Eric C. Darsow and Drs. Christopher Meek and Warner Woodworth

Nonprofit organizations (NPOs) face a tradeoff between activities which further their mission and those which generate revenue to pay salaries and bills. For many NPOs, management’s increasing attention to cash flow suppresses the organization’s service-oriented mission and alienates staff. This ORCA grant funded a case study of this phenomenon at RSEF, a small development NPO in South Africa. I use organizational identity theory to explore ways in which a loss of mission focus affects how staff identify with their work, and how decreased identification impacts the organization’s ability to serve society. By understanding the relationship between job commitment, organizational identification, and program effectiveness, managers can fashion NPOs that fully engage staff with their work which, in turn, leads to more successful social service programs.

I conducted my investigation of organizational identity at RSEF as a volunteer intern during two, three-month long visits to South Africa. My time included both active participation in the day-today organizational tasks assigned by my supervisors and research-specific conversations, interviews, and outings. I conducted 32 semi-unstructured interviews with current RSEF staff from all levels of the organization, former RSEF staff, and independent contractors.

Mission Drift and Organizational Identification

RSEF, like many other NPOs in South Africa, attract staff members who feel a strong need to contribute meaningfully to their community. As such, many work at RSEF for more than a salary; their individual identity as a contributing member of South African society is integrally related to the work they do at RSEF on a day-to-day basis. One such example is Kathleen, who started work at RSEF over a decade ago. She describes what motivates her to continue the exhausting work of conducting teacher assessments in the deeply rural areas of the Eastern Cape:

You will drive in different weather: hot or cold or windy or rainy because you’ve got this umph—this passion—in you that you want to get to these people. You want to give to these people what you know and what they do not know so they are able to take this to other people… and empower them.

Later during the same interview, however, Kathleen’s tone and outlook on education development abruptly shifted. Reflecting on the work environment at RSEF, she revealed a second, drearier set of emotions about her work at RSEF:

People don’t trust one another here… Some people are heard and some people are not heard… These are the things really, at the end of the day, I will say to myself ‘why should I worry. Just do what they tell you to do.’ …I am working because I want to put food on the table. Each day I don’t want to go without a meal at night, when I’m [home] from work.

What could cause an employee like Kathleen, whose commitment to community development runs so deep, to feel so disconnected from both her organization and the work she expressed such passion for just minutes earlier? The demands of keeping money flowing through RSEF to pay 1 Dutton, Jane E., and Janet M. Dukerich. (1994). Organizational Images and Member Identification. Administrative Science Quarterly, 39, no. 2, p. 242 2 bills and salaries is a key contributor. Despite attempts to eliminate the mission-money tradeoff by generating income through program fees, RSEF remains reliant on government serviceprovision contracts for its financial viability. RSEF has coped with the strain of administering many unrelated contracts by centralizing decision making authority among upper management and increasing its dependence on external contractors.

I argue that these coping strategies, not RSEF’s reliance on the government, erode the staff’s organizational commitment because each member’s own identity—their sense of purpose and meaning—is no longer reflected in RSEF’s new, money-driven identity. As their identification with RSEF weakens, staff who once worked long hours for low pay now find themselves working just for paychecks. Using terminology from identity theory, “the strength of a member’s organizational identification reflects the degree to which the content of the member’s selfconcept is tied to his or her organizational membership.”1 Disengaged staff and their wait-untiltold mentality results in a less vibrant social service agency; both the staff and community members suffer.

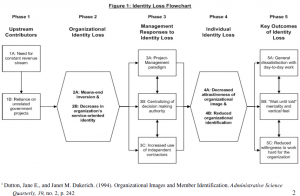

Figure 1 graphically depicts the relationship between organizational characteristics and individual work identification. Phase 1 on the far left of the diagram contains the funding-related upstream contributors to RSEF’s organizational identity loss, represented by Phase 2. In this second phase, the organization’s need to keep money flowing into the organization (the means) overrides its intended end—community development, creating a means-end inversion. Phase 3 depicts management’s responses to RSEF’s financial constraints and the mean-end inversion they produced. Next, Phase 4 shows individual identity loss because of the way in which management’s actions impacts individual staff members. Finally, the decreased organizational identification leads to the concrete organizational outcomes listed in Phase 5.