem intensified by the State-Church conflict. Each parent knew the importance of inheritance rights and of the legal recognition of the State while at the same time they also wanted their offspring to be legitimate in the eyes of God. From the civil register of births and the Church’s records of baptism, we can learn a lot about their choices in the conflict. This choice perhaps more than any debate shows a persons true feelings and ideas. During the conflict years 146 children were born and registered in Camas. The Civil Register of births in Cainas lists five illegitimate children born during this time, two in 1872, one in 1873 and two in 1874, an average of one per year.5 Of those five, one from 1873 and one from 1874 are listed as legitimate births and the other three are also listed as illegitimate, upon examining the Church records.6 During the same time the Church records list three illegitimate births in addition to eight children born to “parents not married by the Church” (the way the Church had instructed the parish priests to inscribe those children born to civilly wedded parents).

The conflict between Church and State in Spain, represents a battle carried on not just between those in power on both sides but a battle that involved each of those that chose to marry and then have children during those conflictive years. The conflict represents a desire by a new constitutional State to exert its new control over the Spanish people at the expense of the Catholic Church and the age-old tradition of State and Religion going hand in hand. The Church refused to relinquish its control over marriage and legitimacy of children, citing the historical background of marriage, especially that God ordained marriage, Christ raised it to a Sacrament and then entrusted it to his Church on earth and the Church had never relinquished its control. The people of Spain heard the arguments, discussed their opinions, and, last of all, those who married during the conflict made their choice known. 17% chose the State exclusively, another 33% chose the Church exclusively, while the other 50% chose both sides. The more silent masses chose to be blessed by both the State and the Church, remaining the obedient subjects of both Church and State.

References

- Bahamode, Angel. Historia de España: España en democracia: El Sexenio, 1868-1874. Madrid: Ediciones Temas de Hoy, S.A., 1996, 64.

- Gomez Acebo, D. Manuel Marañon. Exámen del Decreto de 9 defebrero de 1875, Reformando la ley del matrimonio civil. Madrid, Imprenta de la revista de legislación, 1877, 12.

- Carrasco Baquero, José Toribio. Carta pastoral de Excmo. Señor Obispo de Lugo con motivo del llamado matrimonio civil. Lugo: Imprenta de Soto Freire, 1870, 4,6.

- Juzgado de Camas, Civil Register-Matrimonios, Camas, Sevilla, 1870-1875, v. 1-2. Iglesia Católica, Church Register-Matrimonios, Santa Maria de Gracia, Camas, Sevilla, 1870- 1875,v.6.

- Juzgado de Camas, Civil Register-Nacimientos, Camas, Sevilla, 1870-75, v. 1-7. Iglesia Católica, Church Register-Bautismos, Camas, Sevilla, 1870-75, v. 10.