Rehtaeh Beers and Dr. Jay Goodliffe, Political Science Department

All-mail elections are rare within the United States of America. Currently, only Oregon, Washington, and Colorado use mail-in ballots. Alaska will join that list during the 2018 midterm election as they adopt an all-mail ballot mode of voting1. All-mail election ballots require no more effort than original registration; the ballot comes automatically and all one must do is complete it. Due to the increased convenience, increased turnout is expected among those voters who are already willing to register. Mail-in ballots are proven to be more cost-effective than traditional voting2, allowing for the replacement of millions of dollars’ worth of ballot boxes with scanners and printers. Most importantly, however, mail-in ballots may increase voter turnout. My research examines the effect of all-mail elections on voter turnout to determine if the all-mail ballot format increases the likelihood of citizens voting.

I analyzed the CCES Panel Study for 2010 through 2014 elections. The panel data presents a validated vote status for the individuals who were surveyed. Other data sets only show the intent to vote, or self-reported voting status. My concern with self-reported voting status is that citizens tend to over-report3 their vote. To avoid inaccuracy in my results due to over-reported voting, I decided to use the CCES panel survey. The CCES panel survey includes hundreds of variables on numerous subjects on the individual level, allowing for a well-controlled statistical model.

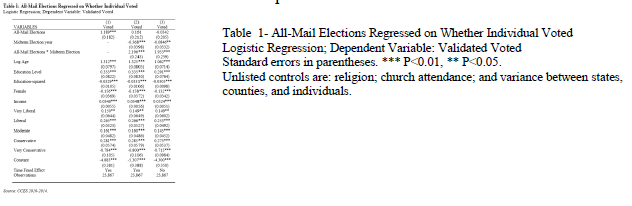

My primary method of analysis is a multilevel statistical logistic model. My models include the 2010, 2012, and 2014 elections years, regressing all-mail election periods and an interaction of mail-in ballots with midterm elections on the binary variable of a validated vote. The dependent variable is validated voter turnout, defined as whether an individual voted in the given election cycle.

It is important to control for the two separate types of elections—midterm and presidential elections—as they tend to have generally different turnout. Midterm elections, or any election held in a period when the president is not up for reelection, have a reputation for lower voter turnout. One possible reason for reduced turnout is that the amount of competition4 between parties is lower and campaign expenditures are generally reduced5. These findings and speculation on the reasons for reduced turnout during midterm elections recommend that citizens need encouragement to vote during midterm years because they have less information given to them about the election in the form of campaigning and mobilization efforts. Political events and campaigns serve as catalysts for decision making6 and opinion gathering.

My analysis implicates that all-mail elections do affect turnout. In Models 2 and 3 in Table 1, I look at the factor of the effect of midterm election years and its effect on voting turnout when all-mail elections are used. The relationship between midterm elections is expectedly significant on the probability of turnout in each election. Thus, I find that all-mail elections do not significantly increase the probability of an individual voting in presidential elections, but as common theory suggests, all-mail ballot elections do increase the probability of voting during midterm elections. In Model 3 I found an approximate 18 percentage point increase in the probability of an individual voting during the midterm election. This increase was muted during all-mail elections in Model 1.

It appears that the probability of an individual voting in a midterm election when there is an all-mail election is higher than if there is a normal in-person election style. I cannot be certain of the exact cause of this result, but it appears that it may pertain to increasing the convenience of voting during election years when the elections are not prominent media topics. It may be that receiving a ballot in the mail provides already-registered voters an extra push to do research and cast their votes. Doing further testing could enable us to determine if those who are already registered have a higher tendency to vote during midterms with all-mail elections as opposed to those registered in other states who do not have all-mail elections. If my theory is correct, this would show an increased turnout in those voters who are already willing to register.

To determine the exact effects of all-mail elections over time will require a significant amount of additional research. A better form of analysis to determine the true effect of all-mail elections of voter turnout would consist of collecting data over time from each state individually and analyzing each collection of data individually as time progresses. In other words, individualized voting records would be necessary along with some minor demographical information. There is a possibility that the effect of all-mail elections on increased turnout during midterm elections would decrease back to original levels, stabilize, or even continue to increase for a time. To determine these effects for states such as Washington, the turnout in the state needs to be followed over time for a more extended period.

Works Cited

- Maxwell, Lauren. “Anchorage Assembly Members Approve Vote-by-Mail Elections.” KTVA Alaska. 23 March 2016. Accessed 12/12/2016. http://www.ktva.com/anchorage-assembly-members-approve-vote-by-mail-elections-975/

- Hamilton, Randy. 1988. “American All-Mail Balloting: A Decade’s Experience.” Public Administration Review 48, (5): 860-866.

- Bernstein, Robert, Anita Chadha, and Robert Montjoy. 2001. “Overreporting Voting: Why it Happens and Why it Matters.” Public Opinion Quarterly 65, (1): 22-44.

- Hinckley, Barbara. 1980. “The American Voter in Congressional Elections.” American Political Science Review 74:641-650.

- Dawson, Paul and James Zinser. 1976. “Political Finance and Participation in Congressional Elections.” Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 425:59-73.

- Sears, David O. and Nicholas A. Valentino. 1997. “Politics Matters: Political Events as Catalysts for Pre-Adult Socialization.” American Political Science Review 91, (1): 45-65.