Elizabeth Whatcott and Dr. Joel Selway, Political Science

Within the United Kingdom, Scotland, Wales, and Northern Ireland have all gained regional assemblies which manage local affairs including health care, economic growth, education, and other services. However, the Parliament in Westminster has devolved few responsibilities to local authorities in England. Under the Blair premiership, the government began a process of referendums that would introduce regional assemblies into the Northern regions, but after the North East referendum rejected the proposal in 2004, the devolution process sputtered to a halt. However, regionalism may be gaining new life in England. The Yorkshire Party, a regionalist party that explicitly seeks a regional assembly for Yorkshire, was the first regional party established in the North.1 Others, such as the North East party, also seek to promote their region’s rights to self-government.

Our study sought to discover what sort of appeals to aspects regional identity can strengthen and politicize regional identity to the point where regions may start to support regionalist policies and organizations, such as regional parties and devolution movement. Though we administered the survey across the United Kingdom, this particular study focuses on Yorkshire as a potential hotbed of regionalist sentiment. We find that appeals to Yorkshire’s economic interests, regional history, and regional dialects encourage support for regional parties, and that economic appeals also strengthen regional identity strength.

Our study consisted of a survey administered online to 16,000 residents of the United Kingdom. This particular study, however, focuses on the 846 respondents who declared themselves as living in Yorkshire. In this survey, randomly participants read primes that included appeals to either British or Yorkshire identity. Each of these appeals highlighted a different aspect of that identity: regional or British history, regional or British economic interests, regional or British genetic heritage, and regional or British languages. A control comparison group did not read any appeals at all and saw instead a screen that invited them to continue the survey.

After reading the appeals or seeing the control screen, participants then gave answers to various questions about their support for regionalist policies and the strength of their regional identity. Participants thus indicated their support for devolving power to a regional assembly; their willingness to vote for a regional party, such as the Yorkshire Party; their willingness to support a regional language board that would protect regional dialects; and the strength of their regional identity compared to other identities that they have. We then compared the results of the respondents who had read regional or British appeals to the pure control group.

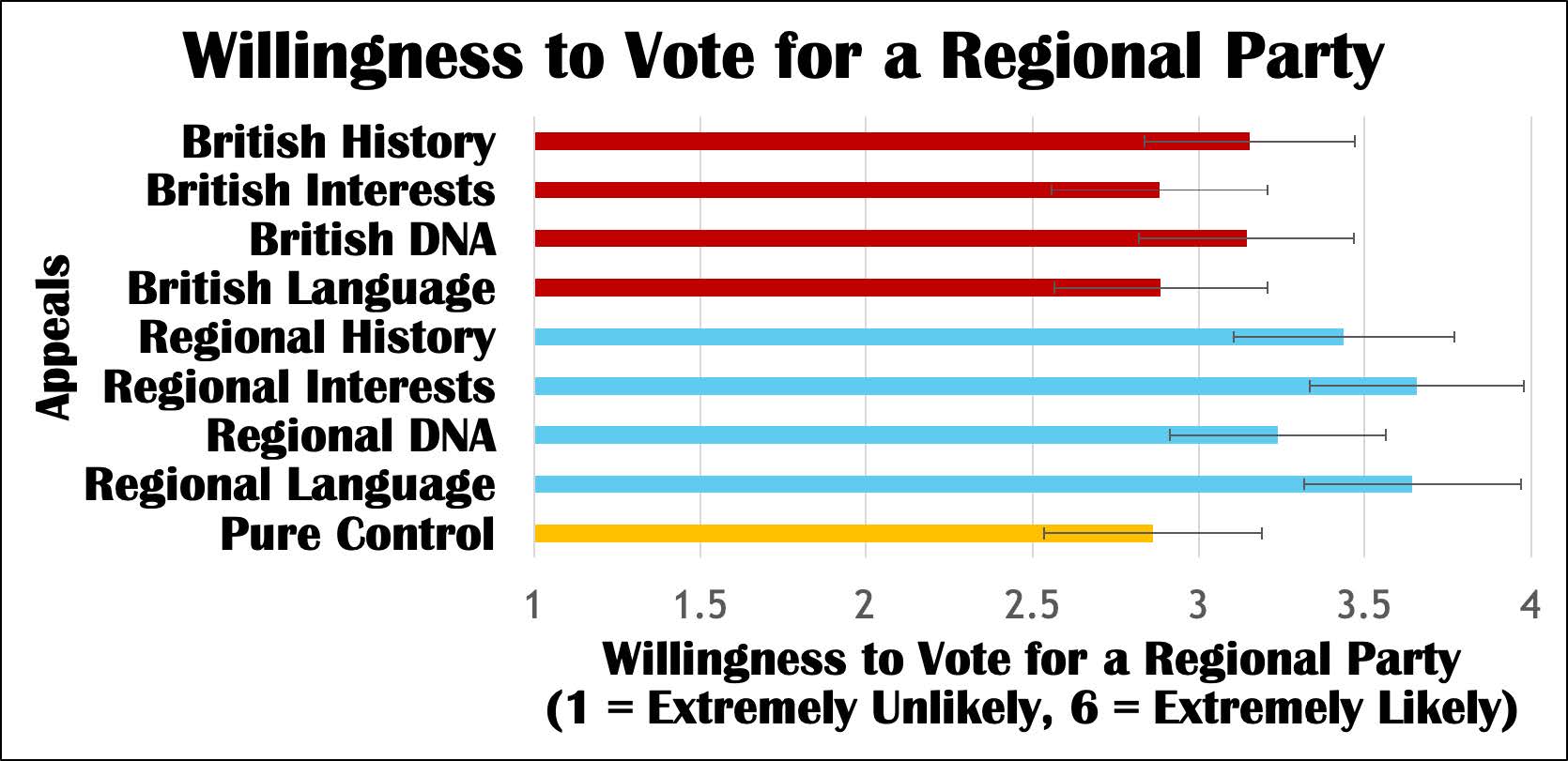

While none of the appeals were able to change support for devolution or a regional language board at a statistically significant level, some of our appeals did manage to change willingness to vote for a regional party. Regional economic interests increased the willingness to vote for a regional party by 0.797 points, regional language increased it by 0.750 points, and regional history by 0.639 points. Though not a huge increase in willingness to support a regional party, this does signify a potential jump from uncertainty about a regional party to more solid willingness to support a party like the Yorkshire Party.

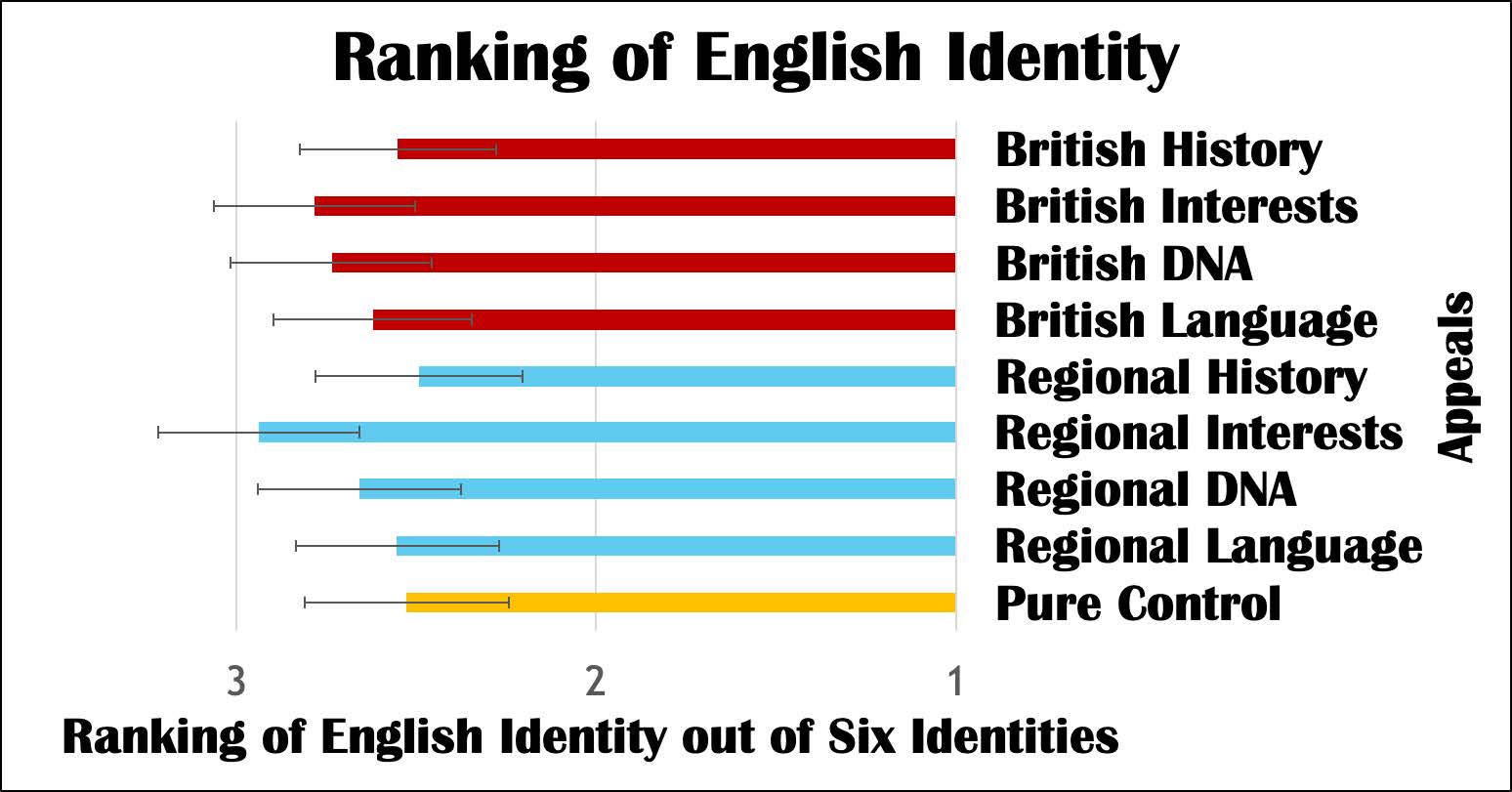

Appeals to regional economic interests also managed to shift the relative importance of the Yorkshire identity compared to other identities. When asked to rank a list of six identities by their relative importance, respondents who had received the regional interests treatment increased their ranking of their Yorkshire identity by 0.377 points on average and decreased the ranking of their English identity by 0.410 points on average. This suggests that these people essentially swapped the rankings of their Yorkshire and English identities, which according to the baseline usually fell at third and second place respectively.

The result showing that economic interests, historical ties, and linguistic heritage increasing regional party support lines up with the current practices of the Yorkshire Party and other regionalist parties. The Yorkshire Party focuses mainly on economic grievances unique to the region. As a hub of steel, wool, and coal production since the Industrial Revolution, Yorkshire has suffered in recent decades as industrial production has declined. However, the Yorkshire Party also uses distinct historical symbols and refers to ancient Yorkshire customs to make its case. More puzzling is the fact that economic interests have an effect on Yorkshire’s identity strength relative to English identity. Given that Yorkshire has a unique economic background which has bound the region in both boom and bust times, it seems that these unique regional interests have become tied to the region’s very identity. Thus, if regionalist groups such as the Yorkshire Party continue to drum up the economic grievances in the region, they could succeed at not only getting their candidates in office and their policies passed, but also could actually make people in Yorkshire feel more Yorkshire

1 Arianna Giovannini, “Towards a ‘New English Regionalism’ in the North? The Case of Yorkshire First,” The Political Quarterly 87, no. 4 (October 1, 2016): 590–600, https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-923X.12279.