Chris M. Wilson and Dr. E. Vance Randall, Secondary Education

Since the landmark case of Brown v. The Board of Education (1954) there has been a continual stream of educational finance equity litigation. The focus of these court cases is the equitable allocation of resources from the state and from local sources (Larson 1990). “Equity” has conventionally been examined only by considering traditional sources of revenue (e.g., property tax, income tax, weighted pupil unit money). This study has expanded the scope of inquiry into the school equity issue by examining non-traditional sources (e.g., business partnerships, private foundations, donated services, and user fees). Analyzing non-traditional resources flowing into one urban and one rural district in Utah expose several equity questions.

The total dollar amount of resources injected into district funds constituted only a minor percentage of the total yearly budgets of the districts. $2,527,178 dollars were captured by the 76 schools in the urban district. The 9 rural district schools collected $27,244 dollars of non-traditional sources. The dollar per pupil mean between the urban and rural district was similar. The urban district mean was $47.14 per pupil; the rural district mean was $55.18 per student. It appears that on a district level, non-traditional resources are not causing any significant equity disparity. Analysis between individual schools within a district does reveal an equity concern. The range within the individual schools of the urban district extended from a low of $0.00 to a high of $797.46 per pupil. $797.46 represented 47.7% of the weighted pupil unit (the primary traditional source of revenue). If every student within one school receives $797.46 more than students at another school, the equal educational opportunity principle set down by Brown v. The Board of Education (1954) is threatened. Likewise, within the schools of the rural district a similar disparity exists. The range for the rural schools was $0.00 to $141.93 per pupil. This is a much smaller disparity between schools than was found in the urban district, but again significant to the educational opportunity for students. Next, comparing the leading rural school’s $141.93 against the leading urban school’s $797.46 shows substantial inequity in the ability for individual rural schools to capture amounts comparable with the urban schools.

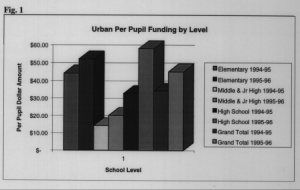

The data from this study also shows some important trends of the flow of non-traditional resources among school levels. Elementary and high schools in the urban district receive more money than do middle and junior high schools (Fig. 1). It is common knowledge that parents and the community are more involved with their children’s education at the elementary and high school levels. The amount of funding captured from non-traditional sources seems to support that conclusion. However, one alternative explanation is that middle and junior high schools do not place the same emphasis on soliciting these nontraditional resources because of other more pressing concerns, such as school discipline. This information could heighten the awareness of middle and junior high school administrations to the opportunity for capturing much needed funds through nontraditional channels.

This study also examined the origins of the non-traditional resources. The five categories of nontraditional resources adapted from Meno (1984) are-. 1) Donor Resources, 2) Enterprise Resources, 3) Cooperative Resources, 4) Cooperative Resources with other Government Agencies, and 5) Cooperative Resources with Business and Industry. Among these five resource categories in the urban district, Donor Resources were by far the largest contributor while Enterprise Resources came next. Elementary schools used Donor Resources as their primary source of non-traditional funding while high schools captured principally Enterprise Resources through club fund raising. The rural schools also procured primarily Donor Resources. Cooperative Resources, in contrast, fell second among the five categories of funding for the rural district.

Since it is likely that non-traditional funding of public schools will only continue to grow in the future, it is important for educators to understand the impact this growth will have. As we see in this study the non-traditional resources flow to individual schools in inequitable degrees. This gap is likely to only increase in the future. Also, rural schools are not keeping pace with urban schools in capturing non-traditional resources. Middle and junior high schools are likewise faltering in obtaining non-traditional funding.

References

- Larson, L. (1990). State School Finance Litigation: A Background Paper. (Eric Document Reproduction Service No. ED 355791.

- Meno, L. R. (1984). Sources ofalternative Revenue. In Fifth Annual Yearbook of Education Finance, edited by L.D. Webb and V. D. Mueller. Cambridge: Ballinger.