Eric W. Linton

Introduction

In the summer of 2009 indigenous groups in the Peruvian Amazon headed a major grassroots movement against the national government in an effort to protect their lands and lifestyles. The protests brought due international attention to issues of human rights and land ownership that had previously been a local matter. Several months previous to the movement a colleague and I ventured to the Putumayo region of the Peruvian Amazon in an effort to understand the issues being faced by the people of those regions. Specifically, we aimed to understand the importance of self determined rights as a means to preserve tradition and culture. In addition, we wanted to understand what the threats to indigenous rights are and what they are doing to overcome those threats through political means.

The last decade has proven to be a very profitable one for Peru. The GDP has doubled as a result of new policies concerning land and water rights. The Amazon of Peru has played a significant part in the economic success. However, the success has not come without a cost. Increasing developments in the Amazon have brought indigenous rights to the forefront of the Peruvian political dialogue. Specifically, the increased development correlates positively with human rights infringement and the policies used to implement the development are questionable.

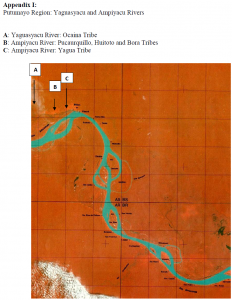

The primary purpose of this article is to understand how the Yagua, Ocaina, Bora, and Huitoto tribes along the Ampiyacu and Yaguasyacu rivers in the Putumayo region of the Amazon have been influenced by modern development such as mining, logging, and other external influences, and what they are doing to preserve their traditional lifestyles. As we document the tribal lifestyle we will focus on how the tribes preserve their culture and what role the tribal, regional, and national government play in the success of those endeavors. Two aspects of cultural preservation are investigated. First, how each tribe is organized politically and second, what role the environment and land plays in the cultural preservation of the tribes. The specific focuses of tribal culture will include traditional everyday knowledge of their habitat such as plants and animals, oral traditions, native languages and the use of land.

Traditional languages, customs, and overall cultures are often altered as a result of development. The tribes of the Putumayo region of the Amazon have undergone definite cultural changes as contact with outside influences has increased. There are certain aspects of the tribal cultures that have been preserved and certain methods used to preserve them. Among the methods used to preserve tribal cultures, the emphasis on land ownership, teaching traditional languages, the preservation of a traditional tribal government organization, and the maintaining of oral traditions are imperative.

Some indigenous groups in the Peruvian Amazon are using violent protests because contextual examples have proven that without proper democratic representation, another effective way to influence to the government and protect land rights is through demonstrations. Many indigenous people feel that the government is a separate and confronting body and they do not feel as if they are a part of the dialogue that is taking place between the government and prospective industries. They recognize that a dialogue that concerns their lands and livelihoods has taken place between government leaders and industrialists yet they have remained excluded.

The final outcome of this research will provide a perspective of the tribe’s existence in context of history and modernity. We will look at the vital parts of tribal society and what, if anything is being done to preserve that society. The research will provide insightful information on how the tribal government functions within a state government.

History of Development in Putumayo

The influence of modern development has played a significant role in the history of indigenous groups in Peru, including the tribes in the Putumayo region. From the first interactions with outsiders during the rubber boom, the tribes in Putumayo have associated development with violence and suffering. For the tribes now located along the Ampiyacu and Yaguasyacu rivers in Putumayo, this introduction to modern society and development occurred fairly recently in comparison to other tribes in Peru.

In more accessible regions of Peru like the Andes and the Selva Central, indigenous groups confronted colonizers and developers beginning in the 16th century. Because of the remoteness of the Putumayo region many initial contacts with these groups were made by couchos or rubber tappers around the turn of the century, by soldiers during the Colombia Peru Leticia war from September 1 to 1932 – May 24, 1933 and also during a second insurgency of rubber tappers during the Second World War. The first contact with the couchos was devastating for the tribes of the Putumayo. Tribesmen were exported like slaves throughout the region to tap the rubber trees. Older members of the Yagua, Ocaina, Bora, and Huitoto tribes still recall the punishments imposed on those who would not bring back enough rubber. Castration, foot and arm amputations were among some of the punishments. The less fortunate were killed by machete, burned, or drowned. Walter Hardenburg was a witness to the brutalities during the rubber boom and documented that Indians were exterminated or tortured for bringing insufficient amounts of rubber or at other times for mere pleasure (Taussig 1984, 467-497). Besides the brutality of the couchos, small pox and other plagues took their toll and entire villages were left desolate.

During this time the population of the Bora tribe in the Putumayo went from nearly 15,000 individuals to a mere 450 (Dan James Pantone, Amazon Indians). Four thousand tons of rubber was exported from the Putumayo in the first decade of the 20th century and the overall indigenous population in the region decreased by nearly 30,000. The introduction of the rubber industries did no only bring physical destruction. It challenged the existence of traditional tribal culture by introducing competition and monetary usage which was previously foreign the communities. In 1912 The Contemporary Review described the Indians of the Putumayo as more morally developed than their oppressors and lacking a sense of competition. The Indians were “socialist by temperament [and] habit (Taussig 1984, 474).”

Since the rubber boom, many of the tribes that did not assimilate to modern societies eventually relocated to their present location along the Ampiyacu and Yaguasyacu Rivers. The Yagua, Ocaina, Bora and Huitoto were among the tribes that moved south of the Putumayo River and established new communities and rebuilt their tribes. Despite what one might think, the devastating effects of the rubber boom did not completely destroy the traditional tribal culture among these tribes because they preserved the traditional connection with land, water and natural resources which they found in abundance in their new locations. The tribes have maintained certain aspects of the socialistic lifestyle where each member of the tribe works for the well being of the community.

Tribal Organization and Preservation

The tribes have undergone certain changes because of the events during the rubber boom and subsequent developments like logging and mining. Because of the consistent threats of squatters, industries and certain policies, the tribes have adapted by becoming more politically organized. The new political organization is an important part of the preservation of the culture and autonomy of the tribal government.

The tribes in the Peruvian Amazon, as in other places, are usually divided into smaller communities that may be very isolated from one another. This is the case with the Yagua, Ocaina, Bora, and Huitoto communities along the Ampiyacu and Yaguasyacu rivers. Each community belongs to its respective tribe. In each of the four tribes there are tribal community leaders and authorities that consist of the president who is chosen democratically by the tribe to represent the tribe in external political matters, a chief or curaca who is chosen to guide the tribe in spiritual and traditional matters, and teachers who are educated and responsible for the education of the tribes children and youth.

The president of the tribal community holds frequent meetings in the community to discuss matters from community law to external development issues. The presidents of the four tribes hold quarterly conferences in which they discuss matters that are relevant to their communities. The president represents the community before a non-government organization called the Federation of Native Communities of the Ampiyacu (FECONA).

The curaca is chosen in each community by its members. The curaca is responsible for teaching spiritual matters, traditional language, and other traditions like song, dance, and medicine. Although the curaca can be involved in external affairs of the tribe along with the president, his primary concerns are domestic issues. The curaca is a traditional position equal to a shaman and much of the cultural traditions that are taught by the curaca are intertwined with the natural resources provided by the land around them.

The teachers in the community are usually members of the tribes that are employed by the state to provide a formal elementary level education to the children of the tribe. The four communities of the Ampiyacu and Yaguasyacu have been provided by the state with a one or two room school house where the teachers teach basic reading, writing, and arithmetic. Teachers also share the responsibility to teach the native tribal language.

The president, curaca, and teacher play important roles in preserving the tribal culture. Although the president and teachers are not traditional positions within the tribe, their influences help to perpetuate the tribal culture by giving it a degree of political legitimacy. Presidents and teachers are ways in which the tribes have developed in order to become involved in local and national politics.

Although some tribes, including the Yagua, Ocaina, Bora, and Huitoto of the Putumayo region, have adopted basic forms of agriculture and farming, the majority of food still comes from the rivers and forest around them. Their basic agriculture has allowed them to maintain non-nomadic lifestyles. The water that is used for drinking, washing, and cooking is almost exclusively obtained from the rivers that flow around them. Many of these natural resources, including natural food and water supplies would be negatively affected by the establishment of mines near the communities. Natural resources that the tribes depend upon like the wildlife, plants, and the land itself are all variables that are affected by development. The prospects of developments, and the tribes’ dependency on the natural resources that are affected by development, have forced the tribes in the Putumayo to become more politically involved than ever before.

Contemporary Crisis

In 2007 and 2008, President Alan Garcia passed legislation that would have a significant impact on indigenous groups throughout Peru and especially in the Amazonia regions. The laws were made in conformity to the United States- Peru Trade Promotion Agreement (TPA) which eliminated restrictions on about 45 million hectares of the Amazonian lands for development. This was done without any consultation with the communities that occupied the lands. Law 29157, published December 20, 2007 by the Congress of Peru, gave delegated power to the executive branch with subjects related to the Peru-U.S. Trade Promotion Agreement (Foreign Policy in Focus).

With delegated authority concerning TPA issues, President Alan Garcia made a number of controversial decrees that opened up opportunities for private investments, including privatizing land and water rights. Much of the newly accessible lands are used by and inhabited by indigenous groups whom were not consulted with in the formulation of the decrees. In December 2008 a multi-partisan commission initiated and investigation into the dispute between the indigenous groups and Garcia’s administration. The final report that was published called the decrees made by Garcia illegal and unconstitutional. Regardless of the report the decrees were put into effect (World Politics Review).

“We know [the government and industrialists] are talking,” says a teacher in one of the Bora communities, “but we don’t have a part in the dialogue… They have us like animals… They could come and kick us out of our lands… and what would we do (Interview with a teacher in the Bora tribe 2009)?”

The teacher’s concern is legitimate especially since the Bora community in Pucaurquillo, like most tribal communities, has no official title to the lands they currently live on. Decrees 994 and 020-2008-AG provided a facilitated track for private developers to obtain a title for “idle and unproductive lands”. The land described as idle and unproductive is most often inhabited by indigenous groups that rely on the land for the perpetuation of their cultures and livelihoods. At the very least a title is required by law for legal protection against a state sponsored initiative, but the process for obtaining a title is not an easy one. In 2002 the Ombudsman’s Office identified at least 17 steps in the process of obtaining an indigenous land title. In Indigenous Rights and Development: Self-Determination in an Amazon Community, Andrew Gray reported as many as 26 steps in the indigenous title process and a timeline as long as 15 years (Council of the Americas).

President Garcia made the decrees with the purpose of increasing the level of economic competitiveness in the region. The tribes in the region understand the ways that their lifestyles would change should industries be permitted to develop their land and resources. More than the immanent threats of development, the main concern of the tribes is their legitimacy in deciding their own fate.

Peru has much to gain from the agreement as it promotes stronger economic relations between the United States and Peru. The agreement presents substantial opportunities for foreign investment in agriculture, lumber, mining and livestock, thus generating more employment and increased competition in the region. For the four tribes of focus the most impending concern is the development of logging and mining industries. Currently the largest oil producer in Peru is Pluspetrol, an Argentine- based company which turns out about 69% of Peru’s crude oil production. In 2007 Peru was consuming 145.29 thousand barrels of oil a day but it only produced 113.8 barrels a day. Since 1993 Peru has been a net importer of oil and so there is increased pressure on the further development of the petroleum industry (MBendi Information Services).

Petroperu is a state-owned company and it is the most concerning company for the four tribes of focus. The industrial refinery is located in Iquitos and is capable of producing 10,500 barrels of crude oil per day. The oil that is extracted from the region is exported throughout northeastern Peru including some locations in Ecuador and Brazil. Petroperu is an important contributor to the nation’s overall oil supply, but their website states that in recent years “the quality of petroleum extracted in the northern jungle has decreased”. Petroperu is the most prominent oil company in the region that pertains to the four tribes of the Ampiyacu and Yaguasyacu Rivers. Oil exploration is an increasingly important pursuit for Petroperu and all those that are dependent on the oil from the region. Logically, with the quality of oil extracted and the current wells getting poorer, Petroperu has an incentive to expand their oil extraction into new regions like the Ampiyacu or Yaguasyacu areas.

The tribes recognize the benefits that are presented by the trade agreement; however, they are suspicious that whatever profit is made by the agreement will have little positive impact on the indigenous population. Ambitious prospectors have already undermined the legitimacy of tribal governments and their self determined land rights in the Putumayo. The Curaca of the Huitoto community said, “Yes [mining] could change [our culture] because these resources in these lands are ours. And we can’t let people come in that are cheating us… for example the oil drillers or the dredgers. The dredgers came in from the Amazon and up the [Yaguasyacu] tributary without us knowing (Interview with the curaca of a Huitoto community, 2008).” According to the curaca, his major concern involves more than the environmental changes that mining would present to his community. Above all, the curaca is concerned that they might be cheated out of their land and their self determined rights be undermined. Mining is not the only industry that has secretively intruded the tribal territories. Loggers have also been a consistent problem. Nearly all of the large lumber trees along the Ampiyacu and Yaguasyacu rivers where the Yagua, Ocaina, Bora, and Huitoto, communities live have been harvested. The logging that has taken place is sufficient to distinguish clear alterations in the forest canopy along the rivers from satellite images.

Decree 1090, the New Forestry Law, declares that deforested areas be removed from the patrimony of the state and therefore opening up the land for private sale and agricultural use. For the Huitoto and the Bora tribes that share the village of Pucaurquillo, illegal logging is more than losing trees, it is the first step in opening the land for private retail and losing the land they live on (El Congreso de la Republica del Perú, 2008).

President Garcia intends to create a spirit of competition under the authority of the TPA to overcome the “ideologies of laziness” that exist in areas like the Amazon. President Alan Garcia addressed the opportunities in natural resources and the obstacles preventing their development.

“There are millions of hectares of timber lying idle, another millions of hectares that communities and associations have not and will not cultivate, hundreds of mineral deposits that are not dug up, and millions of hectares of ocean not used for aquaculture. The rivers that run down both sides of the mountains represent a fortune that reaches the sea without producing electricity. Thus, there are many resources that are idling untradeable, which do not collect investments or generate employment. And all for the taboo of ideologies overcome by laziness, by sloth, or the law of the dog in the manger which reads: “If I don’t do it myself, may nobody do it at all” (Garcia 2007, Perro Hortelado).”

The ideology that I witnessed in the tribes was not “If I don’t do it myself, may nobody do it at all.” Instead, the tribes that I observed implied, “If we are not consulted with, we are not consenting.”

Decree 1090, commonly called the “Law of the Jungle” by the indigenous people, overruled the protected status of 45 million hectares of the Peruvian Amazon. Decree 1064 facilitated changes in zoning permits for prospective investors. With delegated authority, Garcia made more than 100 decrees concerning the U.S.- Peru TPA, including a law in February 2009 that legalizes squatters on more than 250,000 locations on private lands that were settled before 2005 (The Economist). In response to these free trade decrees, tribes across the Amazon rallied and protested against the exploitation of their lands and water (El Congreso de la Republica del Perú, 2008).

In March 2009 The Economist called Garcia’s decrees a “recipe for conflict”. The statement proved prophetic on June 5 when peaceful protests reached a pinnacle point in the Bagua province and police open fired on a group of indigenous protestors that had blocked regional roads, rivers, and shut down a major oil plant. Reports from the communities accused the police of dumping some of the bodies of the dead in a nearby river. The tribes reacted and killed dozens of the police officers and held others hostage. In the end, the confrontations between the indigenous protestors and police officers resulted in more than 50 deaths altogether.

The violent conflict brought international attention to the events taking place in the region as well as to Garcia’s decrees. Many organizations including El Comercio accused the government of failing to uphold human and indigenous rights as set forth by the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. On the 8th of June 2009, decree 1090 and 1064 were suspended.

The Representation Problem

The success of the indigenous protests and the complexity of their grassroots movements are indicators that the political representation for the tribes on a national level is weak. Through protests the tribes have found a way to interpose themselves in the dialogue that is so crucial for their lands and communities. The communities along Ampiyacu and Yaguasyacu Rivers, like most indigenous communities, have not taken part in the public protests. They are, however, supportive and aware of them. Living along small tributaries of the Amazon and hundreds of miles from any type of paved highway these communities are not in the forefront of the conflict between indigenous peoples and the government. But they watch from afar and they are as concerned about their self determined rights as any other communities. When asked a young woman in the Bora community about how represented she feels, she said that currently, the national government is making arrangements to let other countries come in and take oil from what she feels are “their” lands (land that they have no title to but that they use and depend on for livelihood) (Interview with young woman in the Bora tribe, 2008).

Like all the indigenous communities in Peru, the tribes in the Putumayo region of the Amazon face significant problems due to the nature of their representation. The principal problem is the basic democratic process that overlooks minority groups like those that are isolated in the jungle. These tribes have no part in voting for any public officials and as a result the public officials have no accountability for those people. This means that the tribes do enjoy the privileges of creating their own systems of government with the rights to create their own communal laws and processes, but it also means that beyond their communities they have little ability to take part in the national democratic process. Their need for representation has been acknowledged by private organizations like The Federation of Native Communities of the Ampiyacu (FECONA). The tribes of the Putumayo are able to vote every three years to elect a representative that will represent them before the government.

FECONA represents the needs of 13 tribes in the Putumayo, including the four along the Ampiyacu and Yaguasyacu Rivers. FECONA is only one of more than 55 similar organizations that represent distinct regions and report to the National Organization of the Amazon Indigenous people of Peru (AIDESEP). These organizations are not a legitimate governmental entity, so in the end the indigenous communities are left to find some form of representation even if it means doing it through the private sector.

The tribes in Putumayo along with almost 1,350 other communities depend on AIDESEP to represent their needs to the national government. AIDESEP played an important role in organizing the Bagua protests and lobbying their rights before the national congress. Similarly, when the Huitoto tribe had issues with invading miners and loggers in 2007, AIDESEP was there to represent them in Lima and the machines and developers that had invaded their land were removed. But since then, the Huitoto’s say they have not seen a representative from FECONA or AIDESEP even though there are supposed to be monthly visits.

“Now it’s as if we were abandoned like orphans without a father… without a guide to help us work (Interview with the curaca of the Huitoto tribe 2008).”

Organizations like FECONA and AIDESEP are strong lobbyists for the rights of indigenous people when there is crisis, but it does not replace the need for consistent and official political representation before the national government. The fact that the tribes depend on monthly visits from these organizations implies a top down bureaucracy rather than a bottom up democracy. In addition, organizations like FECONA and AIDESEP have little accountability to their constituents since the tribes remain for the most part isolated by the forest and with limited means of communication.

When we asked two women in the Yagua tribe what they would do if they had a problem or a complaint for the regional government, they had no idea. Eventually they determined that their chief could probably go to Iquitos to be heard, but they said that there is little money at their disposal to be able to make such a trip. Going to Iquitos is not an easy task. For passage to Iquitos the entire community compiles funds to send one representative. Once the representative arrives in Iquitos things aren’t any easier. The biggest problem is finding someone who will listen.

Within each of the four observed tribes a representative or president is elected by public votes. This representative may make occasional trips to Iquitos where FECONA has its office. The trips to the city most often prove unfruitful. Rumors circulated in the Bora community about the tribe’s representatives receiving bribes in cash and alcohol from authorities within FECONA. Whether the rumors are true or not, in the end, the tribes feel like their voices seldom make the way up the bureaucratic ladder to the ears of those who make the laws.

The tribes recognize their dependence on the land and rivers around them and they are aware of the speculative industries that would affect them. They are aware that mining industries would have a significant effect on their traditional culture and they want to be recognized as legitimate governments that have the self determined rights to dictate their future whether they decide to permit modern developments or not.

During these times of political unrest and economic prospects, these four tribal communities are not homogenous in their views of industrial development. They face the challenge of creating a cohesive identity that can span the distance between villages, tribes, and languages and give the people a solid voice at the table of national politics and policy making. For this reason, many indigenous protests, like those in Bagua, have been isolated and inconsistent. The views of individuals and collective tribes range from isolationism to assimilation; however, one thing that the tribes do appear to agree on is that the decrees made by Alan Garcia undermine their self determined rights to dictate what happens to their communities and the future of their tribes. Long periods without contact and rumors of bribes have created a sense of distrust towards the very organizations that represent the Putumayo and the Ampiyacu communities—FECONA and AIDESEP. Whether these rumors are true or false remains a question, but the fact that the rumors exists and are perpetuated throughout the tribes implies that there exists a problem of representation.

Culture and Tradition

The Yagua, Bora, Huitoto, and Ocaina communities have clung to their cultures by creating a tribal government that combines traditional hierarchal positions like the Curaca with more modern positions like the tribe president and school teachers. Like any society, these public positions are established for the purpose of protecting certain liberties that the community values. Within these communities the traditions that are most valued are closely tied with the environment around them. The style of their homes, dress, song, dance, stories, medicines, and even languages are contingent upon the environment. Much of the efforts of the officials in the tribe are spent protecting these commonly held values. The trips to Iquitos, the meetings with other tribal leaders, and the interactions with organizations like FECONA or AIDESEP are done with the mission of protecting the tribe’s self determined rights.

One way in which the tribes maintain traditions is in the uses for plants around them. The Ocaina tribe, for example, has infused the use of the Coca leaf with the cultural identity of their tribe. Like the other three tribes, the Ocaina have what they call a maloca or a communal meeting house. Inside the maloca, the Ocaina sustain a type of factory. The coca leaves are dried by the fire and then placed in a hollow trunk and beat with a wooden rod. The leaves of the setico plant are burned and the ashes are mixed with the crushed coca leaf. Unlike the other fine powder produced by the coca leaf (cocaine), the coca powder is not a hallucinogen but a stimulant. The powder is packed in the cheek and it allows one to work without becoming too tired or hungry. However, the coca leaf is more than a stimulant for the Ocaina, it is a tradition that has created a coherent identity for the Ocaina from one generation to the next. They are proud of their traditions because it distinguishes them from other indigenous tribes.

There also exist traditions, knowledge, and history that are held by a more broad demographic of indigenous peoples. Vicente of the Yagua community lives with his family on a small peninsula with the Ampiyacu River on one side and a lagoon that is left from the Ampiyacu’s ancient rout on the other. Past the lagoon is a stretch of land that continues until the banks of the Amazon River. He took us on a hike through those woods and educated us on some of the plants and their uses. A small path took us to a tree that looked like it had been well used. The bark was cut all around the base and Vicente explained that the sap that drips from the tree is used as a blood coagulant and it is useful for healing women after childbirth. The tamuri tree is also important to the Yagua and it is used to calm the fever. The cumaseba tree is used as a general pain killer. The bark of the chanchama tree has been used for generations to make clothing for the Yagua and many other tribes. Continuing further, we came across another tree that appeared to have been cut so much that it was practically destroyed. He called it the caucho tree and explained that the thick sap of the tree could be boiled to create a tough material—rubber. It was this tree that began the rubber boom in the Amazon and lead to the exploitation of the indigenous tribes to work as slaves for its production. Vicente explained that his ancestors were tortured and killed when they were unable to bring back enough of the sap to satisfy the demands of the couchos (Interview with Vicente Alvan 2008).

Vicente’s knowledge of the plants of the forest and his understanding of the history of the rubber boom were passed to him orally from his parents and he passes the knowledge to his own children in like manner. Conversations about the mysteries of the jungle are common in the evenings when people are talking around the firelight. They have passed a traditional suspicion of whites and outsiders since their initial contact with them from the rubber boom. Since much of the history of the rubber boom is recorded simply through oral stories, Hardenburg points out that whether exaggerated or not, “the narratives are in themselves evidence of the process whereby a culture of terror was created and sustained (Taussig 1984, 482).”

The most recent generations have overcome extreme fear of whites and outside people, but members of the Yagua tribe along the Ampiyacu River recall being taught as children that white people were to be feared. These traditions are being overcome and the tribes are once again opening up to visitors, even encouraging tourism to their communities. However, one can still sense the paranoia of outside influences and the tribe’s determination to remain separate from those pressures. When an outsider visits the tribe he or she is expected to bring some kind of an offering to present to the tribe. If the individual is permitted to visit the community the tribe will offer a drink of masato. The drink is made from the root of the yuca and when mixed with water it becomes milky and it easily ferments. Some of the four tribes are more welcoming of visitors than others, but all of them share a sense of protectionism over their people and customs.

The tribes of the Ampiyacu and Yaguasyacu Rivers are for the most part self-sufficient and desire to maintain a degree of isolation. However, there are ever-increasing variables that encourage the tribes to rely less on isolationism and more on assimilation. Although the Yagua tribe on the Ampiyacu River is located near the town of Pebas, they rely more on hunting and fishing than transactions in the market in Pebas. Their primary source of protein is from the fish they catch from the Ampiyacu. The fish they depend on most include Piranha and a variety of cat fish. Primarily the men in the community assume the responsibilities for fishing and hunting and the women do most of the cooking. The consensus among the men in the community is that the size and quantity of the fish in the river have decreased substantially even in the last decade. The average size of fish caught over the two-day period we observed was approximately 6-8 inches. The tribesmen claimed that the fish were previously much larger and there used to be a greater variety of fish. Large fish like the tungaro have become increasingly scarce. The sustainability of the natural reproduction of fish, plants, and animals is a determinant for the sustainability of tribal autonomy. As the natural resources of the jungle become increasingly scarce, the pressure for tribal assimilation to more modern societies increases concurrently.

The Yagua, Bora, Huitoto, and Ocaina are only a few of the tribes that have decided to maintain traditional lifestyles and resist assimilation into more modern societies. With a growing market for resources like oil and gas that are abundant in the Amazon, the tribes of the Putumayo region face an additional threat to their self determined existence. Garcia’s initiative to develop the Amazon and the prospective gas and oil miners exploring deeper into the forest threaten some of the vital aspects of the tribal cultures— land, animal, and water resources. Tribes have responded to the changing environment and the impending developments by becoming increasingly involved politically and private organizations like AIDESEP and FECONA have aided them in their political involvement. However, the tribal political institutions lack direct involvement through democratic representation that is necessary for political legitimacy.

We sat with the presidents, curacas, and teachers of the Bora and Huitoto tribes in their maloca in Pucaurquillo. The dialogue between the two tribes was not one of antidevelopment or antigovernment. The teacher of the Boras talked about the importance of the education of their youth in the fields engineering and agriculture so they could come back and educate the elders in the community as well. An elder Huitoto talked about the importance of land and the need for sufficient land for their children and future generations. They talked about the future of their tribes and the circumstances that their children would inherit. They expressed their frustration in the difficult process that is required for obtaining a title for the land they currently live on. They understand that the repercussions for living on untitled and “unproductive” land could be devastating if the government or mining industries find their land to be rich in petroleum resources. They feel threatened. Their close neighbors, the Ocaina, actually have a legitimate title for their land; nevertheless, just two months before our visit they found out that petroleum exploration was taking place on their land. “It was a big hit to our community” said the president of the Ocaina village.

The tribes’ concern for sufficient land for future generations is a legitimate one. For example, if we were to consider the Bora community of the Yaguasyacu River an autonomous nation and compare the people per square kilometer in the Bora nation to the people per square kilometer of the Peruvian nation, the Boras would have about 33 percent more people per square kilometer than the Peruvian square kilometer. In reality, the Boras are not an autonomous nation and they live under the jurisdiction of the Republic of Peru. Article 88 of the Peruvian constitution guarantees the right of ownership “sobre” (over) the land. This means that the state owns all of the resources that are found beneath the surface of the land such as minerals, water, and petroleum. Ultimately, even with a land title, the indigenous communities feel threatened by the state.

Conclusion

The Yagua, Ocaina, Bora, and Huitoto tribes in the Putumayo have been influenced by modern development since their initial contact during the rubber boom. One of the effects of modern developments on the tribes has resulted in a more organized tribal society with presidents, teachers, and curacas that give the tribes more legitimacy in regional politics and preservation from within.

Although major improvements in tribal representation were made with the creation of organizations like FECONA and AIDESEP in the 1980s, occasional representation is not sufficient for the needs of the communities under their jurisdiction. With the current system of representation FECONA and AIDESEP have little accountability for the tribes during times where there is no major crisis. What the tribes want is to be recognized as a political self-determining entity. Until there is a more direct form of representation it would not be unlikely for conflicts like those in the Bagua province to arise when the tribes feel threatened. This occasional representation from private organizations encourages distrust among the already suspicious tribes.

With the new powers granted to the executive branch concerning the new Trade Promotion Agreement between the U.S. and Peru, non-government organizations like FECONA and AIDESEP are insufficient for proper representation for indigenous people in the Amazon. Decrees 1090 and 1064 were not sufficiently challenged until indigenous protests became violent and the attention of international organizations was drawn to the issue.

The successful suspension of some of Garcia’s decrees does not mean that the tribes are being properly represented; rather successful reform through violence only encourages more violence. The tribes in the Amazon continue to protest because the underlying problem still remains—the problem of proper representation. Until a more efficient and legitimate form of representation exists than international and national non-government organizations, tribes will continue to feel victimized by the government and its policies. The violent protests that took place in the province of Bagua embody the sentiment of tribes across the Amazon in reaction to political segregation. The current system of representation is not conducive for the sustainability of tribal autonomy and livelihood. The development that is encouraged by the Garcia administration threatens the natural habitat that allows the tribes to remain autonomous. The balance between economic profit and tribal sustainability is a delicate one, in which the value of human rights, human life, and culture should be considered. The current lack of representation of the indigenous community encourages policy makers in Peru to focus more on economic progress than on human rights advancement. According to the teacher in the Bora community, it is not about antidevelopment, it is about having the power to determine ones future.

Bibliography

- Asociación Interétnica de Desarrollo de la Selva Peruana. ¿Cómo estamos organizados? AIDESEP. http://www.aidesep.org.pe/index.php?id=2 (accessed August 22, 2009).

- Carlsen, Laura. “Trade Agreement Kills Amazon Indians”. Washington, DC: Foreign Policy In Focus, June 18, 2009. http://www.fpif.org/fpiftxt/6200 (accessed August 21, 2009).

- Democratic Constitutional Congress of Perú. 1993. Constitución Política del Perú title 3, Chapter 6, article 88. http://www.tc.gob.pe/legconperu/constitucion.html (accessed December 2009-January 21, 2010).

- Empresa Editora El Comercio. “Temor en la Selva por Retorno de la Violencia”. El Comercio, August 21, 2009. http://www.elcomercio.com.pe/impresa/notas/temor-selva-retorno- violencia/20090821/330941 (accessed August 22, 2009).

- The Economist Newspaper Limited. “The Americas. Whose Jungle is it? A Scramble for Land Sets Investors Against Locals”. The Economist, March 19, 2009. http://www.economist.com/world/americas/displaystory.cfm?story_id=13331350 (accessed August 22, 2009).

- The Economist Newspaper Limited. “Oil and Land Rights in Peru. Blood in the Jungle: Alan Garcia’s High-handed Government Faces a Violent Protest”. The Economist, June 11, 2009.http://www.economist.com/displayStory.cfm?story_id=13824454 (accessed August 22, 2009).

- El Congreso de la Republica del Perú. Comisión Multipartida. Comisión Multipartida Encargada de Estudiar y Recomendar La Solución a la Problemática de los Pueblos Indígenas: Periodo Legislativo 2008-2009. Informe Sobre Los Decretos Legislativos Vinculados a los Pueblos Indígenas Promulgados por el Poder Ejecutivo en Merito a la Ley 29157. December 2008. http://www.rightsandresources.org/documents/files/doc_956.pdf (accessed December 2010-January 20, 2010).

- El Congreso de la Republica del Perú. Executive. The President of the Republic. Legislative Decree 1090. 2008. http://www.congreso.gob.pe/ntley/Imagenes/DecretosLegislativos/01064.pdf

http://www.congreso.gob.pe/ntley/Imagenes/DecretosLegislativos/01089.pdf

http://www.congreso.gob.pe/ntley/Imagenes/DecretosLegislativos/01090.pdf (accessed December 2009-January 20, 2010). - García Pérez, Alan. “El Síndrome del Perro Hortelano”. Empresa Editora El Comercio, October 27, 2007, http://www.elcomercio.com.pe/edicionimpresa/html/2007-10-28/el_sindrome_del_ perro_del_hort.htmlGarcia, Perro Hortelano (accessed August 21, 2009).

- Gray, Andrew. 2002. “Indigenous Rights and Development: Self-Determination in an Amazon Community”. Quoted in Barrera-Hernández, Lila Peruvian Indigenous Land Conflict Explained. Council of the Americas, June 16, 2009. http://www.as-coa.org/article.php?id=1710 (accessed December 2009-January 20, 2010).

- Hearn, Kelly. “In Peru, Rainforest Natives Block Land Decrees”. World Politics Review, June 30, 2009. http://www.worldpoliticsreview.com/Article.aspx?id=4004 (accessed July 10, 2009).

- Interview with Alvan, Vicente. 2008. Interview by author. Yagua village near Pebas, Peru. December 26.

- Interview with Bora woman. 2008. Interview by Adam Ellison. Pucaurquillo, Peru. December 23.

- Interview with a curaca in the Huitoto tribe. 2008. Interview by author. Pucaurquillo, Peru. December 24.

- Interview with a teacher in the Bora tribe. 2008. Interview by author. Pucaurquillo, Peru. December 25.

- MBendi Information Services. http://www.mbendi.com/indy/oilg/sa/pe/p0005.htm#5 (accessed January 20. 2010).

- Nation Master. http://www.nationmaster.com/index.php (accessed January 23, 2010)

- Pantone, Dan James. The Bora Indians: Survival of a Native Culture. http://www.amazon- indians.org/page12.html (accessed August 20, 2009).

- Republic of Peru. Ministry of Energy and Mines. Petroleos del Perú- Petroperú s.a. http://www.petroperu.com.pe/portalweb/index2_uk.asp (accessed December 18-January 21, 2010).

- Taussig, Michael. 1984. Culture of Terror — Space of Death: Roger Casement’s Putumayo Report and the Explanation of Torture. Michael Taussig Comparative Studies in Society and History, Vol. 26, No. 3 (July), pp. 467-497.