Miranda Hatch, Connor Kreutz, Jessica Preece, Political Science

Introduction

Across the world, and especially in the United States of America, women are severely underrepresented in government. Although most Americans claim to see men and women as equals, covert and unintentional sexism still permeates the political decisions they make1.One consequence of this inadvertent sexism is the common perception that women are typically seen as less authoritative than men when it comes to politics. One way that this authority can be seen in politics is through endorsements given about candidates2.

Through our research, we sought to determine how the perceived gender of a political endorser impacts the survey participants’ likelihood of voting for and supporting the candidate he or she endorsed. We manipulated the perceived gender of an endorser through audio mechanics to obtain the same intonation and same content, but with voices that sound distinctly male or female. One subject group was randomly assigned to hear the endorsement given by a female voice and the other subject group listened to the same endorsement given by a male voice. We hypothesized that survey participants would be more likely to vote for and report more positive opinions for the candidate endorsed by a male. Through our findings, we hoped to identify, understand, and potentially prevent inadvertent sexism in the attitudes of the American political system.

Methodology

In order to test the perceived credibility that a woman has when compared to a male in politics, we executed our experiment by testing how the gender of an endorser effects political credibility. We used voice manipulation through audio mechanics to change a male recording to sound like a female. A man read a script endorsing first a male and next a female candidate. Our audio technician changed the voice to sound like a woman was speaking in each recording, the script includes facts and opinions about each candidate in hopes to persuade listeners to vote for that candidate. Other than the perceived gender of the voice, no other variables such as intonation or word emphasis were changed or manipulated. The four recordings are the following; male voice endorsing a male candidate, male voice endorsing a female candidate, female voice endorsing a female candidate and female voice endorsing a male candidate. After recording the endorsements, we created a Qualtrics survey and distribute it through Amazon Mechanical Turk service. Survey takers first answer demographic questions about their gender, political affiliation, education, age, and income. The participants were then randomly assigned to hear one of four recordings through the Qualtrics randomization feature. After hearing the robocall recording, they were asked to rate their support for a candidate on a 1-10 scale. They additionally were asked to answer questions about the competency, trustworthiness, and strength of both the candidate being endorsed in the call as well as the individual endorsing them.

Results and Discussion

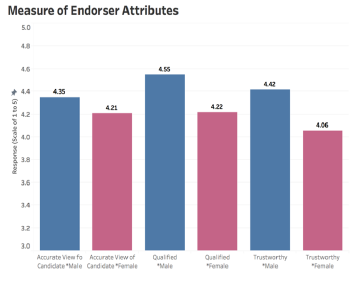

The results from our survey experiments confirmed our hypothesis that men possess greater political credibility than women. Both the male and female candidates were more likely to garner support from survey respondents when endorsed by a male than when endorsed by a female. They results were statistically significant, which suggests that the results found in our nationally representative sample of the U.S. population is very likely to be reflective of actual average sentiment held by Americans. Additionally, we found that when asked to rank candidates endorsed by males and females on a handful of character traits, subjects ranked candidates endorsed by men more competent, trustworthy, and non-partisan at statistically significant levels. Character evaluations of the endorsers themselves appear to be nearly as biased (see Figure 2).

The results of this research would suggest that Americans generally perceive men to be more credible endorsers of candidates than women, but we do recognize that this methodology is not without limitations. The design of this research cannot account for the appearance of any candidates or endorsers or the public’s general feeling towards them. It cannot account for their track record or any other factor not mentioned in their short biography.

Conclusion

Despite the noted limitations to our research, we are confident in the validity of our findings and in the important knowledge they create illuminating the role of sexism in political knowledge and credibility. The effect perceived gender and voice have on authority in politics raises questions about the role race, sexual orientation, and gender expression may also play in this same field. We recognize that studies alone will not change the standing of women in politics, but we hope that by making people aware of the effects of implicit sexism, we can help mitigate it in a small way.

Figure 1 – This figure illustrates the discrepancy in the rating between candidates endorsed by males and candidates endorsed by females. As seen in the figure, on average, candidates endorsed by males are rated more competent, non-partisan, and qualified. Each of these differences proved to be statistically significant at the 95% confidence level.

Figure 2 – This figure illustrates the discrepancy in the ratings between male and female endorsers. In every case, male endorsers were rated to have a more accurate view of the candidate, to be more qualified to endorse their candidate, and to be more trustworthy. The latter two measures show statistically significant differences.

1 Fingerhut, Hannah. 2016. “In Both Parties, Men and Women Differ Over Whether Women Still Face Obstacles to Progress.” Pew Research Center. August 16.

2 Bawn, Kathleen, Martin Cohen, David Karol, Seth Masket, Hans Noel, and John Zaller. 2012. “A Theory of Political Parties: Groups, Policy Demands and Nominations in American Politics.” Perspectives on Politics 10, no. 3 (September): 571–97.