Nikki Ricks

The purpose of this study is to examine differences in eye-tracking patterns between high and low risk groups of young adult women (based on the presence or absence of eating-disordered cognitions) using Scan Path Analysis. Recently, the BYU Communication Research Center purchased eye-tracking equipment from Applied Science Laboratories in Boston, MA. This equipment allows researchers to measure eye-movements in milliseconds across both still and dynamic images in real time. Data include not only the scan path or actual gaze trail, but also fixations (points of pause) and pupil expansion.

Social Problem

“Deep down inside, I still want to be a supermodel… As long as they’re there, screaming at me from the television, glaring at me from magazines, I’m stuck in the model trap. Hate them first. Then grow to like them. Love them. Emulate them. Die to be them. All the while praying this cycle will come to an end,” (Martin & Gentry, 1997, 3). Praise goes to those supermodels that are held up. That praise mixed with an envious gaze of the desire to become more and more like the image, one is going through the comparison of oneself. Leo Festinger stated “…in humans there exists a drive to evaluate his opinions and abilities by comparison with the opinions and abilities of others” (Leo Festinger, 1954). In the case of the above quote, to create a juxtaposition of what reality is and what the image portrays has a great possibility of resulting dangers to oneself.

A substantial body of literature has explored the impact of exposure to ultra-thin images in women’s fashion, beauty, and fitness magazines and issues related to body image disturbance and disordered eating (Martin & Gentry, 1997; Paxton & Durkin, 1999; Irving, 1990; Shaw, 1995; Thomsen, McCoy, Gustafson, & Williams, 2001; Thomsen, Weber, & Brown, 2001; Waller, Hamilton, & Shaw, 1992;). Most of this research is correlational in nature and relies on self-report data to assess the affects of reading and viewing ads and photographs contained in this genre of magazine targeted to a specific audience.

Recently, the BYU Communication Research Center purchased eye-tracking equipment from Applied Science Laboratories in Boston, MA. Eye-tracking equipment allows researchers to measure eye-movements in milliseconds across both still and dynamic images in real time. Data include not only the scan path or actual gaze trail, but also fixations (points of pause) and pupil expansion and contraction (which are an indication of physiological excitation or reaction). With this technology we anticipate a more accurate result.

Literature Review

The theory I intend to use is the Social Comparison Theory proposed by Leon Festinger in 1954. This theory states that the organization of cognitive information includes an assessment of how our ideas, opinions, characteristics/traits, and attributes match up against the desired ideals of important referent groups. These comparisons can be conscious or unconscious. Our self-concept is how we recognize ourselves physically, socially, emotionally, vocationally and so forth. The feedback we receive plays an important role in forming self-concept and identity development.

Comparison, evaluation, improvement, or enhancement may occur, through this process of development. “Few studies have explicitly examined the ways in which mass media promote the view that what is thin is good. However, this message may be subtly conveyed by the absence of females who deviate from the thin ideal in electronic and print media. For example, Silverstein et al. (1986) reported that only 5% of actresses in recurring roles on television were classified as heavy in comparison to 25.5% of actors” (Morrison, 2004, 573). With this significant difference in percentages between male and female the correlation between females containing a greater likelihood of eating disorders is confirmed. If we take what the social theory proposes and with comparison, evaluation, improvement, or enhancement of the viewer many consequences are at stake, positive and negative. This is interesting considering that one study showed that adolescents have greater body dissatisfaction after viewing images (Shaw 1995). Media holds a standard in which society has deemed the ideal. These images that adolescents compare themselves to, are from societies established referent groups. It is interesting to note when and how strongly these adolescent internalize these body images into personal schema. These image body types in advertising represent a small amount of the realistic population.

Advertising viewing may or may not have an effect on the attitudes of those that view; though studies have shown that attitudes have eventually led to effect behavior. In a study conducted by Dittmar, “75% of the females in their study had the combinations of either low comparison to the images of thin model, but high internalization, or high comparison to the images of thin models with low internalization” (Dittmar, 2004, 787). Magazine reading is related to concerns of appearance and eating behaviors. For someone to go from desire to a behavior from the cause of reading a magazine is substantial. Though reading this may result in change for healthy eating and exercise the likelihood is just the opposite, eating disorders. All for the shear reason of comparison and desire to measure up to that image that is being viewed.

The comparisons that humans make, directly is self-evaluation through the social comparison processes. It seems possible that individuals making low concluding judgment concerning life events also feel that the problems they are dealing with are unique or different, as if no one else has experienced that kind of feeling or emotion (Furnham 2001). A study was conducted on a group of adolescent female volleyball players comparing their physical self-concept of the images in women’s health, fitness, and sports magazines. The group during the process of viewing images would refer to the different parts of the body of the women and the way in which they were portrayed as a specific group of women, being athletes. A large portion of the females expressed their personal comparison to the images in the magazine, as well as comparison to those girls who are not athletes. These women not only compare themselves to images of athletes in magazines but also to models. A concern was the balance between the two-referent groups, considering the fact that they were in two different worlds of ideal body image (Thomsen, McCoy, Gustafson, & Williams, 2001).

Upward and Downward comparison are two comparisons in which one may compare to others or groups that are superior (upward) or inferior (downward). Upward comparison is that of comparing oneself to someone who is judged better on a dimension of importance to improve. A danger of this type of comparison is that they may become threatening because they are close to one’s own “low standard”. Downward comparison is also threatening to self-image because it is the resort of comparison of a group that is inferior for augmentation of oneself. To use upward and downward comparison an initial concern or discomfort has to exist. Because of this existing insecurity the comparison occurs.

Martin and Gentry (1997) studied the self-evaluation motive, self-improvement motive, self-enhancement motive through downward comparison, self-enhancement motive through discounting the beauty of the models, and general motives (control group) among fourth, sixth, and eighth graders. The results were that motives do play an important role; they affect the want for change in all aspects of self-perception of physical attractiveness, body image, and self-esteem. In accordance with most studies done on social comparison, females’ self-perception and self-esteem can be destructive, in particularly when self-evaluation of oneself occurs. One positive finding was that the addition of motives shows that hurtful effects do not always occur. That is, positive temporary effects occur when either self-improvement or self-enhancement is the motive for comparison: self-perceptions of physical attractiveness were raised in subjects who self-improved or self-enhanced through downward comparisons. Self-perceptions and self-esteem were unaffected in most cases in subjects who self enhanced by discounting the beauty of models. However there is the exception of the occurrence of the sixth graders’ self-perceptions of body image was heightened (Martin & Gentry, 1997). Advertisements hold a great power in the way social comparison occurs and is then transferred to self-perception.

Irving used social comparison theory to observe females that were suffering from eating disorders. Irving concluded that exposure to thin models in advertising was related to lower self-evaluations regardless of the level of bulimic symptoms (Irving, 1990). For both men and women who fitness magazines have a greater concern to self-image and have a higher likelihood to show eating disorder, then those who do not.

Thin model figures are shown in all types of media and affect all groups of women whether they have an eating disorder, are on the verge of one, or are perfectly healthy. From advertising in magazines to television, it would be hard to not be exposed. Drawing from these results one question that may be posed is the content of the advertisement worth having the images all together. The intention of the advertisement is interesting to observe, is it to encourage consumption of the good or service? An intelligent advertising campaign targets an audience and researches the results there of. How, why, do these images, these advertisement have the strong effect on schema that they do?

For women to have these abrasive images in their daily view, one cannot help, with the theory of Festinger, to compare ones self to these images. This comparison is natural and apart of human behavior. There is a difference however having the ideal be internalized into a personal belief or simply being aware of the importance of appearance and thinness that lays in our society. Majority of the women who are comparing themselves to the cultural ideal body image are over weight or not comparable to the weight that the image portrays. While comparing oneself in general may be a negative exercise, its detrimental effects may be magnified when comparing oneself to a societal referent groups that is judged to be more important to the subject. The insecurities that may occur in our lives may be magnified by the social comparison process. To want more and to contain the desire to become something else become of low self-perception or low self-esteem is a concerning matter.

All of these studies above however are qualitative in their research. Ideally with the eye-tracking technology we will be able to draw scientific, quantitative data with the physiological reaction to the advertisements. With this study, we anticipate that with the eye tracking technology it will conduct a more accurate result of the impact of that the images contain and convey to the viewers of those advertisements.

Hypotheses

1) During the viewing of ultra-thin super models there a positive correlation with the eye fixations of high risk women.

2) High risk women will spend a greater percentage of scan time then low risk women in specific look zones such as the neck, stomach, and inner thigh.

Methodology

Sample

A convenience sample of 22 women will be obtained through personal connections on the BYU campus.

IRB

Appropriate documents will be submitted to the BYU IRB after the granting of the ORCA office. Only those women who sign the required consent forms will be allowed to participate in the study. Procedure. In the first phase of the project, I will administer the Mizes Anorexic Cognitions Scale (MACS) to all the participants. The MACS is a 33-item scale that measures the internalization of pathological beliefs and values associated with eating disorders (e.g., anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa). High scores are indicative of disordered thinking and high levels of risk in non-clinical or non-diagnosed populations. Using a median split technique, the participants will be split into two groups (high risk and low risk) for post-hoc comparisons once data from eye tracker and the MACS test all the subjects have been collected.

In the second phase of the project, the participants will come to the eye-tracking lab where the Scan Path Analysis will take place. The women will come one at a time. The current lab setup only accommodates one participant at a time and takes quite a bit of preparation. They will be given an overview of the equipment and will then be fitted with the head-mounted integrated optical device used in the tracking and scanning process. The device is worn on the head (much like a visor or hat) and causes no physical discomfort or strain. We will allow adequate time for the participants to become comfortable with the equipment; this also serves the purpose of reducing any obtrusiveness.

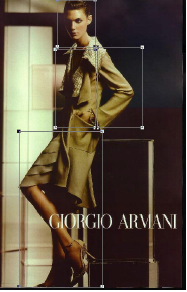

At this point, each participant will be shown a series of photographic images from women’s beauty, fashion and fitness magazines that have been scanned onto a “source” computer. Also other “placebo” advertisements will be inserted to keep initial reaction to the women’s beauty, fashion and fitness magazine advertisements significant. Throughout this process eye-tracking and pupil reaction data will be collected.

Analysis

Once all data have been collected from each participant, post-hoc comparisons (between the high risk and low risk groups) will be made. Specifically, we will make between-group comparisons of the fixation and gaze times for specific look zones (body parts and/or areas of the photographic images such as: neck, arms, and thighs) as well as average changes in pupil diameter for specific regions. In so doing to therefore determine if a significant difference exists in arousal levels between the separate groups of high and low eating disorders, and concluding that women may or may not have a psychological reaction to body image in advertising.

Results

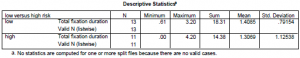

To create our groups for comparison, we summed the 33 items from the Mizes Anorectic Cognitions Scale. The scale produces a score that ranges from 33 to 165. The higher the score the greater the risk, as measured by the presence of anorexic cognitions. We then split the subjects into two groups (high risk and low risk). We calculated the median for the total MACS score and then split the groups: those who scored at or below the median were placed in the low risk group; those who scored above the median were placed in the high risk group. Overall, however, our 22 subjects had relatively low total MACS scores (M = 68.34, SD = 21.07).

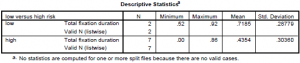

As can be seen in the table above, the high risk group(M=22.48 SD= 8.25, M=25.28, SD=10.86) actually spent slightly less time fixating on the beauty and fashion ads than the low risk group. The data above represents the mean fixation times for all ads combined.

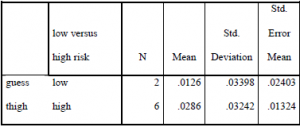

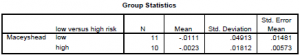

We then examined the differences in fixation duration and net change in pupil diameter for each subject, for the space between the inner thighs look zone for the Guess ad. Of the 22 girls we tracked, 8 had at least one fixation in the look zone we created for the space between the inner thighs. Of the 9 who had at least one fixation, 7 were in our high risk group and 2 were in the low risk group.

As can be seen in the data table above, the low risk group (M = .71, SD = .28) actually spent slightly more time fixating in the inner thighs look zone than the high risk group (M = .43, SD = .3), which was the opposite of what we had hypothesized.

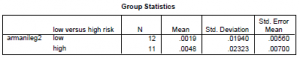

Group Statistics

When we compared net change in pupil diameter, however, we found that the net change was substantially greater for high risk group (M = .02, SD = .03) than for the low risk group (M = .01, SD = .03), which is what we had anticipated. This suggests that although the high risk group spent less time looking at the space between the inner thighs they, nonetheless, had a much stronger physiological reaction. Pupil diameter change also is an indication of cognitive load, suggesting that the high risk group was making a greater effort to process the information than the low risk group.

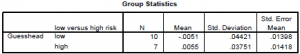

The same was done for the Guess Head/Neck look zone and the pupil expansion for high risk group (M= .005, SD .03) became greater than for the low risk group (M= -.005, SD .04).

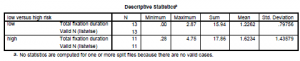

As can be seen in the table above 13 subjects were in the low risk group, and 11 subjects in the high risk group. The high risk group (M=1.3 SD=1.12) had a slightly smaller fixation duration in the Macy’s Head/Neck look zone then the low risk group (M=1.4 SD= .79).

The above chart compared net change in pupil diameter, for the Macy’s Head/Neck look zone, we found that the net change was greater for high risk group (M = .0048, SD = .0019) than for the low risk group (M = 1.22, SD = .79).

As can be seen in the table above 13 subjects were in the low risk group, and 11 subjects in the high risk group. The high risk group (M=1.62 SD=1.43) had a longer fixation duration in the Armani leg look zone then the low risk group (M=1.22 SD= .79).

The above chart compared net change in pupil diameter, for the Armani leg look zone, we found that the net change was substantially greater for high risk group (M = .0048, SD = .0019) than for the low risk group (M = 1.22, SD = .79).

Discussion

This study obviously did not hold the power of sample size, but we did find some interesting patterns. As our findings were not consistent with our hypothesis, we see this due to Cognitive Dissonance Theory suggesting that the perception of incompatibility between two cognitions, which can be defined as any element of knowledge, including attitude, emotion, belief, or behavior. The theory of cognitive dissonance holds that contradicting cognitions serve as a driving force that compels the mind to acquire or invent new thoughts or beliefs, or to modify existing beliefs, so as to reduce the amount of dissonance (conflict) between cognitions. The cognitions, in this case, are the look zones on the women in the advertising images. The indicator of this is the findings of the fixation times and the pupil diameter increase. Pupil diameter change also is an indication of cognitive load, suggesting that the high risk group was making a greater effort to process the information than the low risk group.

It is good to note for future study to see the look zones in trying to be as clear as possible, with no text within the look zone; as text could be included as a fixation as opposed to a body fixation.

Conclusion

Through this study we have found that pupil fluctuation and rating of eating disorder risk are positively correlated; therefore because pupil diameter increases this showed an interest of the subject. From this we can say that a high rating of eating disorder a larger increase of pupil may be found.

Bibliography

- Dittmar, H., & Howard, S., (2004). Thin-Ideal Internalization and Social Comparison Tendency As Moderatorrs of Media Model’s Impact on Women’s Body-Focused Anxiety. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology. 23 (6), 768 – 791.

- Festinger Leon, A Theory of Social Comparison Processes. Human

Relations 7 (February 1954): 117-40. - Furnham, Adrian, Social Comparison and Depression. Journal of Genetic Psychology 149 (2001): 191-198

- Irving, L. M. (1990). Mirror images: Effects of the standard of the standard of beauty of the self- and body-esteem of women exhibiting varying levels of bulimic symptoms. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 9 (2), 230-242.

- Martin, C. & Gentry, J. (1997). Stuck in the model trap: The effects of beautiful models in ads on female pre-adolescents and adolescents. Journal of Advertising, 26 (2), 19-33.

- Morrison, T. G., Kalin, R, & Morrison, M. A., (Fall 2004). Body-Image Evaluation and Body-Image Investment Among Adolescents: A Test of Sociocultural and Social Comparison Theories

- Paxton, S. & Durkin, S. (1999, April). Predictors of response to a brief presentation of advertising images in adolescent girls. A paper presented at the Fourth London International Conference on Eating Disorders, London, UK.

vShaw, J. (1995). Effects of fashion magazines on body dissatisfaction and eating psychopathology in adolescent and adult females. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 3 (1), 15-23. - Silverstein, B., Perdue, L., Peterson, B., & Kelly, E. (1986). The role of the

mass media in promoting a thin standard of bodily attractiveness for

women. Sex Roles, 14, 519-533. - Thomsen, S.R., McCoy, J.K., & Williams, M. (2001). Internalizing the impossible: Anorexic outpatients’ experiences with women’s beauty and fashion magazines, Eating Disorders, 9(1):49-64.

- Thomsen, S. R., Weber, M., & Brown, L. B. (2001). Health and Fitness Magazine Reading and Eating-Disordered Diet Practices Among High School Girls. American Journal of Health Education, May/June, 32(3): 130-135.

- Waller, G., Hamilton, K., & Shaw, J. (1992). Media influences on body size estimation in eating disordered and comparison subjects. British Review of Bulimia and Anorexia Nervosa, 6 (2), 81-87.