Kaleb Norwald and Jake Thornock, Accounting

Introduction

Companies are sometimes required to pay taxes on events that have not yet occurred. This tax is called a deferred tax asset or DTA. These companies will receive a refund on this special type of tax, but the refund won’t be dispersed until years later. (Sometimes, this can take up to twenty years.) The slow reimbursement of a tax refund inhibits a company’s ability to grow, hire, and innovate as it unnecessarily constrains cash flow. Additionally, since this type of tax can be 7-13% of annual operating profits, the refunds are often very sizeable amounts.

The reimbursement process can be accelerated if taxing authorities and other decision makers have a better understanding of when these future taxable events will happen. Our research centers around understanding these future events and thus accelerating the tax-refund process.

Methodology

We retrieved our data from the Compustat database and used the SAS statistical program to perform our analysis. The companies we selected had DTA values for at least 6 consecutive years from 2002 to 2016. We used 2046 observations, including 217 companies from 9 industries. Data was scaled by total assets with a p-value of 0.05 considered significant.

We ran several types of mixed regressions with variables including: COGS (cost of goods sold), revenue, selling & administrative expenses, and accounted for the companies’ industry. We led, or offset, the data to determine how the variables from one year would affect tax reimbursements in future years. The regressions differed according to the number of years included and which variables were thrown out, as determined by our pre-regression analysis.

Results and Discussion

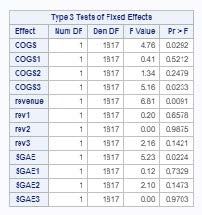

We determined that the variables that influence future refunds (or DTA values) the most significantly during the 2002 through 2016 fiscal years (long time horizon) were COGS, revenue, and selling and administrative expenses from the same year as the tax refund (Figure 1).

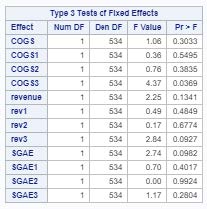

When using the same type of analysis for years 2013 through 2016 (short time horizon), the best indicators of tax refund (or DTA) value were COGS with a lead of three years (Figure 2).

Conclusion

We found it interesting that in the short-run the current year’s income statement has the best predictive ability in determining a refund three years in the future. This outcome was unexpected and will provide a starting point to begin accelerating tax refunds.

The long-run analysis was also surprising. We found that (A) the same year is most predictive of a future refund, which was not the case in the short-run analysis, and (B) that the third-year predictive ability begins to erode, except for the COGS variable. Thus, it can be determined that COGS is the most constant predictor of future refunds.

Overall, the predictive power of our model was not as predictive as we had hoped. We attribute this to the many legal changes that occur from year to year in the tax code and how the tax law affects each industry differently. We believe there is still a way to ascertain predictive value and, in the future, we will explore different models that account for these and other lurking variables.

Figure 1 – 2002 through 2016

Figure 2 – 2013 through 2016