Heidi Herrera and Faculty Mentor: Dr. Heather Belnap-Jensen, Art History and Curatorial Studies

Introduction

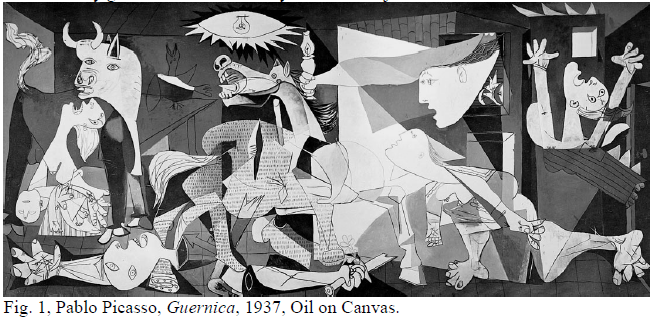

Although there is a wealth of scholarship on Picasso’s Guernica (1937) (Fig. 1), until recently

there has been a distinct lack of analyses completed through feminist methods, an approach

essential to a holistic understanding of Guernica. Conducting on-site research at the Museo

Reina Sofía in Madrid, I focused on the women of the painting, studying preparatory drawings

and works in which Picasso’s representation of women often borders on violent, painting them as

monstrous and agonized. The correlation between Picasso’s previous representations of women

and Guernica’s harrowing display of women and animals in pain participates within the Spanish

artistic tradition in which women have been used by artists such as Francisco Goya to show the

pain and horrors of war. The modern world’s tragic scene, Guernica, while reinforcing the

barbarity of modern warfare, participates in the androcentric artistic tradition in which the

consequences of war on the physical, psychological, and emotional well-being of women have

been systematically ignored in favor of using representations of suffering women as an artistic

device essential to ensuring the simultaneously empathetic and horrified responses of its viewers.

Methodology

Beginning my research, I compiled an annotated bibliography assessing key scholarship on the

painting, focusing on interpretations of the three women in the composition, studying how they

relate to the other artistic representations of women in the Spanish tradition and in the art of

Picasso. Due to the lack of scholarship which utilizes feminist theory, I employed a feminist

methodology in my assessment of Guernica’s preliminary sketches, similar works by the artists

and relevant writings.

Results

Iconographic interpretations of the piece offer little help and art historians have claimed the

women in the painting as either political and religious allegories or as personifications of the

women in Picasso’s personal life. In short, a survey of interpretations of the women in Guernica

reveals them to be representations of the political, personal, classical, allegorical, literary, and

religious. Indeed, these women might be representations of Spain, Picasso’s lovers, members of

a Greek Chorus, Truth or the Enlightenment herself, characters from the Numancia myth, or

Mary the mother of Christ. Any of these variations may be correct, and although many are

unlikely, this multitude of possibilities indicates a single truth; Guernica’s meaning is fluid and

has changed over time as its viewers have responded to the mural based on their own

understanding of artistic iconography and personal experience. Even Picasso was loathe to

ascribe a fixed symbolism to the painting, “It isn’t up to the painter to define the symbols. The

public who look at the picture must interpret the symbols as they understand them.”

Discussion

Beyond ascribing a specific symbolic meaning to the women in the tableau, I would like to

address the implications Picasso’s exploitation of women in Guernica through his stylization of

their pain, capitalizing on their suffering to elicit an emotional response from the viewer.

Comparing the mother lamenting her dead child, the deformed woman fleeing, the fragmented

woman screaming, and the light bearer catapulting out a flame engulfed window to Picasso’s

portrayal of male agony it is apparent that it is women’s responsibility to suffer. The placement

of the women of Guernica within the broken room, highlights that in this new form of warfare no

one is safe—even within the home, a sphere that in the past has “protected” women and children.

Their bodies have been transformed, mechanized as reflections of the bombs which have

wreaked destruction. Their breasts are deformed, indicating an absence of the maternal, replaced

by death brought by bombs. Their tongues and appendages have been weaponized, sharp and

dangerous to the gaze of the viewer. The monochromatic color palette prevents depth, pushing

the women forward, reiterating their suffering while simultaneously displacing the viewer,

preventing their integration within the space and thus distancing them from the suffering women.

By flattening the figures, Guernica becomes palatable to the audience of Picasso’s tragedy,

allows them to dwell on the images of these suffering women and feel if not compassion, pity.

The women of Guernica are incapable of transcending their predetermined role as victims.

Indeed, Picasso implicates the German bombers who terrorized a helpless civilian population,

while simultaneously ignoring his own culpability in creating the broken artistic space where he

demands women perform for his and his viewer’s catharsis. Picasso has attempted to craft

Guernica as our society’s modern tragedy, a spectacle of horror where women’s bodies have

become a vehicle by which Picasso demonstrates a universal suffering, playing God as he

commands his viewers to look upon his creation and be healed.

Conclusion

However, Picasso is participating in the androcentric artistic tradition which insists that women’s

role within war is often as a victim, aestheticizing and fixating on violence against women,

systematically ignoring that depicting this violence is in and of itself a form of violence. These

women are turned into beasts by their suffering, which functions to emphasize the bestiality of

the new warfare waged by the barbaric enemy. We cannot ignore the way Picasso discussed the

women he painted. As recorded by Françoise Gilot in 1950, “I want to underline the anguish of

the flesh… Like any artist, I am primarily the painter of woman, and, for me, woman is

essentially a machine for suffering.” We cannot reinterpret his words, attempting to paint him

and his representations of women in a better light in an attempt to frame Picasso as a

revolutionary genius within the history of art. He is just a man.