William Oldroyd and Dr. Jani Radebaugh, Geology Department

Meteorites are essential tools for understanding early Solar System dynamics, composition and formation. Models used to study the early Solar System rely on meteoritic composition and relative abundance of samples collected. Meteorites with high specific gravities, such as iron and stony-iron meteorites, appear to be underrepresented in Antarctic collections over the last 40 years. This underrepresentation is in comparison with observed meteorite falls, which are believed to represent the actual population of meteorites striking Earth, and hence, the composition of material in our Solar System. Our research is focused on determining probable equilibrium depths of meteorites beneath the Antarctic ice so that future collection efforts may incorporate this hidden population into their search.

Over the lifetime of Earth, meteorites have gradually accumulated in the Antarctic ice sheet and have become buried. As the ice sheet flows from the center of the continent towards the ocean, meteorites are transported and are eventually deposited on the seafloor. Occasionally, however, the flow of the ice sheet is impeded by a mountain range and leaves meteorites stranded at the mountain margins. The flow then pushes the meteorites towards the surface aided by ablation, which is the removeal of ice from the surface. In opposition to this upward force, meteorites on the Antarctic ice sheet absorb solar flux, leading to downward tunneling into the ice. Observations of this process in action are very limited, hence the need for modeling. Meteorites that both absorb adequate thermal energy and are sufficiently dense may sink back down into the ice and reach a shallow equilibrium depth as downward melting overcomes upward forces during the Antarctic summer. Using solar flux data we collected during two seasons in the Antarctic deep field (2013-14 and 16-17), we are mathematically modeling the thermal interactions of meteorites with their Antarctic environment in response to solar heating, taking into account a wide range of parameters.

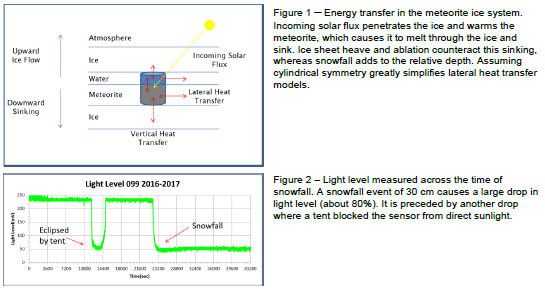

Using a pyranometer, we obtained solar flux measurements at varying depths in two deep field sites in Antarctica. The results of our measurements are used to determine the amount of thermal energy absorbed by meteorites and their surroundings. Our model accounts for incoming solar energy absorbed as a function of albedo, surface area of the absorbing face, and total incident solar flux (which is measured light level times a calibration factor); radiative heat transfer between the meteorite and the ice as a function of their temperatures, ice and meteorite emissivity and the surface area of the absorbing face; vertical conductive heat transfer as a function of temperature, depth, vertically oriented area and thermal conductivity; and lateral conductive heat transfer assuming cylindrical symmetry as a function of temperature, distance from the meteorite, thermal conductivity and meteorite height as well as various other parameters (See figure 1).

During the 2013-14 meteorite collection season we measured the light level at depths of 0, 20, and 45 cm in Antarctic snow. For the 2016-17 season depths of 0 and 30 cm were observed. As shown in figure 2, this amount of snowfall is sufficient to drastically reduce the amount of solar flux and, hence, energy available for a meteorite to use to melt through the ice. From our models we see that a threshold temperature must be reached in order for a meteorite to tunnel through the ice. The amount of energy received by a meteorite is directly proportional to its ability to reach this threshold, which is highly dependent upon initial conditions, and melt down through the Antarctic ice.

Our data give insight into the effect of snowfall on solar flux received by subglacial meteorites. Based on the large drop in light level, which is proportional to energy, caused by a few centimeters of snow cover, it appears that buried meteorites receive less solar energy than previously expected. While the snow is quickly ablated in comparison to the ice sheet, it does provide temporary cover which reduces the overall energy that can be absorbed by a meteorite in Antarctica. Since the snow layer is short lived, it can be assumed that it adds very little long-term depth for the meteorite, but substantially reduces energy received for a time. Hence, if a subglacial population of iron meteorites exists, it may be more shallowly buried than previously thought. We intend to continue the modeling process over the next few months in order to obtain more precise values for predicted meteorite depths under a variety of conditions.

The relative abundances of meteorite species shape our understanding of Solar System composition and formation. They developed early on and are one of the only remaining features of the early Solar System. The discovery of additional meteorite populations would change our estimates of primeval solar system composition ratios. Based on our solar flux measurements coupled with our models, snowfall has enough of an impact on incoming solar energy available to a subglacial meteorite that these undiscovered populations may be closer to the surface than previously thought.