Melissa J. Clayton and Professor Jerry L. Jaccard, Music

The task at hand, at the beginning of my research, was to discover the process of musical thought development in a child. Piaget’s similar research in mathematical thinking started with first discovering the content of children’s thought in mathematics, through clinical observation. Then he analyzed this content. He noticed changes at various points in a child’s growth. His observations and conclusions laid the foundation for a widely accepted theory. This theory is that children go through different stages of development as they learn (1). To discover the stages a child progresses through in attaining musical knowledge, I proposed to do research through which I would discover the content of children’s thoughts pertaining to music: the first step in Piaget’s method of research.

In looking for a way to examine the content of a child’s musical thought, I came up with quite a lengthy list of questions. Some of these were: To what degree does the music keep going in a child’s head when the audible sound had been turned off? When a child hears a song in their head, do they hear it as they were exposed to it? If they were first exposed to the song played on a certain instrument or sung by a certain voice, do the child hear in his/her head that instrument playing or that voice singing the song? Or, do they hear the song sung by their own voice? How do they, or do they visualize music in their heads? Each of these questions could have been a research project of its own. I needed to narrow my ideas to a specific question or find an over-arching principle that reached the heart of all of my questions.

At this point, I began a closer study of Moog’s findings (2). He had extensively observed the preschool child’s reaction to music as well as how they express themselves musically. In essence, he had done what I designed to do! His conclusion were interesting. It seemed that the developmental changes in the structure of musical thought coincided with the changing from one developmental stage to the next and that the underlying principle of these changes had to do with memory (2). Moog found that once a child moves from sensorimotor to preoperational, he can call up memory images. He can think and respond to things not present making “inner-combinations” or chains of thought (2). So development of musical thought may be based on these memory ability stages. At 18 months, movement (a sensorimotor response to a present stimulus) decreases and singing (a possible vocalization of music held in memory) increases (2).

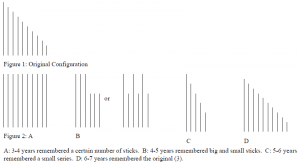

Here, I fortuitously ran across Piaget’s study in memory (3). Piaget presented children of different ages with a configuration of sticks which they were told to remember (Fig. 1). After one hour, one week, and one month they were asked what they remembered. The children remembered differently according to their age (Piaget categorized their responses, see Fig 2). The remarkable thing is that 74% of the children increased from one level of memory to the next between the one week and six months interviews. From this Piaget concludes that a memory-image is not merely a picture taken by the mind. A memory image “…acts in a symbolic manner so as to reflect the subject’s assimilation of ‘schemes’, that is, the way in which he understood the model (I say ‘understood’ , and not ‘copied’, which is an entirely different thing)…memory…is decoding of a code which has been changed, which is a better structure than it was before, and which gives rise to a new image which symbolizes the current state of the operational schema and not what it was at the time the encoding was done” (3). Memory in a “broad sense” is the “conservation” and use of structures (schema) with which we make sense of the world (3). As we develop, the schema change. They become more flexible and accurate. This is an over-arching principle in the study of thought development. The conservation of schema is intelligence. It is the means by which we think. Therefore, to understand the development of musical thought, I need to study the development of the structures of memory (schema) relating to music.

My mentor and I are proceeding to conduct an experiment that is a musical parallel to the experiment done by Piaget. Instead of presenting the children with a visual configuration, we will present them with a song. The song will be presented to three groups of subjects. The first group will only hear the song. The second group will be taught to sing it line by line, part to whole. The third group will be taught it as part of a game with movement. (In this variation we hope to ascertain whether motoric schema are involved in musical memory). At given intervals (one hour, one week, a six months) the levels of memory will be assessed.

References

- Ginsburg, Herbert and Sylvia Opper. Piaget’s Theory Intellectual Development. Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey: Prentice-Hall, Inc., 1978.

- Moog, Helmut. The Musical Experience of the Pre-school Child. translated by Claudia Clarke. London: Schott & Co. Ltd., 1976.

- Piaget, Jean. On the Development of Memory and Identity. translated by Eleanor Duckworth. Barre, MA: The Barre Publishing Company,1968.