Christopher Palmer and Dr. Frank McIntyre, Economics Department

This paper employs microdata from the 2001 Armenian National Census to consider how varying levels of higher education affect the likelihood that an individual is employed in Armenia. The analysis concludes that the effect of incomplete undergraduate education on employment status is not statistically different from the effect of terminating one’s education after graduating high school. I consider several theoretical improvements on the standard probit and logit models using an instrumental variables approach and flexible distributions. Armenia is an interesting case study of economic contrasts. While Armenia’s double-digit economic growth suggests that it is adapting to the new market economy, some sources put Armenia’s unemployment rate as recently as 2004 at a staggering 31.4%. Higher education does not appear to help with mobility: a 2001 UNDP report classified as poor 50% of Armenians with higher education. Quantifying the lack of benefits of college education should motivate further reform to prepare Armenian students for specialized employment opportunities upon graduation.

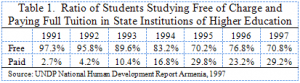

n 1996 the majority of the nearly 25% of the registered unemployed looking for work for the first time were recent graduates of Armenian institutions of higher learning (UNDP 1997). A 2001 UNDP report found that in 2001, 1,154 teachers, 1,161 lawyers, and 503 artists received degrees from institutions of higher learning in Armenia. As context for the aforementioned figures, consider that according to Freedom House (2000) there were less than 900 licensed lawyers nationwide in 1999. Barring an implausible increase in the demand for legal services, the Armenian economy simply cannot employ the vast majority of these college graduates. The UNDP study concludes, “The majority of these young people have few realistic chances to work in these professions in the near future. As to the inadequacy of the knowledge, skills and the demands of the market… only 12% assessed their chances as high for meeting market competition” (UNDP 2001). Nevertheless, the survey did find that the rising generation in Armenia is more inclined than their predecessors to consider the marketability of a given degree in making decisions about education investment. Additionally, while Armenia has historically provided higher education at nearly no cost to the overwhelming majority of eligible students, the fraction of students attending state institutions and paying their own expenses is growing (Table 1).

Reduction in the state subsidies to college students should help eliminate free-riders that may be attending school to avoid compulsory military service or delay entering a weak labor market.

I use a binary response model to estimate the effect of highest level of education attained on the likelihood an individual is employed, as shown below:

where work is 1 if individual t is employed and 0 otherwise. F(·) denotes the cumulative density function of several different distributions. The variables advdegree, college, somecoll, tech, and hs encapsulate whether an individual’s highest education level is advanced degree, college degree, partial college attendance, technical school graduation or high school graduation, respectively. The variable welfare takes on 1 if the individual is currently receiving state welfare and 0 otherwise, and all remaining variables are self-explanatory. As the Census did not record any physical characteristics, I use welfare to control for an individual’s ability to participate in the labor force. However, as employment status is also an explanatory factor of receipt of welfare, I model welfare separately and use a two-stage approach to control for simultaneity bias.

My results suggest that that incomplete higher education does not increase an individual’s chance of being employed, while graduation from college or an advance degree program does significantly improve the likelihood an individual is employed. These results should alarm higher education administrators in Armenia. Apparently, private educational institutions have been quicker to react to market incentives and develop courses of study that actually enhance the marketability of graduates, but have suffered from reputation issues as they struggle to gain respected faculty and students against the strong state subsidization of a few public universities (NHDP, 1997). As transition proceeds, parents making decisions about whether to invest in additional schooling for their children should be informed that, from the standpoint of finding work, an incomplete college education or graduation from a technical school does not improve the likelihood their children will be employed any more than merely graduating from public secondary school.

Policymakers in Armenia should take measures to liberalize the higher education system in Armenia. Men attending private universities should be able to defer compulsory military service as easily as men attending public universities. As the disparity between the treatment of private and public institutions by the government diminishes, state-subsidized public universities will have to compete with private institutions for students on the basis of value-added to the student. Competition will encourage public institutions to react to market forces in developing curricula that have real economic benefit to graduates.

There are many extensions to this paper possible. More research into the relationship between welfare and measures of permanent wealth and financial need would reduce the probability of misspecification in the first stage of the structural equation that governs welfare. A heteroskedastic probit model has theoretical promise, owing to the high number of binary variables in the model. Attempts to model the qualitative response with a more flexible distribution, such as the Skewed Generalized-t, which allows for varying skewness and kurtosis, also has potential.

Next, UNDP research (2001) suggests that being employed in Armenia may be a misleading indication of economic well-being. Even among the employed, 17% were classified as extremely poor in 2001. Accordingly, predicting the probability of employment during one arbitrary week of the year is undeniably limited in its usefulness. This summer I met with the Armenian National Statistical Service in Armenia to obtain Household Living Standards Survey data which has both the housing characteristics such as heating type, presence of plumbing, etc., present in the 2001 Census data set and a continuous measure of income. I am currently using the Living Standards Survey data study the returns to education on income in conjunction with my Honors Thesis.

References

- Education, Poverty and Economic Activity. United Nationals Development Programme Survey, 2001. Retrieved April 10, 2007.http://www.undp.am/docs/publications/publications-archive/nhdr01/main.phpl=en&chapter=3&id=3_5

- Freedom House. Nations in Transit 1999-2000: Country Report of Armenia.

- National Human Development Report Armenia 1997: Social Cohesion. United Nations Development Programme.