Christine H. Walton, Neuroscience

Previous neurological studies have found the degree of environmental complexity influences the acquisition and development of motor skills in human infants as well as animal models. During a critical period in human development, which is believed to span the first 6-10 years for human visual-motor development, neurons grow and solidify appropriate connections. Signals sent from cell to cell are insulated by additional protective cells in a process called myelination. These postnatal cognitive developments are influenced by sensory input and experience. It appears that deprivation of appropriate stimuli in a subject’s surroundings at this time results in decreased cognitive development as inferred by a trend of decreased performance in various neurological examinations. This study analyzed the performance of 74 south-Indian children from varying socioeconomic backgrounds between the ages of 5 and 6 on the Bender Gestalt and Rey-Osterrieth Complex Figure drawing and copying tasks. Scores were then compared to the number of toys available in the household. Results show a small positive correlation between the number of toys and performance on the drawing and copying tasks. Latent variables are still present in the data and merit further investigation of these results.

Neuroplasticity in the Early Years

The first years of life are a period of enormous evolutionary dynamism in children as myelination and maturation of association areas in the brain occurs [18]. This brain maturation is manifested in the development of the child’s motor function (for example, progression from grasping to rolling over, sitting up, and so on) among other things. As myelination and maturation occur during this critical period, practice of motor function subsequently influences said myelination and the structural organization of the nervous system [18]. The child’s potential for his or her motor development is therefore influenced by both genetic and environmental factors.

Factors of Influence

These environmental factors include the presence of a father, mother, education, use of proper or improper toys at a certain age, the residence of the child during infancy, and socioeconomic status of the family [18]. Individuals who spend their formative years in areas where insufficient or inappropriate environmental stimulation is available would have less practice with grasping and manipulating objects in space and therefore underdeveloped visual-motor association areas in the brain. Research in human children has shown that the presence of tables, chairs, and other environmental anchors aid infant motor development through this cognitive maturation process [14]. The presence of toys has also been shown to facilitate the psychosocial development of a child [10]. Higher motor processing and the integration of information from the surroundings must be influenced by increased environmental complexity and the subsequent exposure to new objects that may be manipulated by the child; toys are a key example. For example, further studies of infants reveal a delay in motor development in 12 month and older Yucatecan infants when compared to USA infants of the same age [14]. The delay in motor ability was attributed to the decreased environmental complexity of Yucatecan homes.

Latent Variables

It is important to note that the presence of complex objects in the environment is not the only source of cognitive stimulation toddlers receive. Mother’s education, the presence of a father, quality of parental care, genetics, socioeconomic status, and childhood health and nutrition all have a significant influence on the cognitive development of children [8]. A means of controlling for these variables is required to verify that the complexity of the environment is the only variable influencing motor development in the child.

Research Site

According to the 2005 Tamil Nadu Human Development Report, 22.5% of the population in Coimbatore, India, lives below the poverty line. As distance from the city increases, the number of families living below the poverty line increases as well. These families struggle to find enough money to put food on the table, much less worry about the amount or type of toys available to their children.

Collecting data in this socioeconomic backdrop allowed significant variance in access to toys or similar environmental stimuli.

Materials and Methods

Subjects

Thirty-six females and thirty-nine males between the ages of 5 and 6 participated in this study, with the written consent of a parent or guardian. No neurological or physical disabilities were observed.

Of the 75 subjects, 18 lived below poverty line with no educational support, 27 lived below poverty line but had received preschool instruction and nutritional supplementation by a local non-government organization, and 30 subjects came from families who reported incomes significantly above the poverty line.

Test Background

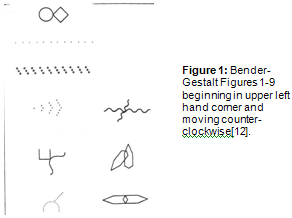

The Bender-Gestalt Test has been one of the first and most widely studied drawing tests in neuropsychological assessment [12]. It consists of 9 geometric figures (Fig 1) each of which the subject is asked to copy on a sheet of blank, white paper. Its initial use was to study visuoperceptual and visuomotor development in children, but has since been used to measure cognitive growth in cases of behavioral disorders such as schizophrenia.

The Rey Complex Figure Test is a versatile examination that has been used to effectively assess perceptual organization as well as visual memory in subjects in a very wide age range.

Constructional activities like these copying tasks will integrate both the child’s visual and spatial perceptions and motor response [12].

Testing Procedure

Tests were administered in classrooms provided by the local school at six different locations. Typically, groups of ten children were asked to sit cross-legged on the floor and were each given a sharpened #2 pencil with an eraser.

A stack of ten sheets of 8.5’’ x 11’’ white printer paper was set in front of each child, oriented with the long edge pointing to the front of the room. The test administrator held 11’’ x 17’’ cards, each depicting one Bender Gestalt figure. Children were instructed to copy the image they saw onto the paper.

No direction was given as to how many figures to put on each page. Administrators moved to the next figure only once all the children had completed the copy to their satisfaction. All 9 Bender Gestalt figures were displayed in the same order for each group.

Once the subjects had completed the Figure 9, they were instructed to sit still while pencils were collected. They were then each given a set of 9 colored pencils, and instructed to draw what they saw with first the red, then blue, green, orange, black, and purple colors while the administrator displayed the Rey-Osterrieth Complex figure. Every 60 seconds the child was asked to change to the next indicated color, allowing 6 minutes total to copy the entire figure.

Scoring Procedure

Tests were scored using the “Qualitative Scoring System for the Modified Bender-Gestalt Test” by Brannigan [5] and the scoring protocol outlined by Koppitz [9]. Rey-Osterrieth Complex figure scores were ascertained using the protocol found in Lezak [12].

Interviewing

The mother or guardian of each child was contacted by the test administrator with the assistance of a translator. Written consent was obtained on translated consent forms prior to initiation of the interview.

Interviews were semi-structured, with a base of 9 questions related to the child’s health history, play-habits, and available toys as well as the mother’s education and attitude about recreation and play.

Digital photos were taken of the room (Fig 2) in which the child spent the majority of his or her time, as well as his or her 5 favorite toys (Fig 3). In some instances, 5 toys were not available.

Data Analysis

Latent variables were kept as constant as possible throughout data collection. However, their presence still may influence the data. Additional data analysis beyond the results shown in this paper is required to normalize the data and control for variance in nutrition, mother’s education, and household size.

Results

Bender-Gestalt Test

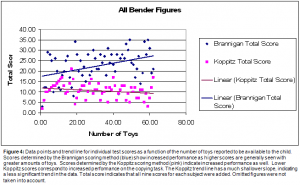

High levels variation were observed in the relationship between performance on the Bender-Gestalt figure copying task and the number of toys in the home according to the Brannigan and Koppitz scoring systems.

Koppitz scores per figure (not shown) do not deviate significantly as number of toys in the home increases. However, when these scores are totaled for each subject, a weak but detectable trend is seen with increased toy presence and improved performance on the Bender-Gestalt test (Fig 4).

Brannigan scores per figure (not shown) exhibit high variance, but trend lines show a consistent positive correlation between number of toys and test score. The same trend is observed when comparing total Brannigan scores between subjects (Fig 4).

Rey-Osterrieth Complex Figure

Scores for the Rey-Osterrieth complex figure appear to have decreased variance in subjects with less than 15 toys, and increasing variance in test scores past that point. However, total complex figure scores appear to be less random and follow the trend line more closely than do scores for the Bender-Gestalt Test.

There appears to be a weak but detectable positive correlation between number of toys and test performance (Fig 5).

Comparison by Grouping

Further data analysis was conducted by calculating average test scores once the subjects were divided into two groups: high toy presence (5 toys or greater) and low toy presence (less than 5 toys). Average test scores between the two groups appear to be statistically insignificant (not shown).

Percentage of children in each group receiving low scores (0-2), high scores (3-4), and exceptional scores (5) shows no significant difference in children achieving low and high scores between groups (Fig 6). However, there appears to be a significant increase in children receiving exceptional scores in the high group compared to the low group.

Discussion and Conclusion

Current Research

The positive trend lines seen in Figures 4-5 suggest a gradual improvement in test scores as the number of available toys increases. This is consistent with previous findings [6, 7, 10, 11, 18, 19].

Due to variance and the weakness of the trend, further statistical analysis and data retrieval is needed. Average scores for high and low toy groups reveal little about what is actually occurring in the population, as averages are greatly skewed by positive and negative deviations. The increased percentage of children in the high group achieving exceptional scores (Fig 6) indicates that increased toy presence may influence cognitive growth.

Future Research

It is highly likely that these early environmental influences are not based solely on toy presence. Even in BPL households, significant variance in environmental complexity exists. Different parenting styles, access to community toys, or creativity in construction of “home-made” toys all factor into environmental stimulation.

Inaccuracies in interpretation of the word “toy” also could have skewed data, and a standardized definition for “toy” is required before further research is conducted.

Sources

- Bender, Lauretta. A Visual Motor Gestalt Test and its Clinical Use. The American Orthopychiatric Association, Research Monographies No. 3. New York 1938.

- Bensur, Barbara Jean, U Maryland Coll Park, Us. Simultaneous developmental progression in children analyzed through the use of children’s drawings and five independent measures. Dissertation Abstracts International Section A: Humanities and Social Sciences, Vol 56(11-A), May 1996. pp 4254.

- Borooah, Vani K. Births, Infants and children: An Economic Portrait of Women and Children in India. Development and Change, 2003, 24, 1, Jan, 67-103.

- Bose, A.B.; Saxena, P.C. Some characteristics of the child population in rural society. Journal of Family Welfare, 12(1), 1965. pp.12-23.

- Brannigan, Gary G; Brunner, Nancy A. Guide to the Qualitative Scoring System for the Modified Version of the Bender Gestalt Test. Charles C Thomas Publisher, Ltd. Illinois, 2002.

- Chan, P.W. Relationship of Visual Motor Development and Academic Performance of Young Children in Hong Kong. Percept Motor Skills. 2000 Feb; 90(1), pp.209-14.

- Demsky, Yvonne; Carone, Dominic A; Burns, William J; Sellers, Alfred. Assessment of Visual Motor Coordination in 6 to 11 year olds. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 2000, 91, 311-321.

- Guo, Guang; Harris, Kathleen M. The Mechanisms Mediating the Effects of Poverty on Children’s Intellectual Development. Demography, Vol 37 (4) Nov 2000 pp 431-446.

- Koppitz, Elizabeth M. The Bender Gestalt Test for Young Children. Vol. 2. Gurne and Stratton, Inc. New York, 1975.

- Kumar R; Agarwal AK; Kaur M; Iyengar SD. Factors influencing psychosocial development of preschool children in a rural area of Haryana, India. Journal of Tropical Pediatrics 1997 Dec; Vol. 43 (6), pp. 324-9.

- Leggio, M., Mandolesi, L., Fredrico, P., Spirito, F. Ricci, B., Gelfo, F. Petrosini, L. Environmental enrichment promotes improved spatial abilities and enhanced dendritic growth in the rat. Behavioral Brain Research 2005 Aug 30; Vol. 163 (1), pp. 78-90.

- Lezak, Muriel D. and Diane B. Howieson, David W. Loring. Neuropsychological Assessment: 4th Edition. New York, New York; Oxford University Press, 2004.

- Park, Rosemarie J., Harvard U. Performance on geometric figure-copying tests as predictors of types of errors in decoding. Dissertation Abstracts International, Vol 37(6-A), Dec 1976. pp. 3399-3400

- Solomons, G., Solomons, H.C. Motor Development in Yucatecan Infants. Developmental Medicine and Child Neurology. 1975 Feb; 17(1), pp. 41-6.

- Solomons, G; Solomons, H.C. Factors Affecting Motor Performance in Four-Month-Old Infants. Child Development [Child Dev] 1964 Dec; Vol. 35, pp. 1283-95.

- Rani, N. Indira. Child Care by Poor Single Mothers: Study of Mother-Headed Families in India. Journal of Comparative Family Studies; Winter 2006, Vol. 37 Issue 1, p75-91, 17p.

- Vasvi, A. R. Schooling for a New Society? The Social and Political Bases of Education Deprivation in India. IDS Bulletin, vol. 34, no. 1, pp. 72, Jan 2003

- de Barros, KMFT, Fragoso AGC, de Oliveira ALB, Cabral JE, de Castro RM. Do environmental influences alter motor abilities acquisition? A comparison among children from day-car centers and private schools. Arquivos de Neuro-psiquiatria 61 (2A): 170-175 June 2003.

- Gunnar, Megan R. Effects of Early Deprivation: Findings from Orphanage-Reared Infants and Children. Handbook of Developmental Cognitive Neuroscience, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 2001. pp 617-29.