Nicole Gomez Bravo and Laura Smith, German

Introduction

This study examined factors influencing the linguistic and cultural integration of Spanish-speaking immigrants into the local language and culture. Immigration and the integration of recent immigrants is an increasingly polarizing topic worldwide, with many citizens complaining that new immigrants fail to learn the target language of their new home and refuse to integrate into local culture. Consequently, immigrants from some cultures often face discrimination or poor treatment. In the United States, immigrants from Spanish-speaking countries in Latin America are one such group encountering well-publicized difficulties. Spanish-speaking immigrants are also on the rise in German-speaking countries such as Germany and Austria, where these immigrants are seeking better economic opportunities available there. While many of these immigrants come from Spain, a number are also coming from Latin America via Spain.

Research Questions

RQ1: Is the experience of Spanish-speaking immigrants different in Germany and Austria than in the U.S. in terms of cultural and linguistic integration? In particular, are they more, equally or less likely to learn the local target language and associate with native speakers of the target language, i.e., German or English.

RQ2: If there are differences between immigrants in German-speaking countries versus the U.S., what might be the sources of those differences?

Anticipated Results:

Since Europeans are more accustomed to speaking multiple languages than their American counterparts, we anticipated that Spanish-speaking immigrants would find it easier to assimilate into the local language and culture in Germany than immigrants in the United States. This expectation is also in part due to an increase in EU citizens from Mediterranean countries learning German and moving to Germany for employment opportunities. Our expectation is also driven by the fact that there are higher numbers of L2 Spanish-speakers in the United States able to help Spanish-speaking immigrants.

Methodology

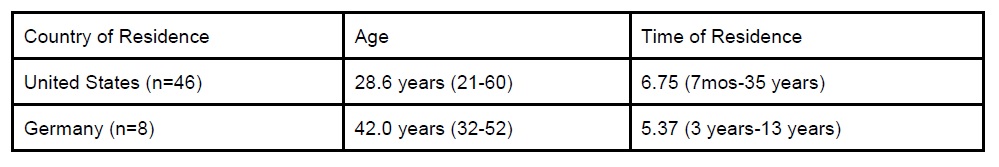

Subjects: To participate in the study, respondents needed to have lived in their country of residence, Germany or the United States for at least 6 months, preferably more than 1 year (cf. table below for overview). Most subjects in both the U.S. and Germany were from Latin America. Only one subject in each of the US and Germany had grown up in Spain; however, 7 out of 8 subjects in Germany had double citizenship with Spain despite growing up in Latin America. A substantially smaller number of respondents participated from Germany in part due to the length of the survey as well as concerns about privacy, an important issue in Europe. Since our survey represents a convenience sample, i.e., those who were willing to help, results must be taken with caution.

Questionnaire:

Surveys were administered to Spanish-speaking immigrants living in Germany and the United States. Both surveys were basically the same but tailored to the specific target language and country. Surveys collected data on topics such as time of residence, reasons for immigration, educational background, work, family relations, languages used at work and home, language learning, as well as self-reporting on issues such as comfort with the target language, cooking local food, integration into the target community, activities they participate in outside of the home, etc.

Preliminary analysis of data:

Survey responses for questions using Likert scales were analyzed in terms of inferential and descriptive statistics, using in particular a series of one-way ANOVAs. Information regarding their educational level, age, country of origin, work life, etc. served as independent variables for assessing these Likert responses. Open-ended questions on the survey as well as responses from the interviews were assessed via qualitative analysis to determine recurrent themes regarding the experiences of the respondents in their respective countries.

Preliminary Results* (full statistical reporting not given due to space constraints; available upon request)

Results of a series of one-way ANOVAs comparing responses from subjects in Germany vs. the United States revealed significant differences across a number of factors and perceptions demonstrating more favorable experiences for Spanish-speaking immigrants in the United States overall: there are a larger number of jobs in which Spanish can be used in the United States (p< 0.001); U.S. respondents felt less timid speaking target language (English in the US vs. German in Germany) (p<0.001); U.S. respondents found it easier to find Spanish-speaking social groups (p<0.001); the Spanish community was larger in the U.S. (p<0.001) with a larger number of Spanish-speaking businesses (p<0.001), more frequent local Spanish-speaking activities (p<0.001), despite less frequent participation in Spanish activities (p=0.024) and less likelihood to seek out Spanish activities (p=0.011); U.S. respondents also put more importance on seeking out activities in the local language (p<0.001) and assimilating into target culture (p=0.031). They also found it easier to make friends from target culture (p=0.014), self-reported higher proficiency in the target language in terms of speaking, reading, understanding and writing (p<0.001). U.S. respondents were also more motivated to learn the target language (p=0.041) and viewed English as easier to learn than their German counterparts found than learning German (p<0.001). Lastly, U.S. respondents rated locals as more patient than their German counterparts (p=0.030).

Additional one-way ANOVAs were run to determine any additional effects based on the education level of respondents as well as reason for immigration (education, family or work) regardless of country of residence. Level of education was found to significantly impact self-ratings for understanding (p=0.003) (alongside approaching levels of significance for speaking (p=0.094) and reading (p=0.080), where higher levels of education were found to correspond to higher self-ratings. Interestingly, the reason why subjects immigrated was found to be significant for the following: it was easier to find friends from the target culture ((p=0.01); where it was easier if they came for education or family than job); if respondents came for education, they were more likely to report wanting to integrate into the local culture (p=0.034); and self-reports of language ability across all domains, motivation to learn the language, perception of how easy the language was to learn were significantly impacted by the reason for which immigrants came. In sum, those who immigrated due to education or family gave more favorable responses than those who immigrated for job opportunities. Two-way ANOVAs were run to determine any interactions between country of residence and either education level or reason for immigration; no such interactions were found.

Qualitative analysis of open-ended questions and interviews also revealed that most immigrants in the U.S. would like to become American citizens while those in Germany are less interested in citizenship there since they have Spanish citizenship and can work and study freely in Germany. During interviews, respondents noted that although they had not themselves experienced discrimination, they noted that they had seen other Spanish-speakers who were not as proficient in the target language be subject to discrimination. Moreover, Spanish-speaking immigrants in the U.S. self-report higher levels of English proficiency than their counterparts in Germany report German proficiency.

Discussion

Results of this survey did indeed demonstrate a difference in responses between Spanish-speaking immigrants in the U.S. and in Germany. However, contrary to expected results, Spanish-speaking immigrants in the U.S. reported more favorable conditions for linguistic and cultural integration than their German counterparts. Although the U.S. immigrants had more Spanish cultural and linguistic opportunities, these seemed to be accompanied by a better opportunity to integrate into American and English-speaking cultural circles that education alone could not account for. The common denominator across responses appears to be that pre-existing language proficiency is a critical door to integration into the culture and more willingness to participate in the local culture, something that appears to be higher in the United States than in Germany despite the well-publicized difficulties Latin American immigrants are currently experiencing.