Allan R. Staker and Professor Stanley Ferguson, Theater and Media Arts

When I applied for the ORCA Grant last year, I wanted to distribute a film project outside the boundaries of BYU and the University’s “FINAL CUT Student Film Festival.” In order to do so, I began to adapt the ideas pre-selling feature films to major studios that Professor John Lee taught in “TMA 389: Producer’s Practicum” to my own hypothetical process of selling a documentary series to a national cable network.

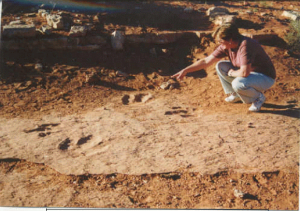

First, I needed some interesting material. My father, a petroleum geologist by trade, began last year to write a book about dinosaur tracks. A “Field Guide” of sorts, the book gathered into one volume a series of maps and images that would help other dinosaur fans discover these giant footprints for themselves. After consulting with my brother-in-law Marc Marriott, a film director, the three of us decided to expand the field guide to a documentary video, assembling an interesting montage of dinosaur tracks and the people who discovered them. We named our project, as well as the book which inspired it, “The Dinotrackers,” and decided to aim for distribution on the Discovery Channel.

Our idea, in its raw phases, had to first be evaluated for its target audience demographics and the strength of its campaign with regard to marketing strategies for attracting viewers. We figured that, with all the hype around the Disney animated feature film “Dinosaur” which was slated for domestic release in the spring of 2000, we could capitalize on the dino-hungry market by gearing the documentary toward a younger audience. Depending on the programming of the Discovery Channel and their specifications, however, we could likely adapt the project to whatever demographic they felt appropriate, simply by altering the personalities involved in narrating and explaining the tracks.

With this preliminary research under our belts, Marc, who lives in Los Angeles, contacted the Discovery Channel to learn how to go about our pitch. At their suggestion, he then contacted “Film Garden,” a production company in L.A. which assembles many documentaries for the Discovery Channel, Discovery Kids, The Travel Channel, and other related stations. Since he and I are relatively unknown as filmmakers, we decided we would be much better off attaching our project to an established company like Film Garden that already has good rapport with Discovery. Compiling all of our information, target audience research, proposals, images, and early editions of my father’s book, I flew to L.A., where Marc and I approached Film Garden and pitched them the idea.

The co-presidents of the company loved it. They were sold, and they offered several suggestions for improving our pitch before they took it to Discovery. Film Garden pitched our idea along with 23 others to the Travel Channel, who decided upon a group of shows involving water and beaches. We expected their response, and were not worried, as we envisioned the project airing on the Discovery Channel rather than its spinoffs. Film Garden promised to contact Discovery shortly thereafter, and our project was put on hold. After waiting several weeks without receiving word from the co-presidents of Film Garden, and following the advice of a different Film Garden contact, my father, Marc, and I decided to take matters into our own hands by assembling a more tangible pitch that Discovery couldn’t refuse.

Over the next several months, the three of us became Dinotrackers. We sought out the best known dinosaur track sites in Utah and Colorado, as well as the Dinotrackers who originally discovered them. We captured the sites and their amazing stories on video. We hiked through the deserts of Southern Utah, boated across channels in Lake Powell, visited fascinating museums in Price and uncovered new sites in St. George. Among the most interesting sites we visited was a coal mine outside of Price, Utah, were the minors had discovered footprints in the roof after extracting the coal. We contacted the mine and arranged for our own private expedition in order to capture the site on video. Unfortunately for other Dinotrackers, a nearby mine suffered an explosion only weeks later, rendering most of the Utah mines permanently inaccessible for tourists. We were not only lucky to be the first group of outsiders to see the tracks, but also to be the last tourists to ever set foot near the location. And we were fortunate enough to have our cameras rolling.

That brings us to the present. “Dinotrackers” is still in its early phases. There is another Dinotracking trip scheduled for two weeks from today, when we will visit a new site which must remain top secret at present. After that trip, all of the footage we have gathered will be edited together and submitted with our pitch to the Discovery Channel. If they like the idea, they will likely put up enough production funding for us to complete a one-hour pilot episode, after which they will determine its validity as a standing series. Should the Discovery Channel pass on the project, we will explore other options such as the History Channel, the Outdoor Life Network, etc. The three of us are confident that the show can be adapted to suit several target audiences, depending on how we go about filming it.

Although not yet complete, I feel that “Dinotrackers” is well on its way to distribution. Regardless of the success of this individual project, however, I feel I have gained, and will continue to gain, invaluable experience in expanding the audience of my films. Through this project, I have learned that the entertainment industry is more accessible than I once thought, and there is ample room for new filmmakers with strong subject matter and a good idea.