Eve Okura and Dr. Cynthia Hallen, Linguistics

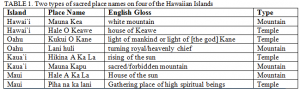

In cultures with oral traditions, sacred place names and ritual language may serve as a sacred text of a people. Cultures across the globe have unique definitions of and rules reagrding sacred space. Knowing these rules and definitions can help the cross-cultural traveler exhibit more culturally sensitive behavior in other lands. The benefits of this are many, including but not limited to avoiding unintentional offence, gaining respect of the people, and perhaps even obtaining insight into deeper cultural concepts that may enhance one’s own experience of the sacred. Hawaiian sacred place names and ritual language teach some of these. Native Hawaiian sacred place names and ritual language also reveal how Hawai`i fits in to the global pattern of traditional concepts and practices regarding sacred space. In Hawaiian, the term for a sacred place is wahi pana. Wahi is the word for place. In isolation, the word pana means “pulse.” Thus, sacred places are “places with a pulse,” living space. In this research I used Mircea Eliade’s definition of the term “sacred.” Not only does he define the sacred, but he also explains why knowledge of the sacred is important: The sacred is equivalent to a power, and, in the last analysis, to reality. The sacred is saturated with being. Sacred power means reality and at the same time enduringness and efficacity. The polarity sacred-profane is often expressed as an opposition between real and unreal or pseudoreal…. Thus it is easy to understand that religious man deeply desires to be, to participate in reality, to be saturated with power. (Eliade, Sacred and Profane 13) According to Eliade, to understand the sacred is to understand existence, because sacred space replicates prototypical space, the “real” space, where humans dwelt, in the presence of the gods, before humanity “fell.” Such space represents the paradisiacal realm to which humans yearn to return. Thus the recognition of the sacred and the visiting of sacred sites is a quest to experience a “true reality,” which is associated with divine power. We see this even in Latter-day Saint theology, because the temple (a sacred place) is equated with a bestowal of power: “Yea, verily I say unto you, I gave unto you a commandment that you should build a house, in the which house I design to endow those whom I have chosen with power from on high” (Doctrine and Covenants 95:8). The journey through a Latter-day Saint temple represents a fall from the presence of God, and a return to our heavenly “home.” The construction of a temple is the demarcation of sacred space, as is also the construction of a “house.” It is through these precincts that the heavens, both primeval and post-mortal, can be accessed for sacred power. In his essays in Temple and Cosmos, Hugh Nibley notes that divisions of social space are often laid out in orientation to a central sacred locale. This sacred space, or navel, as he calls it, appears as a symbol of sacred space in the ancient Near Eastern. The temple…is the hierocentric point around which all things are organized. It is the omphalos (“navel”) around which the earth was organized. The temple is a scale model of the universe, boxed to the compass, a very important feature of every town in our contemporary civilization, as in the ancient world. (Nibley 15) Sacred places then serve not only as a spiritual compass, but as a center point around which civilization is oriented. This is true of the temple in Jerusalem and the Latter-day Saint temple in Salt Lake City, which is literally serves as the center for the grid-layout of the city. In my research I found this to be true on the Island of Hawai’i, my home island, where traditional land divisions called ahupua`a joini at the sacred center of the island, Mauna Kea. Another name for this sacred mountain, Mauna Kea is Ka Piko O Ke Honua, which means “the navel of the Earth.” The theme of the navel also resurfaced in the Hawaiian language of the rituals to consecrate sacred space. Homes were seen as sacred structures. No one was allowed to enter until after a traditional priest, a kahuna blessed it. In the ritual blessing, the kahuna would declare that he was cutting the piko, or umbilical cord, of the house. This was very similar to the blessing of newborns. It seems that the house was seen as a living thing. Not only does the consecration of sacred space require ritual, once a place has been consecrated one must follow ritual behavior and language to enter that now sacred place. Through my research I discovered that behaviors deemed as proper ritual in order to enter sacred space in Hawai’i are: (1) asking for permission to enter (at times including the removal of shoes); and (2) giving thanks once that permission has been granted. In the study specific place names, I chose three kinds of sacred places: mountains, man-made temple structures (heiau), and bodies of water. I then picked one of each of those from the four largest Hawaiian Islands (Hawa’i, Oahu, Kaua’i, and Maui). Below I include only two.  Through the analysis of these sacred place names a few interesting key points emerged. In the naming of sacred places, the English words “royal” and “heavenly” are one word in Hawaiian, lani. Temples, heiau, are frequently named “House of [a god or chief].” In Hawaiian culture, temples are the house of god(s). Just as in the ancient Near East, in ancient Hawai’i mountains were seen as sacred temples, as evidenced by naming patterns. This research developed into an honors thesis, which is bound in the Honors office. I will also be presenting this research at the American Names Society’s annual conference in San Francisco in January, held in conjunction with the Linguistic Society of America. Dr. Hallen and I will co-author an article based on this that may be published in the linguistic journal, NAMES.

Through the analysis of these sacred place names a few interesting key points emerged. In the naming of sacred places, the English words “royal” and “heavenly” are one word in Hawaiian, lani. Temples, heiau, are frequently named “House of [a god or chief].” In Hawaiian culture, temples are the house of god(s). Just as in the ancient Near East, in ancient Hawai’i mountains were seen as sacred temples, as evidenced by naming patterns. This research developed into an honors thesis, which is bound in the Honors office. I will also be presenting this research at the American Names Society’s annual conference in San Francisco in January, held in conjunction with the Linguistic Society of America. Dr. Hallen and I will co-author an article based on this that may be published in the linguistic journal, NAMES.