Adrien Mooney and Dr. Glenna Nielsen-Grimm, Anthropology

Background

The Pueblo people of the Southwestern United States have a unique set of beliefs centered on the practice of ceremonies dedicated to kachinas, intermediaries between the Pueblo people and their deities. The word kachina literally means “life-bringer,” and the kachina ceremonies are integral for the growth of crops in the Pueblo region, as the kachinas bring rain to the region when ceremonies are performed correctly. There are three different manifestations of the kachina: the spirit of the kachina, the kachina mask worn by a dancer in the ceremony that allows the dancer to act on behalf of the kachina, and the kachina doll given to Pueblo children in order to teach them about the ceremonies and purposes of each kachina. These religious beliefs are collectively known as the “kachina cult,” and the practice of this religion throughout many of the Pueblos in the region has kept the Pueblos more or less peaceful for around 500 years. Scholars have researched where the kachina cult originated, and have pointed toward Mesoamerica as the source of much of the ritual material that has been incorporated into the kachina cult. However, much of this research has not been synthesized to state what the origin of the kachina cult likely was and how it developed once it was present in the Pueblo region.

Research and Methodology

I approached the project by pulling together and studying the current scholarly research on the topic, including research done by some of the most prominent modern Southwest archaeologists. After the initial research was completed, I synthesized the information in order to state what scholars believe is the origin of the Pueblo kachina cult. I first reviewed the studies which proposed theories that the kachina cult was brought by the Spanish in the early 16th century (later disproved by material evidence) or that it was created indigenously within the Pueblo region long before the Spanish ever arrived and likely before trade was ever taking place with developed societies in Mexico. Most modern scholars, however, seem to agree that the kachina cult, or at least elements of it, were communicated to the Southwest from Mesoamerica. The leading researchers in this area do disagree on how and where the kachina cult developed once the elements of it were present in the Southwest. Polly Schaafsma, a scholar who studies ancient rock art in order to determine the origin and process of cultural developments in the Southwest, believe that the Pueblo kachina cult derived from ritual beliefs of Mesoamericans in the southern Mexico culture region. These elements of ritual belief were traded to the Southwest along with material items and then adapted to meet the needs of Pueblo residents. Schaafsma believes that, through the evidence provided by pictographs and petroglyphs drawn on rocks, it can be proved that the kachina cult began more prominently in the eastern pueblos, later spreading to the west. E. Charles Adams, an archaeologist who also studies the origins of the kachina cult but uses pottery, wall murals painted inside kivas (underground ceremonial centers), and architecture as evidence, believes that the kachina cult developed in the western pueblos and spread eastward. However, both of these archaeologists do agree that the kachina cult developed from elements of Mesoamerican ritual beliefs and was brought through the great trade center of Casas Grandes to the Pueblo area, one of the most important but understudied civilizations in the greater Southwest region.

Casas Grandes, whose ruins are located in the modern-day Mexican province of Chihuahua, is believed to be one of the main reasons trade was so prevalent throughout the Southwestern region and Mesoamerica. Casas Grandes and its capital city of Paquime were integral to the trade connections formed throughout the Southwest. Its central location and beautiful and desirable pottery made Casas Grandes a prime trade center for Mesoamerica, the Southwest, and areas to the west, north, and east of the region. As any study of trade throughout regions has shown, non-tangible ideas are traded just as readily just as material objects are traded between groups of people.

Results

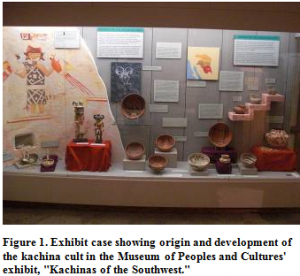

After completing the research for this project, I synthesized all of the information in collaboration with my mentor, Dr. Glenna Nielsen-Grimm. She helped me to keep the project focused and make sure that the paper I wrote would best fit in with the Museum of Peoples and Cultures’ newest Popular Series publication, entitled “Mesoamerican Influences in the Southwest: Kachinas, Macaws, and Feathered Serpents.” After I completed the paper, it was included in the MPC’s aforementioned Popular Series #4. This collection of papers is currently available at the Museum of Peoples and Cultures and corresponds with the current exhibit, entitled “Kachinas of the Southwest: Dances, Dolls, and Rain.” The research I did for this exhibit tied the kachina exhibit together with the other exhibit currently on display at the MPC, entitled “Touching the Past: Traditions of Casas Grandes,” which examines the pottery traditions as well as the rituals and trade centrality of the Casas Grandes region.

The information that I gathered and synthesized during the research portion of my project was translated into one of the exhibit cases in the MPC’s Kachinas of the Southwest exhibit (Figure 1) which focused partially on the archaeological evidence for the origin of elements of the kachina cult from Mesoamerica and partially on the development of the kachina cult within the Pueblo Southwest, again using archaeological evidence (such as pottery, rock art, kachina dolls, a copy of a kiva wall mural, and other various artifacts) to show the ways it developed among the Pueblos.