Nichole Christensen, Jessica Preece, Political Science

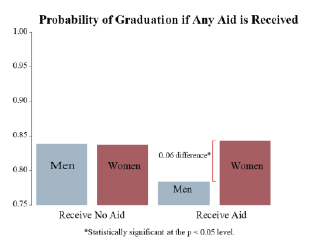

We analyze how being a federal financial aid recipient contributes to a person’s likelihood of graduation. We theorize that women who receive financial aid will be more likely to graduate than men who receive financial aid. This hypothesis can be viewed as a test of whether or not the economic development literature, which is primarily tested in Third World countries, may apply to First World settings. We also theorize that females who receive financial aid are more likely to graduate than both females and males who do not receive financial aid. We began by using the simplest model possible by regressing if a person had “completed degree/course of study” on gender. The results were statistically insignificant. Such a finding seemed odd as much of the current literature and data indicate that women are graduating at higher rates than men are (Executive Office of the President of the United States 2014). The simple answer to this is to look at the longitudinal data on graduation rates. This 1987 data fits into the time period where most data indicate that men and women graduated at statistically the same rate. The consistency between existing literature and data on graduation rates in 1987 works to support the claim that our data set, although limited, is valid. The lack of statistical difference in the gender variable in the simple model adds intrigue as it becomes significant in the simple model that tests our theory. In this logistic model, we added the interactive term of “Female and Any Aid.” Here, we see that women have statistically different logged odds of graduating or completing their study than men given they receive any financial aid. Additional models support the claim that women with financial aid graduate at higher rates than men do with financial aid. The simplest of these models shows that females receiving financial aid have an 84 percent likelihood of graduation, while males have a 78 percent likelihood of graduation. This 6 percent is statistically significant. Another model shows that after including all relevant controls, women receiving aid still have statistically significantly higher logged odds of graduating. Subsequent models only contain those that received financial aid, and control for how much aid was received and the total cost of one year of schooling, the gender variable becomes more telling of our theory. Every model except one shows that women have higher logged odds of graduating than men given that both are receiving the same amount of financial aid and their schooling costs the same.

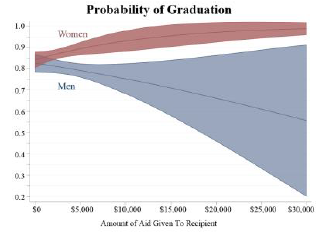

The median amount of aid given in this data set is $2,370. A female student with the median amount of financial aid has, according to our results, 86.7 percent likelihood of graduating from college, as compared to females in the 25th percentile of aid (85 percent likelihood of graduation) or females in the 75th percentile of aid (88 percent likelihood of graduation). Realizing that the coefficient of “Aid Amount” will change by hundreds and thousands helps us understand the substantive effect is more than initially indicated by the small coefficient. We find many noteworthy factors relating to likelihood of graduation. Among women, the amount of aid given significantly increased the likelihood of graduation. In both the simplest and most comprehensive models, we find that females with aid are more likely to graduate than females without aid and males, both with and without aid. This is our most substantive finding. It seems the data from the 1987 National Postsecondary Student Aid Survey support our hypotheses that women use student financial aid more effectively than men do. Concluding that women use student financial aid better than men do supports the economic development literature referenced above. Wong and Psacharopoulos appear to support the idea that women use resources more effectively than men do by showing how children improve when the woman has control of the income. We argue that this theory is not limited to development economics. We find evidence to suggest that the same theory is true in higher education aid within United States. The implications of these results reach into both practical and academic spheres. For the institutions deciding who gets student financial aid, the results of these analyses may be particularly helpful. For academia, this study may aid in increasing the external validity of some gendered economic development theories.

Figure 1 is conceptually important to our theory. Here, “Aid Amount” is added to the model. Doing so filters the observations to only those that received some aid. Of those who receive aid, women are statistically more likely to graduate than men.

Figure 2 shows the probability of graduated of students depending on the amount of aid they received. As the amount of aid increases, the probability of graduation does not statistically significantly change. Despite this, women are still more likely to graduate than men.

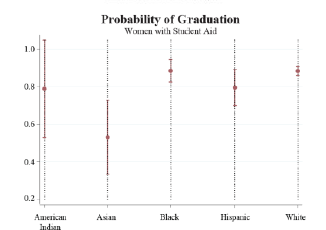

Figure 3 shows the significance of race on graduation. Hispanic is significant in all models where race is included. Among women, Hispanic is not as significant until income is considered. The data seem to indicate that Hispanics have lower logged odds of graduating when compared to whites. The other piece of the race variable that comes out significant in every instance is Asian race.

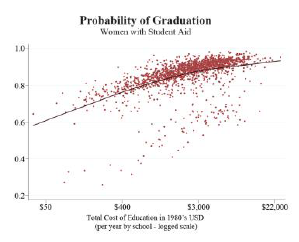

Figure 4 shows the significance of the cost of schooling. Interestingly, as the total cost of a year of school goes up, the woman is more likely to graduate. This finding also appears to be true for men, as this control is statistically significant in all models as well. One possible explanation for this trend is that only people that have the means and drive to finish a degree choose to attend a more expensive school. Those that question if they have the time, resources, or drive to finish would logically not risk as much money by attending a more expensive program. It is likely that those attending the more expensive school are systematically different from those that attend the less expensive schools.