Jon Balzotti, Assistant Professor of English

Evaluation of Academic Objectives

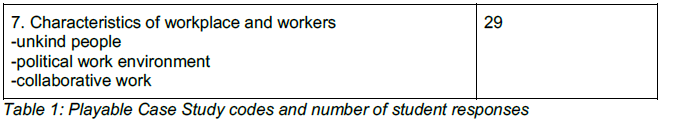

This project analyzed student engagement in a high school setting using digital learning environments based on a semi-realistic workplace simulation. The research team explored the challenges of high school student engagement in both traditional and digital learning environments. Data from student surveys suggest that traditional role-play in the classroom can be as effective as digital simulations in engaging student learners. While previous scholarship has focused on the advantages ARGs offer technical fields, very few have created short-term, adaptable simulations that take full advantage of the available technologies that people use regularly (texting, email, interviews through video clips, etc.) to explore critical thinking in secondary education. This collaborative research project developed, implemented, and assessed Alternate Reality Games (ARGs) as transformative tools for teaching literacy skills in middle or high school classrooms.

Classroom based simulations like the one created for this high school study invite students to make decisions consequential in real-life context, allowing them to see how the skills they learn may be applied in their future lives. The elements that create that authentic context are not exclusive to online PCS; by incorporating simulations that capitalize on real-life audiences, a variety of life-like evidence and complex situations that allow for a diversity of possible responses into writing assignments, teachers can help students connect their worlds with the academic world of school. In doing so, they navigate the space between student and teacher needs in the language arts classroom.

Evaluation of the Mentoring Environment

For this project we had the opportunity to mentor 3 BYU English students and 2 students from BYU’s Information Technology program. Jon Balzotti mentored a graduate student from the English department. The English graduate student used analysis of variance to compare learning experiences and writing products in the ARG with those of standard technical communication courses. We presented the results of our research at a national meeting with our primary research assistant as part of the panel. We then prepared and sent two journal manuscript for publication. Mentored English undergraduate students also helped to create the ARG. Jon Balzotti supervised 2 undergraduate students and one graduate student from BYU’s Rhetoric and Writing program, who in collaboration with students from the Information Technology Program, developed the online collaboration platform. Students had the opportunity to work on transformative projects that could set the stage for new models of classroom experiences. They worked on interdisciplinary, creative teams that included film-makers, graphic artists, and, of course, writers.

Results/Findings

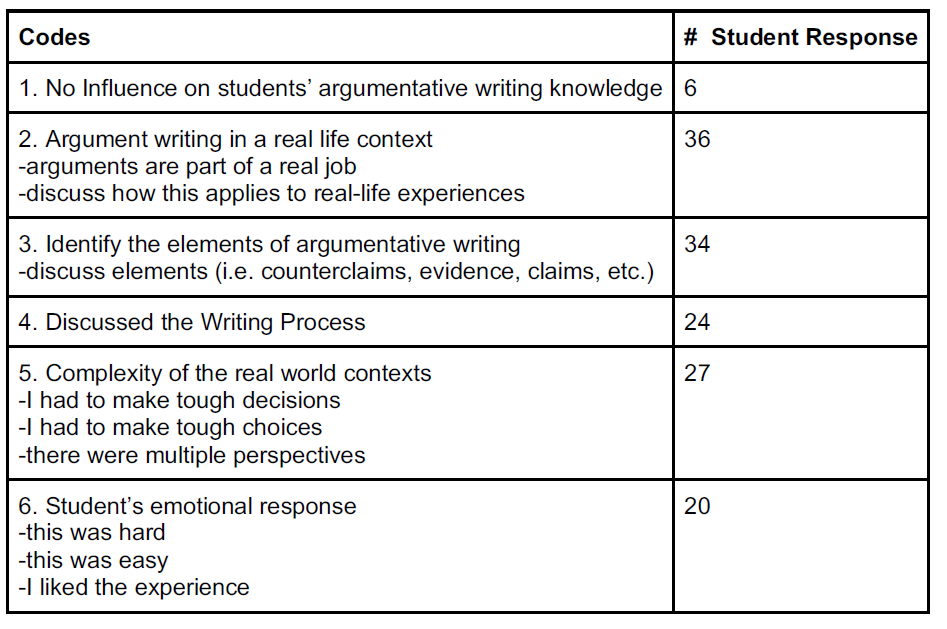

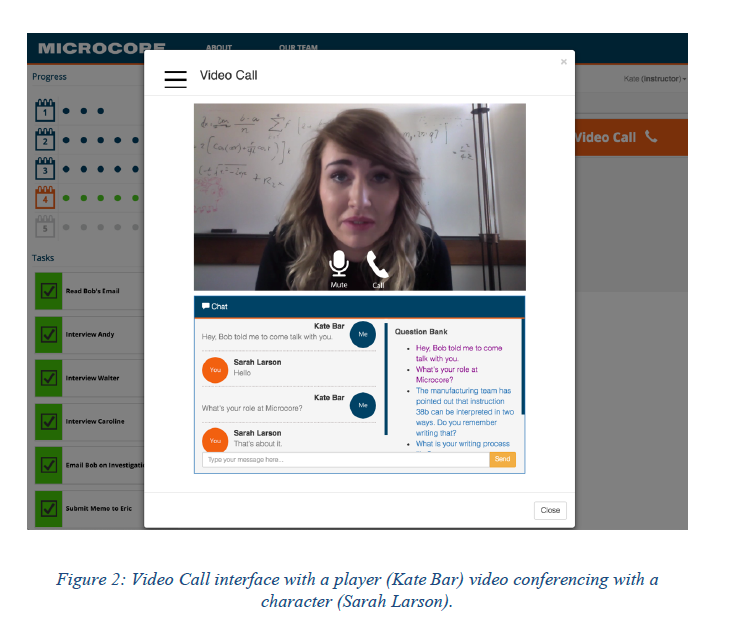

As we coded and analyzed student responses, the majority of students commented on elements linked to authenticity. Specifically, the real-life nature of the audience and context, the diversity of evidence types, and the existence of multiple possible solutions increased students’ perceptions of the relevance and authenticity of the writing experience as described below.

Writing to a Real Audience

Over half of students’ comments pointed to the authenticity of the workplace context and audience (i.e., fictional characters). They described enjoying the “real” and “very realistic” nature of the simulation, stating they felt it was “relatable to real life.” They also commented on the way their interactions made them feel like “real interns” as they made “real life” arguments in ways that went beyond regular assignments.

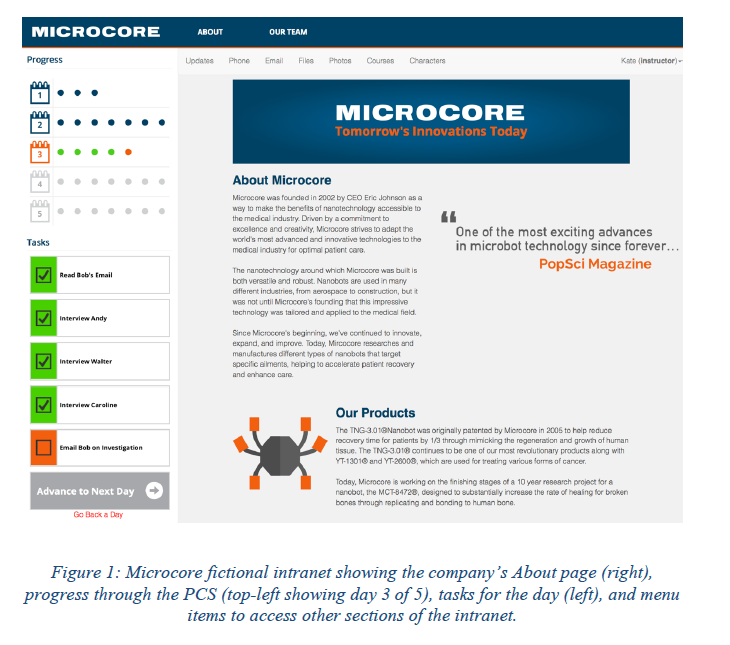

For example, Jessica explained, “The interviews [we conducted] made you feel like you were part of the company, also, they made me write emails for my supervisor and that made me feel important, like they are waiting for my response to move on to the next step.” She and others described how the interface increased authenticity, specifically mentioning “facetiming” (i.e., interviewing characters via video conferencing) and emailing their supervisor. These interactions with the characters made the embedded assignments feel purposeful and directed to an audience beyond the teacher. Classroom observers noted students complaining or praising fictional characters by name as if they were real people, as well as reflecting on how much they would love or hate working with various employees. Ms. Thomas made a similar observation and noted in her interview the discussions that resulted as the class tried to tease apart their emotional reactions to the characters’ personalities from the “facts” of the situation. These emotional connections influenced engagement as well as their approaches and attitudes towards the writing tasks.

The authentic context and audience also helped students make connections that helped them see how argument writing skills might be applied in actual workplace contexts. Marla explained “an argumentative essay can solve problems and help others understand your thinking,” and that it “needs to be more convincing” than when she is “writing for something of non-use.” Like Marla, many students recognized that argument writing would show up in real world contexts such as this and, therefore, the assignment would help them “learn potential skills for the future” and exist “not just for a grade.” Another student, Nadia, described her experience in this way: “In real workplace writing at Microcore I could write an argument as if I was really there and talking to these people. I learned how to get in other people’s head. It’s not out of an article it’s not boring facts, it’s a real-life situation.” For her, the simulation changed the way she constructed the argument because of the purpose and audience she wrote for.

These students and others described specific rhetorical moves they needed to make in their future workplace, such as speaking up, even when they disagreed with others’ perspectives; talking to their boss in specific ways and including enough evidence in a proposal to be convincing; and the importance of not just “throw[ing] together some random excuse for your boss and hope he buys into whatever you put together,” as they may do when completing typical argument writing assignments. Thus, students learned not only that argument writing occurs on the job, but also how to situate their writing into the rich social context and unique audiences within the workplace. When asked during class about lessons learned, students also mentioned professional skills such as “the need to be practical,” “serious,” “how hard we should work,” “the importance of being professional and doing a good job.”

Examining Authentic Evidence

In many argument writing situations, students begin with a thesis statement and then search for proof to support it. However, Hillocks explains that (2010) “good argument begins with looking at the data that are likely to become the evidence in an argument and that give rise to a thesis statement or major claim” (26). About half of the students discussed the way the simulation helped them rethink what qualifies as evidence as well as how the simulation caused them to use the evidence as the foundation for their argument.

First, the simulation expanded students’ notions of what “evidence” in a workplace argument might entail. They discovered that evidence comes in different forms— including emails, conference calls, spreadsheets, notes and observations—and commented on how these forms aided the writing process. Specifically, they described how the forms of evidence invited them back into the texts to re-examine different possibilities as they worked towards a conclusion. Anna explained, “It was a lot easier doing an argument paper when there’s a video of everyone saying what happened instead of reading a paper.” Other students benefited from the opportunity to immerse themselves in the scene. Belen stated, “Since I was able to see what was going on it helped me be able to argue about it and I could use real evidence instead of reading them.” Similarly, Rochelle explained, “Feeling like I was actually there helped me choose someone and have more backup evidence.” Ms. Thomas noted similar ideas as she observed students taking notes on the videos and commenting to her about how the videos helped them engage differently as they re-visited the material. These statements exemplify how the diverse forms of evidence made re-examining the evidence more accessible and helped students evaluate the relationship between the evidence and their claim.

Students also discussed how these different forms of evidence influenced the way they approached the writing process. Rather than first crafting a thesis and then finding evidence to support it, students realized they had to approach the argument as genuine inquiry. Johanna explained, “I learned that you need to be fully aware of all possibilities and be knowledgeable of both sides and you need to not make a biased decision.” Here she notes the importance of examining all positions and possibilities inherent in the simulation. Besides the multiplicity of possibilities, new evidence unfolded over time. In other words, as students returned to the workplace each day, they discovered additional information that clarified previous questions or complicated their assumptions, requiring them to examine and synthesize evidence as they developed their claims. In class, Barbara mentioned how the simulation helped her “keep an open mind” and not jump to premature conclusions. Classroom observations identified students who changed their opinion of which employee was primarily at fault based on new evidence that emerged. The nature of the task forced students to find and examine evidence surrounding the accident, make claims based on that evidence, and then to support their claims before ultimately coming to a conclusion. Because their ultimate recommendation would influence potential disciplinary action, students dug deep into evidence and, in the words of Tina, made them “pay attention to every little detail.”

In addition, the different types of evidence in the simulation helped students draw on the data to identify their claims. Students described the nature of evidence as “based off facts and not your own feelings.” Students alluded to the connection between evidence and research repeatedly, describing the process of conducting in-depth research to backup their claims. Alberto wrote, “For it to be a good paper you need several good points of evidence. Evidence that points right at who you are trying to put the blame on.” In each of these instances, the students’ notions of evidence expanded–they recognized the importance of examining multiple perspectives and considering facts.

However, students also recognized that fact and opinion are not easy to tease apart, particularly when much of the source data was gathered from employees with clear biases and competing explanations. While some students recognized the need to “keep my mind open to bias” and base decisions on facts, observations of the in-class discussions made clear that students’ initial response was often to blame the characters that were rude based off of their personality rather than the facts they provided. Ms. Thomas described class discussions that resulted from these reactions centering on how these emotional responses can cloud a fact-based analysis and the importance of basing their arguments on actual evidence evidence. This tension provided her with several opportunities to underscore the importance of critically evaluating evidence, the biases of sources, as well as the potential biases of students themselves.

Considering Multiple Possibilities

Over a quarter of the students in our study specifically mentioned the complexity of this writing task compared to others they did in school. Rory contrasted the nature of this argument with previous writing prompts she encountered: “Most argument essays I have to write are about liking or not liking a specific topic. For this one I had to think about four totally different things/people and you had to think more about the evidence and who was guilty.” Rory’s comments reflect the binary thinking of earlier assignments: “liking or not liking a topic,” and the new challenge of thinking about people, workplace problems, and multiple right answers to a problem. The intentional ambiguity of the Microcore problem challenged Rory and other students to evaluate different possibilities to the Microcore problem.

Many of the students mentioned how much they enjoyed the complexity of the workplace problem. Sam found it interesting and challenging to identify who was responsible for the pig exploding, commenting “It was what got my brain to think really hard as I was putting different pieces together with all the details I found. I continued thinking hard when putting together the argumentative essay.” In the teacher interview Ms. Thomas made a similar observation, explaining that student engagement in the discussions–both whole class and small group–increased on these days as students shared their findings from their own investigation and tried to unpack the different components that contributed to the accident.

The complexity of the workplace problem added additional difficulty while also allowing space for students to arrive at different conclusions. Kelly remarked on the balance he had to strike, acknowledging “You have to do some good research. I also learned to keep an open mind about which side to choose.” This open-mindedness and uncertainty in the students’ response to the problem caused them to attend to evidence and details their peers pointed out and to consider details they may have previously overlooked.

While most students enjoyed the complexity and ambiguity of the problem, some students strongly disliked it. During a classroom discussion of the simulation, Taylor mentioned his frustration with the assignment because “everything traced back to every person so it was hard.” Others complained that there was not enough information to figure out who was at fault, as if must be a single person. Indeed, after completing the survey on the final day of observations, a large number of students asked us to reveal who was really responsible for the pig explosion, a question Ms. Thomas explained they had posed to her previously throughout the simulation. We explained there was no single right answer (i.e. person at fault) in the simulation. Students admitted that this type of ambiguity mirrors the uncertainty in real-life arguments as well, adding authenticity to the situation. However, even as they acknowledged this authenticity element of the simulation, after learning the simulation lacked a single “right” answer many students expressed comedic exasperation.

The following comment by Alex aptly summarizes one of the most significant findings from our work with these students:

Instead of doing research on some random topic, I got to try out a real world problem. This will prepare me for the future, whether it is a property problem, job, or legal trouble. It gave me a new understanding of argumentative writing because it was an actual situation not just a teacher giving me a subject.

As teachers we know the importance of providing authentic writing opportunities to motivate our students, but they sometimes prove minimally effective for students like Alex and Brandon unless they see the authenticity of the writing task as well. To address the problem of authenticity, educational simulations provide unique opportunities that provide students authentic writing tasks.

In order to make this effective, students need to be able to depend on their shared experience in the classroom with their teachers and peers. Teacher-led discussions around the different elements of the simulation helped students in this study respond to real audiences. Similarly, the inclusion of real evidence distributed throughout the educational simulation was critical to student engagement, but understanding all of it required students to work with and listen to their peers’ observations and interpretations.

In addition, while students felt frustrated by a lack of a single “right” answer to the central issue in the simulation, they also reported this element made it feel “more real” than some of their other classroom experiences and assignments.

However, challenges arise when instructors are not accustomed to this type of teaching, and may require additional teacher preparation and support. Working with simulations in the classroom requires teachers to also teach and model collaborative problem solving and to embrace reciprocal teaching methods. Simulations, including computer-based ones, don’t function independent of the teacher; rather, like other meaningful teaching techniques they need to be teacher-supported and teacher-scaffolded.

Classroom based simulations like Microcore invite students to make decisions consequential in real-life context, allowing them to see how the skills they learn may be applied in their future lives. The elements that create that authentic context are not exclusive to online PCS; by incorporating simulations that capitalize on real-life audiences, a variety of life-like evidence and complex situations that allow for a diversity of possible responses into writing assignments, teachers can help students connect their worlds with the academic world of school. In doing so, they navigate the space between student and teacher needs in the language arts classroom.

Coding Dictionary