Charles Dale Flint and Emily Darowski, Harold B. Lee Library

Introduction

Ambivalent sexism is present in U.S. university students (Chrisler, Gorman, Marvan, & Johnston-Robledo, 2013) and is a combination of both hostile sexism (a direct antipathy towards woman) and benevolent sexism (seemingly positive beliefs and actions based on gender stereotypes; Glick & Fiske, 1996). Ambivalent sexism is associated with justifying sexual assault and placing blame on victims (Koepke, Eyssel, & Bhoner, 2014). Similarly, high levels of sexual prejudice, or negative attitudes towards others based on sexual orientation, and rigid views of masculine gender roles, are associated with increased aggression and anger towards members of the LGBTQ+ community, hate crimes, and other antigay behaviors (Parrott, 2009; Herek, 2000). Previous studies have measured changes in student attitudes related to gender and found a decrease in levels of sexist and prejudiced attitudes after taking related psychology courses (Pettijohn & Walzer, 2008; Livosky, Pettijohn, & Capo, 2008). While these studies were conducted at religious institutions, the effect of these courses on levels of religiosity were not measured. The present study sought to replicate and extend this research. Our study was conducted at a private, religious university and measured differences in gender role ideologies, levels of ambivalent sexism, and sexual prejudice in students enrolled in a psychology of gender course compared to students enrolled in a writing within psychology course (e.g., control group). Religiosity was also measured. We predicted that compared to the control group, students in the psychology of gender course would have decreased levels of sexism and sexual prejudice, expanded views of gender roles, but steady levels of religiosity.

Methods

On the pretest, one participant chose not to complete any surveys and another did not specify which class they were in; both were removed from the data set. We had 11 participants complete the pretest survey and 7 participants complete the posttest survey in the psychology of gender course. Of these, 4 took both the pretest and posttest, making a total of 14 participants from this course (78.6% female). Students were 78.6% White, 14.3% American Indian or Alaska Native, and 7.1% Pacific Islander or Native Hawaiian. Psychology of gender course participants ranged from 20 to 24 years old (M = 22.5). In the writing in psychology course, 22 participants completed the pretest survey and 12 completed the posttest survey. Of these, 6 took both the pretest and posttest, making a total of 28 participants from this course (75% female). Students were 96.4% White and 3.6% Pacific Islander or Native Hawaiian. Writing within psychology participants ranged from 18 to 26 (M = 20.6). Two participants did not complete one or more surveys but were still included in relevant analyses.

Students were recruited by a member of the research team visiting each class and handing out flyers with links to the survey. Recruiting took place in the first two weeks and last two weeks of the semester. At each time point, participants were asked to provide implied consent and then respond to a survey made up of a demographics questionnaire and four different assessments: the ambivalent sexism inventory (ASI; 22 items, 6 point Likert scale), the gender ideology scale (GIS; 18 items, 7 point Likert scale), the sexual prejudice scale, (SPS; 18 items, 6 point Likert scale) and the religious commitment inventory (RCI; 10 items, 5 point Likert scale) (Chonody, 2013; Glick & Fiske, 1996; Hahn, Banchefsky, Park, & Judd, 2015; Worthington et al., 2003).

Results

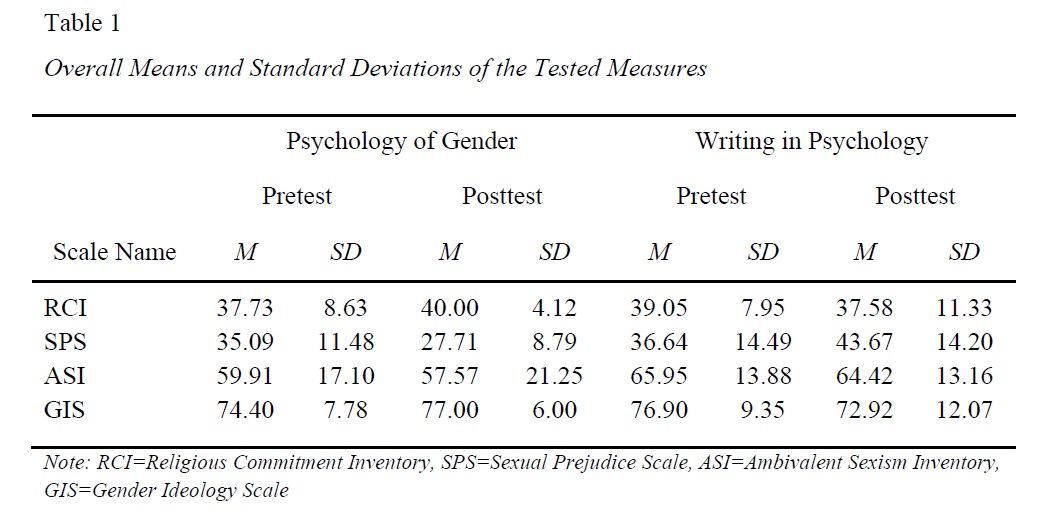

Table 1 shows overall means and standard deviations on the tested measures. Independent t-tests were conducted to compare overall means between the pretest and posttest for the psychology of gender course participants; all ps were greater than .167. Independent t-tests were conducted to compare overall means between the pretest and posttest for the writing within psychology course participants; all ps were greater than .183. Independent t-tests were also run to compare the differences between the psychology of gender participants and the writing within psychology participants at pretest; all ps were greater than .289 Finally, independent t-tests were conducted to compare the differences between the psychology of gender participants and the writing within psychology participants at posttest. The difference between the two groups on the SPS was significant, t(17) =2.671, p =.016. Psychology of gender students rated themselves lower on sexual prejudice than writing within psychology students. All other ps were greater than .395.

Discussion

Our results were overall inconclusive due to low sample size and the inability to run within subjects tests because very few students took both the pre- and posttest. These major limitations seemed to result from lack of response to our recruiting methods. An examination of the means suggests that sexism and sexual prejudice was trending downward in the psychology of gender students, whereas religiosity was trending upward. Although equivalent at the pretest, psychology of gender students reported lower levels of sexual prejudice at posttest compared to to writing within psychology students. Further studies, with higher power, are needed to establish evidence about whether taking a psychology of gender course decreases levels of sexual prejudice and sexism and changes views of gender ideologies in students. Further examination of religiosity in this context is also needed.