Aubriana Wolferts, Darren Hawkins, Political Science

Social proof treatments—informing people about the behavior of their peers—have generally been shown effective in influencing subjects to engage in behavior due to a psychological desire to conform.1 Social proofs are more effective when they describe what peers typically do rather than what peers generally approve of, and when the social proof is more salient and closely related to the desired behavior.2

While studies have shown social proof treatments to be effective in influencing the behavior of the general population, research to date has not yet assessed the impact of social proofs on government officials. In practice, social proof might motivate officials to take up new policy practices that benefit the citizens they serve. This study based on a randomized controlled experiment done in Peru explores the effects of social proof on government officials’ interest in learning more about using evidence to predict what policies and development programs might be effective. Invitations were sent to nearly 3,000 government officials to host a briefing in which researchers provided credentials for and coaching on a new online library reporting rigorous evaluation information on development programs. The library compiles and graphically summarizes results from more than 400 randomized control trials in international development. Such evidence-based reports (EBRs) have so far remained difficult to access for policy-makers without doctorates, despite their usefulness in indicating, using concrete evidence, what policies might be most effective. Any take-up of the invitations, therefore, would also have the practical advantage of promoting government learning of best practices in development programming.

Previous research indicates that a successful social proof must include two elements: (1) the social proof treatment should not normalize undesirable behavior, and (2) the social proof should be a descriptive norm that states what other people do, rather than an injunctive norm, which states what is commonly thought that one should do.3 Normalizing bad behavior encourages has been shown to increase participation in the undesirable behavior, producing results opposite of what was desired. Normative claims have been found ineffective at influencing behavior significantly. We carefully constructed our social proof treatment to adhere to these two best-practice social proof requirements. Half of the government officials were randomly assigned to receive the following social proof treatment in their initial invitation to hold a meeting to learn about the website library:

A number of your colleagues in [YOUR MINISTRY] have already expressed interest and have invited a meeting with us. In a recent survey of 6,750 policy-makers in 126 countries, information about successful public policy programs in other countries was ranked second in importance on a list of 14 policy inputs.

We have not found any literature that indicates that social proof treatments that adhere to the standards described above are ineffective. Therefore, we hypothesized that the social proof treatment would be effective in incentivizing uptake. Uptake was measured in four ways. First, the probability of receiving a positive response from a government official was evaluated. Any response that indicated interest in continuing the conversation about learning about the website was coded as positive. Second, negative responses were measured. A negative response clearly expressed disinterest or refusal to learn more about the website library. Third, meetings held were tracked and the probability of holding a meeting was evaluated in our analysis. Finally, the number of government officials trained in each meeting was tracked and evaluated.

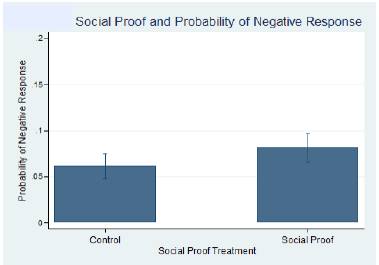

Surprisingly, we found that social proof had, at best, no significant effect on response and website usage rates and may have even increased the likelihood that government officials responded negatively to the request to hold a meeting to learn more about our website. The social proof treatment had no statistically significant impact on the likelihood of receiving a positive response or on the likelihood of holding a meeting. Furthermore, the social proof had no significant effect on the number of government officials trained in each meeting. Interestingly, the social proof treatment slightly increased the probability of a government official responding negatively to our invitation to hold a meeting. Government officials that did not receive the social proof treatment had a predicted 6.15% probability (95% confidence interval of 4.81 to 7.50) of responding negatively to the invitation to learn more about the website library. Those who were randomly assigned to the social proof treatment, however, had an 8.18% probability (95% confidence interval of 6.63 to 9.73) of giving a negative response. This difference is significant at the .1 level. These results are illustrated in Figure 1.

What might explain our surprising findings? One possible explanation of the null result is that elites react differently to social proofs than others might. Few social proof studies focus on elites and even fewer on elites in government positions.4 Previous studies indicate that persons classified as elite react differently when receiving advice and making decisions, and this could potentially explain their apparent resistance to the effect of a social proof.5 Elites have been shown to be less likely to listen to the advice of others and more likely to make decisions alone and on impulse.6 This could explain why the subjects of our study did not react positively to the social proof treatment. Rather than being motivated by the decisions of others, elites choose to form their own opinions and make their own decisions.

Another possibility is that social proof in the workplace induces free-riding. If employees hear that others in their ministry have received the same training, they may think it less important to spend their time doing it. They could rationally believe that their coworkers or supervisors will bring the issue to their attention later if it is actually important.

Our research indicates that social proofs, though shown to strongly impact behavior in other settings, do not have a significant impact on the behavior of Peruvian government officials, and may actually increase their likelihood of responding negatively to the request to engage in the desired behavior. More research, however, is necessary to understand if this result is a result of the social proof, or if there are other factors, such as free riding, that contribute to this result.

Figure 1 – Illustrates the effect of the social proof treatment—telling government officials that other officials in their ministry had expressed interest in meeting with us to learn more about a website library of evidence-based reports on development programs and policies—on negative responses. Contrary to our hypothesis and much of the literature on social proofs, the social proof treatment increased the likelihood that a government official would respond negatively to the invitation to meet with a research assistant to learn about the website library of evidence-based reports.

1 Cialdini, Robert B., Raymond R. Reno, and Carl A. Kallgren. “A focus theory of normative conduct: Recycling the concept of norms to reduce littering in public places.” Journal of personality and social psychology 58, no. 6 (1990): 1015.

2 Cialdini, Robert B., and Noah J. Goldstein. “Social influence: Compliance and conformity.” Annu. Rev. Psychol. 55 (2004): 591-621.

3 Cialdini, Robert B., Linda J. Demaine, Brad J. Sagarin, Daniel W. Barrett, Kelton Rhoads, and Patricia L. Winter. “Managing social norms for persuasive impact.” Social influence 1, no. 1 (2006): 3-15.

4 Rao, Hayagreeva, Henrich R. Greve, and Gerald F. Davis. “Fool’s gold: Social proof in the initiation and abandonment of coverage by Wall Street analysts.” Administrative Science Quarterly 46, no. 3 (2001): 502-526.

5 Galinsky, Adam D., Joe C. Magee, Deborah H. Gruenfeld, Jennifer A. Whitson, and Katie A. Liljenquist. “Power reduces the press of the situation: implications for creativity, conformity, and dissonance.” Journal of personality and social psychology95, no. 6 (2008): 1450.

6 Fast, Nathanael J., Niro Sivanathan, Nicole D. Mayer, and Adam D. Galinsky. “Power and overconfident decision-making.” Organizational behavior and human decision processes 117, no. 2 (2012): 249-260.