Erin Modersitzki and Dr. Christopher Oscarson, Comparative Arts and Letters

Introduction

The understanding of art and literature depends on an ability to contextualize it within the discourses from which it emerges. This project combined two important new strands of literary research to flesh out the context in which the idea of ecology emerged in Sweden: digital humanities and ecocriticism. We used digital tools to complement traditional literary approaches, broadening our understanding of even non-literary texts by suggesting patterns and constellations of ideas that elude any individual reader attempting to read and analyze hundreds of thousands of pages of text. Proving the viability of these “distant reading” tools through test cases like this project help to establish the methodology and the usefulness of the approach for future research.

The goal of this project was to draw upon the tools and resources of the Nordic Digital Humanities Lab directed by Dr. Oscarson to analyze and develop a new understanding of the emergence of the idea of ecology in turn-of-the-century Swedish thought, and most particularly in the articles from approximately 50 years of key popular scientific journals from the period. The topic of interest for this project concerns timely questions regarding the human relationship to physical environments. How those questions are answered are important for how humans act, how nature is conceived, and what nature means that are critical to understand in an age of environmental degradation and crisis.

Methodology

To complete this project, we utilized the BYU Nordic Digital Humanities Lab (nordicdh.org) to apply analytic methods to the annual publication of the Swedish Tourist Association (STF) as well as the annual publication from first Swedish nature conservation society (SNF). We were interested in creating topic models of the STF journal (1885-1935) and the SNF journal (1910-1935). The first step was to find and upload the journals into our digital library. After receiving the texts, we were then tasked with uploading the files digitally and transforming them into readable, coherent articles. Once these articles were deemed appropriate, we ran them through a script to create the first “draft” of word groups used to topic model.

To test the coherence of our results we were required to tweak the parameters of the modeling and constantly compare it over and against the original text. Ideally, we wanted to see coherent topics emerging in order to isolate those topics that seem most promising. Our focus for these topic models was the specific questions we are interested in regarding the representation of the human relationship to nature. We used close reading skills to analyze individual passages where the topics are most clearly manifest. We also ran the texts through the script several times as we refined our process and learned what kinds of words carried literary significance.

Results

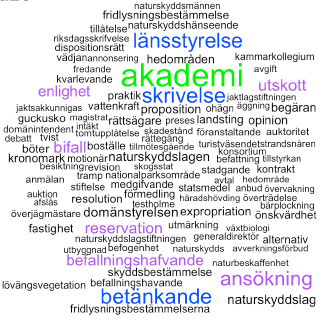

We were able to generate word clouds and topics from the SNF and STF journals, but the process took much longer than expected. We chose not to name the topic models, as we feel the texts and stop words (i.e., words that have no literary significance that we tell the script to ignore) need to be refined to create a more general sense of the ecocriticism in Sweden during the time period. By next year, we should have clearer and more accurate topic models published on the website. However, despite our setbacks, we have proved the viability of digital humanities tools and are paving the way for future projects in the digital humanities.

Discussion

This project did not pan out on our projected timeline, but this seems to be an advantage for the future projects within the digital humanities lab. We ran into multiple problems with the texts, the software doing the analyzing, the stop words, and the word clouds being generated. However, we were able to work through the unexpected issues and still come out on top in the end, with new and significant knowledge about the workings and ‘backbone’ of digital humanities. I gained knowledge not only about literature through this project, but programming and coding as well, which was an unanticipated learning experience for me.

Because we are paving the way for digital humanities as the field rises in popularity, we were never exactly sure what we would get or how much effort it would take to get there. Our first roadblock was in preparation, where we had difficulty finding texts and refining them to be understandable and readable. We contacted many libraries and professors in the Scandinavian studies arena, both in the United States and across Europe, in order to find the texts. Through this, we were able to make new connections and strengthen old connections in order to find what we needed. This would not have been done without Dr. Oscarson, who worked tirelessly to retrieve the information we needed.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this project showed promising insight into the world of ecocriticism and digital humanities. We are still looking forward to finding the final results of this project, but we now have a better understanding of how to go about a digital humanities project. We have learned about the software and scripts used, and we feel more prepared to tackle a project of this sorts in the Swedish realm. We are the pioneers of digital humanities in different languages, and we are passionate about the results waiting to be found.

Figure 1 – An example of a word cloud created by our script using the texts from the STF and SNF journals. The larger the word, the more importance it carries in a word cloud. After analyzation, this group could be named Nature and Academia.