Sarah Curry and Dr. Christopher Karpowitz, Political Science Department

Political psychologists Jonathan Haidt, Jesse Graham, and Brian Nosek argue in their influential study that morality is not a “one-dimensional spectrum” with individuals being moral or amoral.1 Rather, moral foundations theory allows people to be explained across five dimensions: harm/care, fairness/reciprocity, ingroup/loyalty, authority/respect, and purity/sanctity. Individuals place varying emphasis across the five dimensions, which they use in making judgements about a situation’s morality. Graham et al. find compelling evidence that conservatives and liberals have different approaches to life and politics due to varying moral foundations. Conservatives usually place equal emphasis across the five dimensions., while liberals tend to value the “individualizing” dimensions of harm/care and fairness/reciprocity more than the other three “binding” dimensions.

While all five dimensions offer important insights, purity/sanctity tells a unique story. The dimension is based in the evolutionary psychology of disgust.2 In the development of human history, disgust allowed for survival when eating scavenged meat or being too near human waste could be deadly. Now an engrained human characteristic, these “behavioral immune systems” have led humans to view the body as corruptible and worthy of protecting. This understanding of disgust informed modern definitions of purity and degradation, including ideas of living an elevated, less carnal lifestyle that can be corrupted by immoral behaviors.3

The current measure for purity is intended to measure this noble, more elevated lifestyle, but essentially captures religious influence on moral determinations – an increasingly oversimplification of society. The measures include asking participants to evaluate the relevance of typical religious sentiments, such as God’s approval of behavior or whether chastity is an important virtue for teenagers. Utilizing these measures, it is not surprising that conservatives value the dimension more than liberals do, as conservatives tend to be more religious than liberals. While these measures of religious purity are crucial to understanding the deeply held beliefs of some, the measures miss a growing demand for purity among the unaffiliated. Importantly, in 2014, 28 percent of Democrats were unaffiliated with religion. This is an increase of 9 percent from 2007. If this trend continues, approximately a third of Democrats will be considered “secular.”4

The standard moral foundations questionnaire was used, replicating the original Graham et al. (2009) surveys. All participants took a questionnaire to determine the moral relevance of the dimensions in making moral judgements. They were asked to evaluate statements such as “whether or not someone was denied their rights” from never relevant to always relevant. Participants in the first condition received a second questionnaire which introduced contextualized moral judgements in situations that either affirm or violate the foundations that are thought to play an important role in moral decision making. Secular purity measures were added to both the moral relevance and moral judgements blocks. The second condition received a set of behavioral measures that gauged the influence of secular purity on various political and nonpolitical actions. The survey was taken by 697 individuals on Mechanical Turk from April 1- 3, 2017.

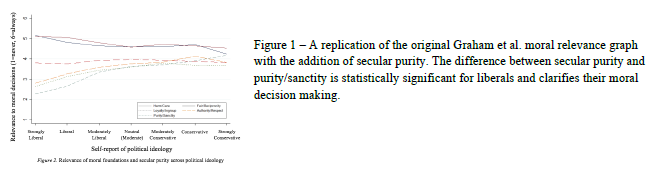

Initial factor analysis of the relevance measures reveal that the current purity items and the new secular purity items load together. This means that both measures are capturing the same general phenomenon – purity. However, rotating the factors allows for two distinct factors to appear. The secular purity items are indeed capturing something that the current purity measures are missing. In OLS regression, secular purity is a statistically significant predictor of liberal ideology, along with traditional predictors harm/care and fairness/reciprocity. The effect is approximately the same size as fairness/reciprocity and passes it when controls are added to the model. This suggests individuals who place a greater emphasis on secular purity are more likely to be liberal. While it may not make the difference between a strong conservative and strong liberal, emphasis on secular purity increases the probability of liberal political identity.

All in all, these results suggest that secular purity does exist and it can be used to predict liberal ideology under some conditions. The measures are not perfect, particularly in the moral judgments questionnaire. However, they are suggestive enough to warrant further research. From a methodological perspective, these results demonstrate that the current measures of purity are in fact exclusive. It suggests that political science would benefit from a more expansive version of purity; such a measure would enable a clearer understanding of the purity dimension in ideological development and moral decision-making, particularly among liberals. Researchers now have an opportunity to explore the full range of moral foundations theory and its implications on political attitudes and behavior.

Works Cited

- Graham, Jesse, Jonathan Haidt, and Brian A. Nosek. 2009. “Liberals and Conservatives Rely on Different Sets of Moral Foundations.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 96, no. 5: 1029-1046. PsycARTICLES, EBSCOhost. Accessed October 14, 2016.

- Graham, Jesse, Jonathan Haidt, Sena Koleva, Matt Motyl, Ravi Iyer, Sean P. Wojcik, Peter H. Ditto. 2013. “Moral Foundations Theory: The Pragmatic Validity of Moral Pluralism.” Advances in Experimental Social Psychology no. 47: 55-130.

- Ditto, Peter, Jesse Graham, Jonathan Haidt, Ravi Iyer, Sena (Spassena) Koleva, Matt Motyl, Gary Sherman, and Sean Wojcik. 2016. Accessed April 4, 2016. www.moralfoundations.org.

- Pew Research Center. 2015. “U.S. Public Becoming Less Religious.” Pew Forum, November 2015. Accessed February 15, 2017. http://www.pewforum.org/2015/11/03/u-s-public-becoming-less-religious/