Jacob Z. Hess, Shelby L. Ferrin and Dr. Michael J. Lambert, Clinical Psychology

Psychological outcome measures are designed to measure the effectiveness of psychotherapy. The continued conversion of our health care system to managed care increases the need for such outcome instruments as insurance companies require therapists to have evidence that counseling is really helping a client. Initially, outcome measures were developed for adults; more recently, variations on these measures have been designed for children (Burlingame, et al., 1996). In this study, we compared two questionnaires designed to measure psychotherapy with children. Both instruments included a form for parents and a form for their child, from ages 12 to 17. Our comparison went beyond the crossinstrumental analyses to cross-generational comparisons. Previous research on the Y-OQ had shown differences in parent versus child ratings, but had not yet been replicated (Wells, 1999).

Across six months, the Youth Outcome Questionnaire (Y-OQ) and the Ohio Scales (OS) were administered at Wasatch Mental Health to 30 parent and child pairs who consented to participate in the study. Approximately 65% of those invited to participate accepted, while most of those who did not consent “did not have time.” The parent filled out the two parent versions; the teen filled out the two child versions, with the ordering of the two scales alternated to cancel out possible ordering effects. Most surveys were filled out prior to the intake session with a therapist, with a few being filled out soon after. Participants were given two dollars each in compensation for the extra paperwork time spent, and the additional questionnaire was available to their therapist for use in assessment. Initially, we planned to mail out the same surveys one month later; but after mailing out ten and receiving back only a few, we decided to focus on collecting data previous to the intake session only.

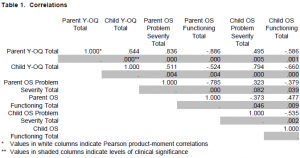

While the Y-OQ contains 64 questions in one section, the 72-question OS is divided into four different sections: Problem Severity (44 questions), Functioning (20 questions), Hopefulness (4 questions), and Satisfaction with mental health services (4 questions). The measures were hand-scored, with missing values replaced with the average of the respective sub-scale. After verifying that there were no outlying scores, all data were included. An SPSS data analysis generated cross-generational and crossinstrumental correlation data. Because of unequal numbers of questions in the different scales, totals were transformed into standardized Z-scores before correlation data was computed. Additionally, a paired sample t-test compared the means of parent and child totals for both measures. Reported means were significantly higher on both parent scales (Y-OQ=63.71, OS=33.00) than on the corresponding child scales (Y-OQ=57.88, OS=30.00).

Participating parents were 91% female, with 36% indicating they were married. Families tended to be larger, with 75% of parents reporting 4 children or more. Nearly half of all parents reported an annual income of less than 10,000 dollars; this however, may be due to some persons neglecting to report the income of their spouses. Most clients, however, were clearly under financial strain. Ninety-one percent of respondents were Caucasian, with three minority clients participating. The mean age and grade of the teenager was 14 years old in 9th grade.

Significant correlations were found between the Y-OQ as a whole and the Problem Severity and Functioning subscales of the OS (see Table 1). Moreover, correlations between the parent and child versions of the respective scales were strong. Within instruments, however, the Y-OQ showed a much stronger cross-generational correlation than did the OS. In fact, the correlations between the parent YOQ scales and child OS scales were stronger and more significant than the correlations between the parent and child scales on the OS alone.

This correlation study contributes to the literature investigating the validity of these two outcome measures. However, more research needs to be done comparing these measures with other more established measures. Such information may be helpful for mental health centers that administer outcome measures exclusively to parents and guardians, verifying that adult measures correlate with child measures. Our findings suggest that parents rate their children 3-6 points more severely than the child does. This harmonizes with previous studies on the comparison between parent and child selfreporting. Also, the Y-OQ appears to have a stronger relationship between parent and child versions, a result expected based on the greater number of questions.

References

- Burlingame, G.M., Wells, M.G., Hoag, M.J., Hope, C.A., Nebeker, R.S., Konkel, Kl, McCollam,P., Peterson, G., & Lambert, M.J. (1996). Administration and scoring manual for the Y-OQ 2.0. Stevenson, MD: American Professional Credentialing Services LLC.

- Ogles, B.M., Davis, D.C., & Lunnen, K.M. (1998). The Ohio Scales: A manual. Athens, OH: Southern Consortium for Children.

- Wells, G.M. (1999) Personal Communication.