Soren Schmidt and Dr. Michael Barber, Political Science Department

Introduction

Do voters prioritize party loyalty or personal ideology when casting a ballot? In the contemporary political climate, it is nearly impossible to tell because the two go hand in hand: almost all Democratic candidates are liberal, and almost all Republican candidates are conservative. Consequently, it is difficult to discern, for example, whether a voter supports a Democrat because the candidate is a Democrat, or because the candidate is a liberal. However, Utah’s 2016 presidential election presented a highly unusual opportunity to separate the two factors. In a state consistently dominated by the Republican Party, the collision of a highly unpopular Republican nominee (Donald Trump) and an appealing independent candidate (Evan McMullin), together with the other available options, was a chance to bring into sharp relief the relative strength of partisanship and ideology in determining vote choice. Studying the election’s results sheds new light on party defection and its motivators.

Methodology

Data from the 2016 Utah Exit Poll, a scientifically administered survey conducted on voters throughout Utah, provided us with the information we need to discover the strength of the various voter considerations. In addition to basic demographic questions, the survey also asked about ideology, religiosity, minority status, and many other factors that could potentially play a role in decisions about who to support on Election Day. Using this data, we perform multinomial logit regression analyses that isolate the independent effects of each of those characteristics and preferences.

Our dependent variable is the choice of the four main options available to voters: Trump, Clinton, McMullin, or someone else. Our independent variables are the possible motivators of vote choice that have been outlined above, controlled by demographic and other basic characteristics. This analysis will show us how strong the pull of partisanship truly is when brought into conflict with other preferences, thereby illuminating the conditions under which party defection is most likely. The results have implications not only for Utah, but also for any electorate that faces such candidate dilemmas in the future.

Results

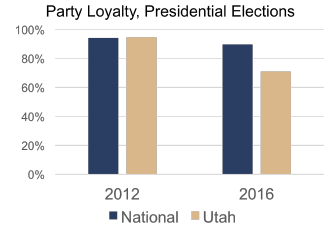

As displayed in the figure to the right, Utah’s 2016 election had an enormous jump in party defection. In 2012, Utah’s party loyalty (95 percent) was actually slightly higher than the national average (94 percent). But in 2016, Utah’s party loyalty was only 71 percent, much lower than the national average of 90 percent. This suggests that McMullin’s presence in the race made a significant impact.

So, which Utah voters defected from their party in 2016? In general, voters who were female, highly educated, and not unemployed (either working full-time, homemaking, or retired) were more likely to defect from their party vote. Notably, active Republican (and even some Democrat) members of the LDS Church were especially likely to defect and vote for McMullin, a member of the LDS Church.

In regards to our main independent variables of interest, the results are largely what we would expect. Republicans were far more likely than Democrats to defect to McMullin, and the voters who self-identified as “Moderately conservative” were the most likely to defect to McMullin regardless of their party affiliation. Notably, “Strongly conservative” Republicans were less likely to defect than their “Moderately conservative” counterparts.

Moreover, we find that the magnitude of the impact of party identification on defection is about the same as that of party identification. The difference in defection rates between the two parties is about 20 percentage points, and the difference in defection rates between a very liberal and very conservative personal ideology is also about 20 percentage points.

Discussion

One of the most salient takeaways from this research is that party identity and personal ideology remain highly correlated in vote choice. This research finds that correlation to be largely robust even in a scenario (such as Utah in 2016) in which some voters are faced with a relatively clear dichotomy between party and ideology.

For Utah Republicans, the group whose choice in 2016 best fit that description, we find an interesting and unexpected result in the lower defection rates of “Strongly conservative” voters than those of “Moderately conservative” voters. In theory, the strongly conservative voters would feel even more compelled by their ideological distance from Trump—and proximity to McMullin—to defect. There are at least two possible explanations for this phenomenon.

The first is that very conservative voters were simply acting strategically: knowing that McMullin had little chance of winning the Presidency, and believing that the margin of victory between Trump and Clinton could be quite narrow, they hedged their bets by voting for Trump, who was not as conservative as McMullin, but more conservative than Clinton. Additional qualitative research—asking strong conservatives why they voted as they did—could reveal whether this actually happened.

An alternative explanation is that respondents in the Exit Poll survey conflated the terms “conservative” and “Republican.” This confusion is quite common, and could have resulted in respondents indicating that they were strong conservatives when in fact they meant that they were strong Republicans. This would explain their lower levels of defection. One way to discover whether this happened would be to create an ideology index for each respondent, based on their answers to policy questions, that could estimate whether they were truly as conservative as they indicated or simply more loyal to the party.

Conclusion

Understanding who defects from their party—and why—is a critical foundation of political science. The choices that voters make, based on their beliefs about parties and principles, are the most fundamental building blocks of democracy. Utah’s 2016 Presidential election provided new insight to this field.

This research indicates that while unique circumstances can produce noticeable alterations in voting choices, party identification and personal ideology remain both highly influential and highly correlated when voters go to the ballot box. Interestingly, we find that the more conservative Republicans (and members of other parties) are, the less loyal they are to their party, except for those who rate themselves as “strongly conservative”—they are actually slightly more loyal than moderate conservatives.

Additionally, this research has raised new questions that merit additional study. For example, to what degree are voters motivated by strategic voting concerns when faced the temptation to defect from their party for a candidate who is more ideologically proximate? And are self-reported measure of party identification and personal ideology inaccurate because survey respondents conflate the two measures? These questions provide fertile ground for future research.