Matthew Harrison and Faculty Mentor: Brian Pierce, Spanish and Portuguese

For as long as we have recognized the existence of music, it has been inevitably and

profoundly representative of our world’s many diverse cultures. By chance, just the other

week I had the opportunity to chat with some family members about the origins of

modern hip-hop music in the United States; it was fascinating to not only agree upon

some wide-spread fundamental influences such as the classic rhythm and blues of Ray

Charles and the boundary-pushing synth tunes of Kraftwerk, but also to recognize that

while pulling from these influences, modern hip-hop has become something entirely of its

own. The influences of older music genres in conjunction with the experiences lived by

the artists themselves creates something worthy of our scrutiny.

Hip-hop music, though generally associated with its beginnings and subsequent

developments in the United States, has proven to be a significant means of global musical

expression that resonates especially within youth culture. While preparing a proposal for

our project, Dr. Price and I found ourselves quite fascinated by the prospect of researching

hip-hop music in the Andean region of South America. Through online research we

became aware of a plethora of musicians in El Alto, Bolivia that were expressing

themselves through hip-hop music. Their inclusion of the indigenous Aymara language in

their rapping seemed significant, and we were also interested by the fact that they use

what many people consider to be an American art form to express ideas that oftentimes

are anti-American. Finally, from what we had initially read and seen of the artists, they

seemed to share a unique sense of comradery in commenting on the world around them

and in making their immediate environment a better place in which to live. We believed

that there was still a lot to learn from them.

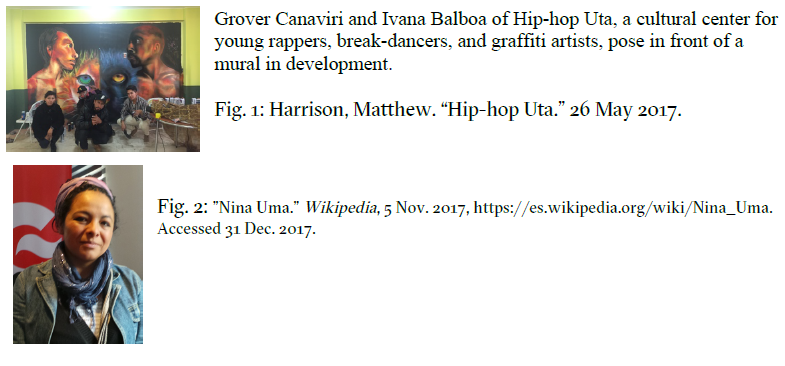

The study promised to yield results in the field of ethnomusicology, and as such, we hoped

to receive clues and insights into the culture and sociality of the artists in question and the

people they represent. We started to reach out to multiple artists through social media, but

did not have any luck with regards to their reciprocation. However, I planned to directly

arrive in Bolivia, and from there it was not hard to find hip-hop musicians in cultural

centers and gain their trust. We then received contacts of other musicians, and we ended

up with audio recordings of interviews conducted with five rappers, a highly

knowledgeable radio host, and the head of a new hip-hop based cultural center in El Alto

(see Image 1). We also received six local hip-hop CDs from the artists themselves that

contain lyric sheets.

In order to elaborate upon some of our findings, I will detail a specific interview that I

conducted during my visit. Through my interactions with Santos, the host of a popular

radio show on 101.7 FM in El Alto, I was able to receive the contact of Nina Uma, a

prominent voice both in the hip-hop scene in El Alto and in local activism (see Image 2).

For her, the two things go hand in hand. She uses her music to express the concerns of her

community, her worries with regards to the environment, and to take a stand on certain

political issues, though she makes a concerted effort to not take sides. In our conversation,

she argued that there is an “individualistic thinking to which all of modern society is

pushing us, and it is centered around competition and the individual: one person alone.”

Her statements and her music echo a Bolivian motto found on their currency, which

states, “La unión es la fuerza” – unity is strength. However, she also argues that there was a

lacking in the higher education she pursued in her adulthood: “at a certain point you

realize that what they teach you in school, what they teach you in the university, doesn’t

tell you what’s really happening.” She has made it her goal to educate those around her,

and her mindset is contemporarily based.

Nina Uma is not alone; the other musicians interviewed, though many of their opinions

differed, shared the hope that their music can make a difference. They have taken a

particular aspect of traditional hip-hop – its activism – and made it a focal point. They

respond to unique situations that rappers in other contexts have not experienced.

Upon returning to the United States, I began the process of transcribing the interviews

that were conducted, including that of Nina Uma. In total, we now have over 24,500

words of interviews that will help us to better understand the social and political

landscapes in which the younger Alteño population find themselves. Along with Dr. Price,

we are still in the process of analyzing the data we have received in order to submit our

findings to a professional academic journal such as the Latin American Research Review

or Ethnomusicology.